Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#10 – #1)

All week long we’ve slowly been revealing our choices for Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far, and today we’ve reached the top of the list. While every film we’ve chosen thus far represents the incredible cinematic achievements made during the first half of this decade, the following ten films are the best of the best. Here’s to an amazing first five years of the decade, and hoping the next five lead to even bigger and better things.

Next week we will release our Best 50 Songs of the Decade So Far and later this month we will feature Best Albums and Best Television Shows!

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far

(#10 – #1)

The Act of Killing

The perspective Joshua Oppenheimer presents to his audience in his landmark documentary The Act of Killing is simply extraordinary. The most fitting comparison might be when horror movies in the 1980’s started using forced perspective shots from the killer. But The Act of Killing is about real life—and the genocide that spread through Indonesia in the mid 1960’s is far from the events of Camp Crystal Lake. The Act of Killing primarily does two things. First, it describes the Indonesian murders the gangsters committed in almost meticulous detail. Oppenheimer gives Anwar Congo and the other executioners the stage (quite literally) to create a historical record of what they did and how they did it. In doing so, the film becomes a deep and surprising character study of these men, who may easily be described as real life monsters. The boldest result of the documentary’s format, however, is how it forces these men to reflect on themselves—what was probably described to them as a showcase of their personalities, perhaps even as a way to show the world who they really are, instead forces the subjects to return to their crimes and reconsider them. This “act” is probably something Congo has done a million times in braggadocious retellings to friends and enemies, but there is something in the reenactment that incites a break in his character. The Act of Killing is quite disturbing, but also incredibly cathartic. [Aaron]

Blue is the Warmest Color

This film sent ripples around the festival circuit pretty quickly, and if you’ve seen it, it isn’t hard to see why. It has been described in a variety of ways, from “coming out narrative” to “bildungsroman,” and undoubtedly has provoked plenty of discussion around its sex scenes alone. But Blue is the Warmest Color does not fit into any one of the many labels it recalls, because it is not one movie. It is as easily placed into a genre as one can place the life of a woman into a genre. Because that is exactly what this film is: a life, a narrative that has more emotional reality than plot, and more symbolic function than events. To describe it in a summary of plot events does it little justice, because said events bear the relative significance of a wall to a house: indispensable, undoubtedly, but not anywhere near the defining feature. For one film to tackle love, art, literature, culture, class, education and above all, consumption, is ambitious enough, but to do so while seamlessly jumping a few years in time, and then leave us wanting more at the end of nearly three hours? That is truly remarkable. [Pavi]

The Turin Horse

Béla Tarr’s self-declared final film The Turin Horse is, if nothing else, a perfect ending to an amazing career. Tarr has defined himself for his use of long, elaborate takes, shooting long films in as few shots as possible. The most extreme example of this would be his 430-minute epic Satantango, which only contains about 150 shots. The Turin Horse runs at a considerably smaller length of 150 minutes, and only in 30 shots, but it can be a grueling experience. Taking place over six days, the film follows a farmer and his daughter as they live out an existence that almost amounts to nothing. Tarr spends over an hour of his film watching them go through the exact same daily motions, before slowly removing one aspect after another from their lives. First their horse won’t move, then the well dries, and by the sixth day things take an apocalyptic turn. The Turin Horse doesn’t exactly sound like a fun time, but its power is immense. Tarr has a style that’s all his own, and his work behind the camera (along with regular cinematographer Fred Keleman) is nothing short of extraordinary. There are plenty of grim films, but few can pull off the all-encompassing and evocative world Tarr creates here. The Turin Horse isn’t a pleasant experience, but it’s one that’s well worth taking. [CJ]

