Way Too Indie on ‘Company Man: The Films of Robert Altman’

Most directors would probably kill to have a career like Robert Altman’s. With a career spanning more than 4 decades, Altman proved himself to be one of the busiest, most creative and versatile directors in American history. He started out in the 50s working as a director for television, until his frustration over a lack of control prompted him to start working on feature films instead. It wasn’t until 1970 when his film career launched, thanks to the success of M*A*S*H. With a dozen features over the next decade, Altman established the traits of his unique style: overlapping dialogue, improvisation, large ensembles and the ability to subvert genre expectations.

Altman used to say he always saw himself as traveling in a straight line, and looking back at his career the statement couldn’t be more true. His output in the 70s only came from Hollywood studios because he was able to do what he wanted. The studios’ preference for blockbusters and bigger budgets at the end of the 70s, combined with the disastrous performance of Popeye, saw Altman turning his back on Hollywood, turning his attention to directing stage shows and filming play adaptations. Altman came back to Hollywood in the 90s in a big way with The Player and Short Cuts, and in 2001 he wowed audiences with Gosford Park, a film many consider to be among his finest works.

With Canadian filmmaker Ron Mann releasing his documentary Altman later this year, the TIFF Bell Lightbox is holding a retrospective on the filmmaker during the month of August. The retrospective kicked off recently with the Canadian premiere of Altman, and over the next 4 weeks the Lightbox will screen 18 films from the director. All of us here at Way Too Indie consider Robert Altman to be one of the true definitions of an independent filmmaker, so we delved into the line-up to give our thoughts. If you’re not familiar with the man’s films, please, do yourself a favour and check them out. The films in this line-up (they don’t even cover half of his output) would be a great place to start.

Company Man: The Films of Robert Altman starts on August 7th and ends August 31st at the TIFF Bell Lightbox. To find out more about the program, along with how to buy tickets, be sure to check out the TIFF Bell Lightbox Website.

M*A*S*H

Screens August 7

Altman’s breakout film is literally a national treasure, being one of three of his films chosen for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. It’s an honor thus far bestowed on less than 1000 movies. Watching this war satire today still feels disjointed, and yet significant. Altman’s use of segmented vignette-style filmmaking, with plenty of overlapping dialogue and a cast so large it is hard to keep track, can be an overwhelming viewer experience. But its effect is pronounced. The contrast between army surgeons in the Korean war, cracking jokes, chasing women, and downing martinis, and their bloody operating room coupled with the somber reality of death in battle, is one of the most effective filmmaking techniques used to depict the mental burden of war. Starring Donald Sutherland, Elliot Gould, Tom Skerritt, Robert Duvall, and a whole host of others supporting, the film is laugh out loud hilarious, with the darkest of humor. It is easily deserving of its 5 Academy Award nominations and a win for Best Adapted Screenplay, as well as its Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy). M*A*S*H had a tumultuous production, with the film’s leads doing their best to get Altman fired and not playing nicely with their detail-oriented director, but Altman’s discerning eye and auteur techniques jumped the hurdles of production, generating an instant classic and catapulting Altman’s film career. [Ananda]

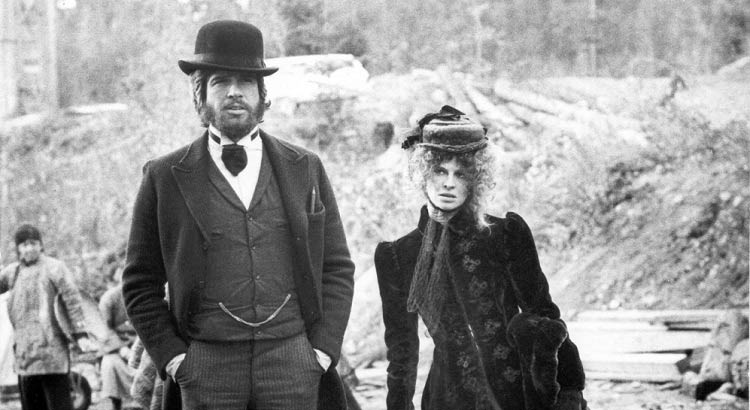

McCabe and Mrs. Miller

Screens August 8 (Note: Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond will be in attendance to introduce the film)

