Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#50 – #41)

Time seems to be really good at sneaking up on people, and for a lot of us here at Way Too Indie it was hard to believe that our little site has been running for five years (Happy Anniversary to us!). We weren’t sure on what the best way to celebrate our anniversary month could be, but then it suddenly hit us: Way Too Indie’s 5th anniversary just so happens to fall on the halfway point of the decade.

So we spent most of the last 2 months putting together our collective list of the best 50 films of the decade so far. After a lot of deliberating and discussing, we compiled this list of 50 films that came out between 2010 and 2014 (Note: we went by original release date, not US, meaning some films like Dogtooth and A Prophet couldn’t make the cut). These are the films we love, cherish, and will remember years and years from now. A lot has changed with film in the last 5 years, but the quality of the creative output only seems to keep getting better. Here’s to an amazing first half of the decade, and let’s hope the next five years lead to even bigger and better things.

Each day this week we will reveal ten films from our list of 50, so check back tomorrow for the next group of films.

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far

(#50 – #41)

Argo

This 2012 political thriller won Ben Affleck the Oscar for Best Picture but that wouldn’t have guaranteed it a spot on this list. What really put it over the edge were a number of factors including the combined talents of Bryan Cranston, Alan Arkin, and John Goodman. My favorite moments of the movie were all of the ones with them in it. Though Argo has been criticized for taking some all too common Hollywood liberties with the truth, such as minimizing the role of the Canadian Embassy in the rescue, it’s success in revisiting a moment in our history whose details had only been made known to the public when the classified documents were published in 1997 made it a film worthy of note and attention for it’s portrayal of CIA exfiltration specialist Tony Mendez’s unconventional attempt to rescue members of the US Embassy in Iran taken hostage during the revolution. [Scarlet]

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Beasts of the Southern Wild’s biggest achievement is its ability to create a world that is both fantastical and grimly realistic. Benh Zeitlin’s Hurricane Katrina parable plays as a fantasy, but doesn’t wash away the serious realities facing the people in this environment. Enhancing the world-building is the community of actors (in many cases, non-actors) who feel authentic but are never looked down on. Honestly, I have nothing in common with these characters and don’t have any contact with the real-life versions of them, but I’m able to live in this world for 90 minutes. This community is strong, happy, unwilling to be changed or catered to. Some have complained that this approach feels like a grotesque travelogue for privileged outsiders to connect with the less fortunate, but I think that is a grave exaggeration. Perhaps I could see that a little more if there wasn’t as much soul in the work. Beside its wonderful magical realism, Beasts of the Southern Wild is grounded in the relationship between Hush Puppy and Wink, with powerful performances from Quvenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry. [Aaron]

Toy Story 3

For all of its technological greatness, Pixar Animation’s first film, 1995’s Toy Story, was also a triumph in the story it told—a story embracing nostalgia (with ample pathos) and doing so without schmaltz or contrivance. After A Bug’s Life came 1999’s Toy Story 2, which is remarkable as both a glorious stand-alone tale (this time about commodifying nostalgia) and one of those rare better-than-the-original sequels. The studio’s next seven films would offer an embarrassment of creative and original riches: Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Cars, Ratatouille, WALL-E, and Up. But for their 11th film, the studio knew it had one more great tale to tell from the toy box, and Toy Story 3 turned out to be the best of the trilogy, continuing its path down nostalgia lane to…the lane’s end. It’s heartbreaking farewell to nostalgia—a farewell born of something as normal and natural as growing up, summoned forth the heaviest of tears in a collection of films rich with Kleenex-demanding moments. There’s now a Toy Story 4 in the works, and while my knee-jerk reaction is to scoff at the notion of another sequel, Pixar’s handling of Woody, Buzz, and friends has not let me down yet; in fact, it has only ever lifted me up. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have something in my eye. [Michael]

Winter’s Bone

Debra Granik had only directed one other film when her indie Winter’s Bone came out. Starring the yet-to-be national treasure Jennifer Lawrence, then relatively unknown, the film was a sleeper. The kind that had a general buzz, though no real commercial success, following its Sundance premiere and a Grand Jury Prize win. After all, a backcountry noir taking place in the bluish bleak Ozarks following a teenager looking for her missing father among her rather sinister meth-making family, was never going to be the family-fun hit of the summer. And while we’re grateful for this film catapulting J-Law into the serious film world (and earning a first Oscar nomination), what makes Winter’s Bone deserving of this list is that Granik created an enthralling mystery propelled by the immense talent of all its performers (though, definite shout out to John Hawkes and all his cigarette smoking). Up until its last shocking moments the film captivates. Most especially by Lawrence’s Ree Dolly, a feminist heroine holding her own among bumpkins, addicts, liars, and her own evil family. Watching a man endure what she faces would surely not have been as compelling. Winter’s Bone is a film of strength and artistry, a time-tested combination. [Ananda]

Leviathan

Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab (official site) has been home to some seriously innovative and aesthetically astute moving images since 2007. It wasn’t until 2012, however, that whispers of this wondrous Lab began to resonate wider in the film world, when Lucien Castaing-Taylor (director of SEL, and professor of Visual Arts and Anthropology at Harvard) and Véréna Paravel got together and created something wholly extraterrestrial in feel. Leviathan is a documentary (though that term is used very loosely when labeling anything that comes out of SEL) that follows a fishing trawler in the dead of night, as it goes about its unceremonious business. With freewheeling cameras strapped to the boat, at times operated by fishermen, or seemingly capsized on the murky surface of the ocean, Leviathan tethers the audience to the experience of industrial fishing, and to the beasts and humans who all play a role in the cruel theatre of unrestrained nature. It’s a viewing experience unlike any other of the decade so far, and is the furthest one could get from conventional, mainstream, filmmaking. Unforgettable, transportive, and frantically cinematic, Leviathan breathes through celluloid, drowning our senses in saltwater and the glory of filmmaking. [Nik]