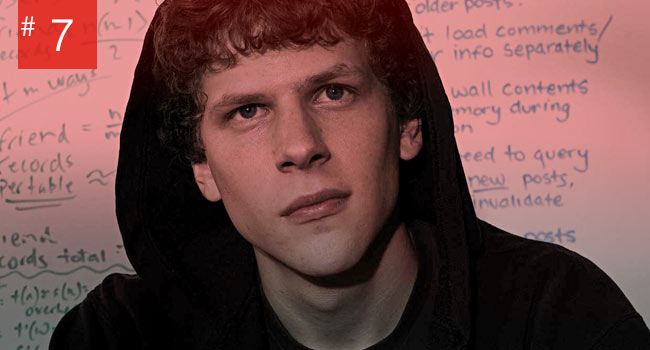

The Social Network

Let’s talk about unlikely masterpieces. “The Facebook Movie” interwove three timelines, two litigations, a hard-to-like protagonist, and the deterioration of his relationships, both personal & professional, into a story that more closely resembles Citizen Kane than other social media-based projects like Catfish or Unfriended. This coming from a filmmaker whose most iconic film works depict a serial killer who bases his murders on biblical sins and on an underground group of brawling men. Like most of David Fincher’s films, part of what makes The Social Network so distinctive is that it features his collaborators operating at peak ability. The movie features Jesse Eisenberg’s only truly transcendent performance, one that turns his neurosis into focused passive aggression. Both Andrew Garfield and Justin Timberlake are stellar here as well. Aaron Sorkin’s script tosses around computer programming jargon with the elegance of a ‘30s screwball comedy. The Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross score, their first contribution to Fincher’s films in what has since become a partnership, is likely the best of their collaborations to date with “In Motion” still a standout among the many great tracks they’ve produced. The Social Network captures the qualities of ambition and selfishness innate in the origins of wildly successful people, with an engrossing, modern aesthetic. [Zach]

12 Years a Slave

Steve McQueen’s unflinching depiction of slavery in the mid-19th century is the type of harrowing portrayal of true-life tragedy that rarely emerges from American cinema (perhaps explaining why this picture came from a British director). A thoughtful, focused look at an ugly but historic American institution is stripped of the hero’s journey narrative forced on a majority of studio-made films. There are few moments of triumph in 12 Years a Slave, barely any speechifying, and thankfully a notable lack of angelic, white savior figures to save Solomon Northrup. Instead McQueen implements his signature long takes to become a fly on the wall to the truly awful treatment that slaves received. Scenes involving the brutality of slave owners unfold in real-time, and without allowing the audience the benefit of a cutaway to more pleasant scenes. None of the movie should feel like a revelation to anyone with knowledge of America’s tainted past; however, the no frills honesty with which McQueen approaches his subject seems the only proper approach to this sad era of history. Complimented by stellar performances from Chiwetel Ejiofor, Lupita Nyong’o, Sarah Paulson and a terrifying Michael Fassbender, 12 Years a Slave is the type of film tragedy deserves, an unwavering representation of both the power of the human spirit and the evils of which humans are capable. [Zach]

Under the Skin

These days, science fiction seems to be all about the big budget FX. Recent sci-fi offerings ranging from the cerebral Interstellar to the MCU’s Guardians of the Galaxy all rely on huge FX set-pieces to sell their sizzle to the audience. It wasn’t always this way. In fact, one of the greatest, yet simplest, sci-fi entries of all time wasn’t even a movie—it was a radio show. Performed by Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater on the Air players in 1938, The War of the Worlds, adapted from the H.G. Wells novel of the same title, proves in retrospect that all the digital cinematic wizardry in the world can’t trump the powerful simplicity of a solid story and terrific performances. The same can be said about Jonathan Glazer’s 2013 film Under the Skin. Sure, it has some dazzling FX, but it’s the simplicity of story—a mysterious woman of otherworldly origins assumes the characteristics of another girl and methodically hunts men in Scotland—and a career-defining performance from Johansson (which is saying something), that makes the film not only mesmerizing, but an entry worthy of mentioning in the same breath as The War of the Worlds. It might be disguised as an art house film, but have no illusions, Under the Skin is a seminal entry in the sci-fi genre, setting a new standard of excellence and positioning itself to be the topic of discussion for decades to come. [Michael]

Nightcrawler

There are antiheroes, there are villains, there are sociopaths, and then there is Lou Bloom. Jake Gyllenhaal as the emaciated and determinedly self-assured young Bloom is more intricate than the average villainous protagonist. I’m not sure he can even be described as a sociopath because his motivations in becoming a scumbag video journalist, capturing the gruesome aftermath of horrendous Los Angeles crimes and accidents late at night, is decidedly an emotional investment. An investment in his own shockingly self-absorbed and narcissistic ambitions. A sociopath has no sense of their wrong-doing, Bloom knows and has already decided his own need to excel takes precedence. As the film debut of Dan Gilroy, Nightcrawler is especially impressive. Each action-filled scene made darkly beautiful by Robert Elswit’s camerawork—and the pace steadily increasing as Bloom’s thirst for notoriety increase—the film portrays the seedy side of Los Angeles and insightfully proves the darkest capabilities of humanity don’t always lie with the guy holding the gun. With exceptional work from Renee Russo—who proves she can shine when given the chance—as well as Bill Paxton and Riz Ahmed as Bloom’s unfortunate protege, the film is unsettling and yet guiltily fun. After all any sociopath or villain is only as compelling as how well they provoke us to consider how far our own ambitions could take us. Gyllenhaal’s Bloom sets a new bar for controlled crazy. But its exactly that control that makes this film so amazing and unsettling. [Ananda]

