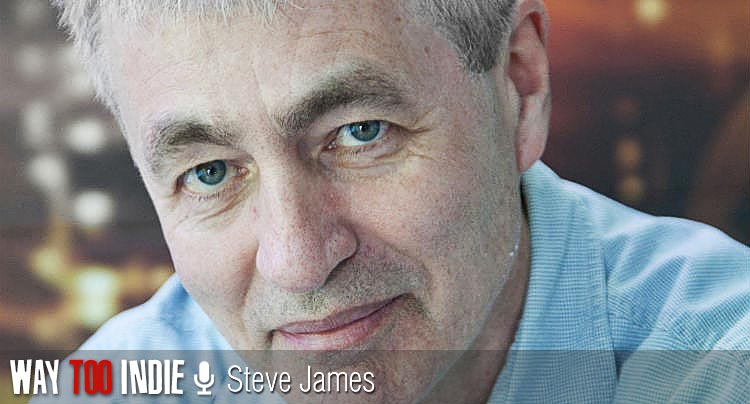

‘Life Itself’ Director Steve James Feels Lucky to Have Been With Roger in His Last Days

Timeless sports docu Hoop Dreams was famously one of Roger Ebert’s favorite films. It’s fitting, then, that its director, Steve James, is the man behind Life Itself, a stirring collection of memories from Roger and his loved ones woven together to give us one final, lasting memory of arguably the most influential film critic of all time. Tracing Roger’s life from his days as a young newspaper editor to his last days on earth, when he’d lost his ability to speak, the film pulls no punches, highlighting not just the beauty of the man’s life, but the conflict and suffering that emboldened his character.

James spoke with us recently about he and Roger avoiding the route of hagiography, using Roger’s memoir as a key reference throughout filming, voice actor Stephen Stanton, who portrays Roger in the film, he and Roger’s chilling final email exchange, and more.

The film is very funny at times, but there’s also often a lot of pain involved. This isn’t a hagiography. How important was that to you and Roger?

Steve: It was very important to both of us. Not that I expected to, but if I had read his memoir and felt, “I don’t really like this guy and I don’t respect him” I probably wouldn’t have made the movie. I’m not a filmmaker that would be interested in telling his story as some kind of exposé. At the same time, I wasn’t interested in telling his story as just a tribute. His memoir, being as candid as it was, was a good signal to me that he wasn’t interested in that either, and that certainly proved to be the case. Roger prized complexity, honesty, and intimacy in the films he loved, especially the documentaries. It’s something I’ve tried to do in my career, and this film is no exception.

Did you use Roger’s memoir for reference quite a bit during filming?

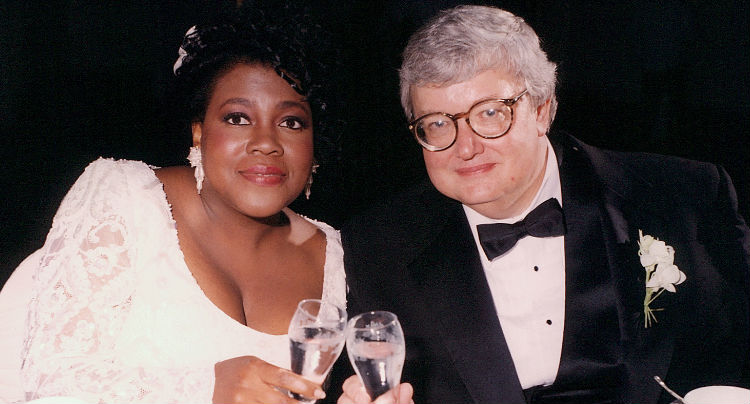

Steve: Absolutely. It’s based on the memoir, and for good reason. I thought it was a terrific piece of writing. The idea of basing it on the memoir made all the sense in the world to me, so it’s the primary text that serves the film. It serves the film in terms of content, of course, but it also serves it in terms of storytelling. In the book, he’s very much looking back on his life from the vantage point of the present when he’s been through a lot and he can no longer speak. By the end of the book, he’s anticipating death. When we started the film, we in no way thought that he wasn’t going to survive–that wasn’t the reason we made the film–but that’s what happened. The memoir is the key guiding text for the film, but we do deviate from it. One way is that, the film isn’t just Roger’s point of view of his life; it’s other people’s point of view as well. We also dig much deeper into the Siskel & Ebert show than he does in the memoir, because I think it’s such an important, key part of how we came to know Roger, how he was defined, and how he made an impact on film criticism.