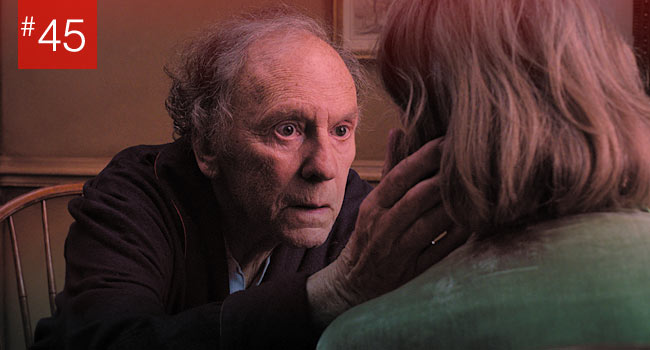

Amour

Michael Haneke’s Amour might be a slow-burner, but it packs one hell of a mean emotional punch. The film features two brilliant performances from Emmanuelle Riva and Jean-Louis Trintignant, who play an elderly couple madly in love with each other. The film defines what true love means, especially after the wife suffers from multiple strokes and the husband attends to her without feeling an ounce of burden. Haneke gambles by heavily implying how this will end from the opening scene, but his masterful presentation in this gorgeous foreign saga is anything but a wager. This may be Haneke’s most accessible film to date, earning the auteur the first Oscar nominations of his career. Amour is an emotionally charged love story that’s both inspirational and devastating, and if by the end you haven’t teared up at least once, you are a robot. [Dustin]

Oslo, August 31st

Joachim Trier’s Oslo, August 31st, while not at the top of this list, is certainly one of the most devastating films of the last five years. Taking place over a day in Oslo, the film follows Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie), a 34-year-old recovering addict trying to start his life over. Anders constantly teeters right on the edge of relapse, but the things driving him back to taking drugs are the sorts of universal issues films rarely address with this much potency. It’s about trying to move on from your mistakes when everything around you serves as a reminder of your past. It’s about seeing everyone you know leaving you behind as they figure their own lives out. It’s about spending every waking minute thinking about any life but your own. Oslo, August 31st is a film about failure, and one of the only films to deal with this topic in such a nuanced, sympathetic and realistic manner. [CJ]

Stray Dogs

Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs is a cavernous picture about a family scraping through the world inch by inch, tearing themselves to the bone. Lee Kang-sheng plays a homeless man who feeds his two children by holding up advertisement placards at a busy intersection all day, rain or shine (and boy do we see it rain). He and his kids squat in a dank abandoned building by night, bathe in public restrooms, and are forced to scrounge for their dinner. There’s a woman involved, too, but it’s not clear who she is, exactly. Is she the mother? A guardian angel? What makes things even murkier is that she’s played by three separate actresses. Ming-liang has a proclivity for insanely long takes, ten minute-plus static shots that achieve a level of intimacy only found in the corner of cinema he’s dug out for himself. Stray Dogs has a few of them, and they’re astonishing (especially the film’s final shot, which crushes the heart harder with each passing second). What’s remarkable about the film is that it forces you to take a long, hard, unblinking look at the nightmare of abject poverty, an issue we’ve all been conditioned to walk away from. It’s a devastating experience, and a stunningly beautiful one, too. [Bernard]

The Babadook

Good horror movies scare you with the unreal. Great horror movies terrify with the real. Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook does both. The writer/director sets us up and wears us out with a very real, first-half study of a mother’s descent into parental madness. Amelia (Essie Davis) is a tired single mom with a thankless job, inconsiderate friends, a flatlined love life, and a hyper kid. She is also a woman whose husband was killed in a car accident six years prior while en route to deliver that kid, leaving an ever-present—and always discomforting—sense of resentment that a mother should never feel towards her child. And that child is a handful—always at full volume and always full speed, ranting and raving and railing against a monster that doesn’t exist. Yet. Then the unreal occurs and the monster manifests itself from one of the simplest joys of childhood and one of the great mother/child relationship conduits: a children’s book. No sooner does Amelia wither from tired to exhausted, she must dig deep to find indefatigable to save her son and herself. [Michael]

Moneyball

It’s rare for a sports drama to discover untouched terrain within its genre. Story after story following ragtag bunches forming bonds to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles have played out so often in movies that the entire sports genre is often discarded sight unseen. Moneyball proves the exception to this unstated rule by largely moving the action away from the baseball diamond and into the executive conference rooms. Tracking often-derided Oakland Athletics’ general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) at the forefront of a burgeoning sports analytics movement, the sharp dialog in Aaron Sorkin’s script communicates the intricacies of “Moneyball” without becoming lost in a haze of batting percentages or average WAR scores. Moneyball makes the story of a sports executive engaging by illustrating the relationship dynamics Beane navigates between himself and members of his organization, as well as executives outside of the Oakland A’s. Seeing Beane negotiate, and attempt to influence the sports culture within his club makes a mostly unnoticed aspect of team sports appear just as vital as it is fascinating in the film. [Zachary]

See the rest of our Best Movies Of The Decade lists!

View Other Lists of this Feature:

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#40 – #31)

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#30 – #21)

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#20 – #11)

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#10 – #1)