Her

Quite a turn from Spike Jonze’s last feature film in 2011, Where the Wild Things Are, which he also produced and directed, 2013’s Her was a necessary science-fictional exploration into a concern that has been discussed to no end since the introduction of the handheld mobile device. What would it lead to? Where could it take us? Jonze had already touched on those questions with his 2010 short I’m Here, but was able to delve a lot deeper with a feature film and a larger budget; and with the invention of Siri in 2011, the discussion became even more pronounced and more imaginative. Artificial Intelligence isn’t a new concept by any means in the world of science fiction, however this one tends to hit close to home. When one can barely go out in a crowd without most of the faces in it being buried in their phones, it doesn’t seem quite as far fetched as it used to be portrayed. We are already exceedingly further dependent on our devices than anyone is truly comfortable with. Spike Jonze capitalizes on that concern without actually getting preachy or sinister, while at the same time opening a window into the possibilities and allowing us to draw our own conclusions and moral stances on the subject. The response to the movie was hugely positive and it was considered a strong contender for the Best Picture category at the Oscars. It didn’t win but it did win an Academy Award and a Golden Globe for Best Original Screenplay. With an original score composed by Arcade Fire, it was also considered for an Oscar for Best Original Score and Best Original Song. Joaquin Pheonix is left alone to create most of the dramatic tension, emotional conflict, and plot-furthering entirely on his own physically-speaking, an incredible accomplishment. Although he was overlooked for an Oscar nomination, he was nominated for a Golden Globe for his performance. This futuristic love story holds just enough logic to be thought provoking, and its charming portrayal of a future society that seems only a few steps removed from our own makes for a mesmerizing watch. [Scarlet]

Boyhood

We’re constantly fighting time: we rush to work in a sweat, take medicine to extend our lives, agonize as we procrastinate instead of doing our taxes. Our war against time—the most unyielding, unstoppable thing in the universe—is a losing one, but with the advent of movies we discovered a way to cheat time, in a sense. With movies we can capture moments and relive them again and again, trick ourselves into thinking we’re someplace else, and even spend time with those who’ve long since left our world. It’s a wondrous thing. Richard Linklater’s Boyhood captures time in a most fascinating way, stuffing a sprawling 12-year story about a boy and his family into a 165-minute bottle of modest, elegant filmmaking. All movies help us cope with time in their own way, but what’s special about Boyhood is that it beautifully reminds us how lucky we are that we need not face life alone. The people who stand by us through all the ups and downs, through the little triumphs and the massive failures, through the mundane, ephemeral moments that fill up most of our days—they’re our greatest gift. Boyhood isn’t about extraordinary people. It’s about ordinary people who’ve shared lots of time together, and in doing so have found love in one another. It’s a film about family in the deepest sense of the word, and there have been few films over the past half-decade more worthy of your precious time. [Bernard]

The Tree of Life

It’s 2011, and the venerable Terrence Malick is set to make his Cannes debut with a new film. Six years passed since The New World, his last film, which was met with hushed response (though, many would later cozy up to it). So, nobody could really tell how The Tree of Life would play out. Aside from Malick, the flames of intrigue were stoked by the casting of Brad Pitt and Sean Penn, and rumblings of it being Malick’s most personal film to date. Fast track to 2015, and The Tree Of Life is a Palme D’Or winner, an important player in the year that turned out to be The Year Of Jessica Chastain (forget Pitt and Penn, though the former is outstanding here as well), and a gargantuan critical darling. Case in point: Sight & Sound released their updated Greatest Films Poll (updated once every 12 years) in 2012, and The Tree Of Life was just shy of cracking the Top 100.

All of this makes complete sense to most of us here at Way Too Indie (it’s No. 1 on my personal list, too). Terrence Malick has found a way to tap into the wonders of the human experience unlike any other director in the decade so far. Malick’s vision, and his creative impulse to search for God in the details of this semi-autobiographical story of a remembered childhood, is perfectly partnered with Emmanuel Lubezki’s luminous cinematography. The result is a limitless exploration into the essence of what makes us who we are, what we take from our mothers (materialized in Chastain’s eternal mother) and fathers (materialized in Pitt’s mortal father), and where God fits into it all. Like Linklater’s quest for life’s defining moments in Boyhood, Malick’s quest is similar, but with him the end result is a much more solemn and incorporeal one. More than any other film of the century so far, The Tree Of Life expands the boundaries of the art to its furthest corners. [Nik]

See the rest of our Best Movies Of The Decade lists!

View Other Lists of this Feature:

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#50 – #41)

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#40 – #31)

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#30 – #21)

Best 50 Movies Of The Decade So Far (#20 – #11)