There’s a Siskel & Ebert outtakes clip online that’s been one of my Youtube treasures for years now. It’s incredible footage, and I like the way you implement them in the film. You frame them with interviews that further illuminate the different colors and dynamics of their relationship over the years.

Steve: I’d seen those clips before, too. They weren’t original to the film, but I like to think that we give them a new context that made them resonate more deeply in terms of who these guys were, how they viewed each other, and the deep competitiveness they felt. But also, the second set of clips where you see them bonding over the fact that Gene’s a Jew and Roger’s Catholic…I found those illuminating as well. They showed that fundamental connection they made as well. It wasn’t all vitriol and conflict; there was a bond between them, too.

Stephen Stanton adds a lot to the film.

Steve: He added a whole other dimension of intimacy. One of the problems when we were putting the film together and showing it to colleagues was that we were using the CD version of the book for the editing. I always imagined we’d replace that with someone who sounded more like Roger, but it was very interesting when we showed it to people, because they would say, “I really wish it showed more of Roger’s writing.” I’d say, “There’s tons of Roger’s writing in the movie. All that stuff being read for the memoir is his writing!” When we found Stephen Stanton, this amazing voice actor who was able to impersonate Roger to the degree he did, it really helped to reinforce that these are Roger’s words.

It’s chilling at first to hear Stephen’s voice mimicking Roger’s, but after a while it all melts away and you forget it’s not Roger speaking.

Steve: That’s what I want. I want you to forget. You’d be amazed at how many people don’t even notice that it’s not Roger. I’m a documentary guy, so I didn’t want to fool people: At one point in the movie, “Roger” says, “When I lost my ability to speak…”. That flies right over people’s heads and they go, “That wasn’t Roger?” at the end of the film. I’m talking about critics, film lovers…Stephen so embodies Roger and they are his words, so it just flies by people, which I’m happy about, frankly.

There are points in the film where you superimpose text of Roger’s critique over the imagery of the film he’s criticizing. It’s a beautiful technique.

Steve: Thank you. I wanted to find a way to feature his criticism and also put it in the context of the films that had inspired such writing. I didn’t want to just have him speak the words; I wanted to put them on the screen so that you could admire the written words.

Have you spoken to Roger’s contemporaries about the film and how he impacted their lives and work?

Steve: I haven’t spoken to many of them directly, but if you read the reviews of the film so far, you’ll see that connection. Many of them write about it in some fashion in reviewing the movie. There’s something about Roger that compels people to want to share something personal about their connection to him. In terms of his contemporaries, critics might tell stories about him. But in the case of younger writers, they’ll talk about how he inspired them, either through his writing or the show. It’s remarkable how many people are moved to speak personally about him in reviewing the film.

Roger fully embraced the digital age late in life, and the film does this as well in many ways. You display several email exchanges between you and Roger on screen several times.

Steve: The decision to put my email exchanges in the film was one that was made in the wake of his death. The emailing was initially a very practical way to conduct an ongoing interview with him that we would then hope to record. The way Roger would do interviews in the years since he lost his ability to speak was, he’d ask for people to give him questions in advance so that he could type up answers. If you sat there filming and waited for him to type up an answer and play it back, it would take forever. It would be hard on him. When he died, the emails loomed way more important in the relationship between me and him and the storytelling. Our last series of exchanges where he’s clearly is declining and can’t bring himself to really respond was so poignant and distressing to me that I felt I needed to reflect that in the film.

You didn’t know it at the time, but you got to spend time with Ebert in his final days, which is such a privilege. What was it like being close to him the months leading up to his passing?

Steve: I felt very fortunate. I had a very friendly professional relationship with him over the years. He’d been very kind to me beyond what he did for Hoop Dreams in terms of my other films. I greatly appreciated that. But this was a chance to actually get to know him as a person. I feel lucky to have been with Roger in his last days.

Read our review of Life Itself, now in limited release in U.S. theaters.