Altman’s take on the Western stars Warren Beatty as John McCabe, a gambler opening up a brothel in a small mining town. McCabe, a man with a reputation as a notorious gunman, meets his match with Constance Miller (Julie Christie, fantastic), a madam whom he must team up with to turn his business venture into something truly successful. The success of their brothel soon attracts the attention of corporate interests, and when McCabe refuses to accept their offers to buy the place up, the company sends bounty hunters to kill him instead. Altman’s dedication to realism works wonders here, and the subversion of Western tropes rightfully earned it the title of the “Anti-Western.” McCabe doesn’t fit the usual expectations of the Western hero, and Mrs. Miller constantly outsmarts her business partner without breaking a sweat. It’s these elements, combined with Vilmos Zsigmond’s excellent cinematography and a remarkable final act, that cement McCabe and Mrs. Miller as one of Altman’s best films. [C.J.]

That Cold Day in the Park

Screens August 9

Before Altman made M*A*S*H,he went off to Canada to make this low budget, independent thriller. A lonely woman (Sandy Dennis) living in her deceased mother’s apartment notices a young man (Michael Burns) sitting in the park outside her apartment in the pouring rain. She lets him into her place, giving him a bath and letting him stay the night while his clothes dry. He doesn’t speak a word, but the woman develops a twisted attraction to him, and it doesn’t take long before she makes sure he won’t ever leave her. The film, one of the more obscure ones in Altman’s filmography, definitely earns its reputation as one of his lesser works. It’s a mildly intriguing but ultimately boring film, one that feels more and more pointless as it goes along. Nevertheless, it shows Altman’s skill behind the camera whenever it ventures outside of the woman’s apartment, especially in one sequence when Dennis makes a trip to see her doctor. At the time Altman made That Cold Day in the Park, he was ready to move to Canada out of frustration at the Vietnam War; the only thing that stopped him from leaving Hollywood was an offer to direct M*A*S*H. The rest, as they say, is history. [C.J.]

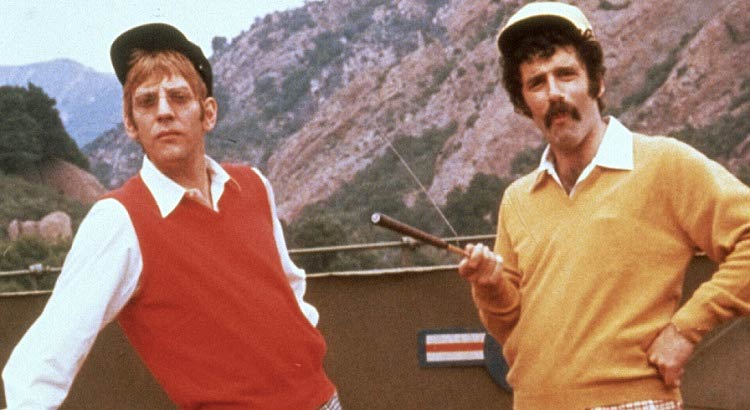

Brewster McCloud

Screens August 10

After the success of M*A*S*H, Altman took a wild left turn for his next film. Bud Cort stars as Brewster, a young man living underneath the Houston Astrodome building a machine that will give him the ability to fly. A mysterious woman (Sally Kellerman) acts as Brewster’s guardian angel, watching over him and ensuring no one puts a stop to his plans. There’s also a serial killer running around the town, and soon enough the lead detective (Michael Murphy) thinks Brewster is responsible. Altman reportedly despised Doran William Cannon’s screenplay, tossing it out and making things up as they went along, and it shows. Brewster McCloud is a truly baffling film, the kind of movie where trying to figure anything out is a waste of time. It’s also not very good. The ideas are wacky, but they’re rarely funny. It all amounts to a film that isn’t nearly as clever as it thinks it is. Brewster McCloud more or less vanished after it received a confused reaction from critics and audiences upon its release (it finally got a DVD release in 2010), but in recent years Altman fans have championed it as one of the more under appreciated films in his career. Clearly the film’s bizarre sense of humour appeals to some people, but from this writer’s perspective it’s easy to see why Brewster McCloud was shelved for so long. [C.J.]

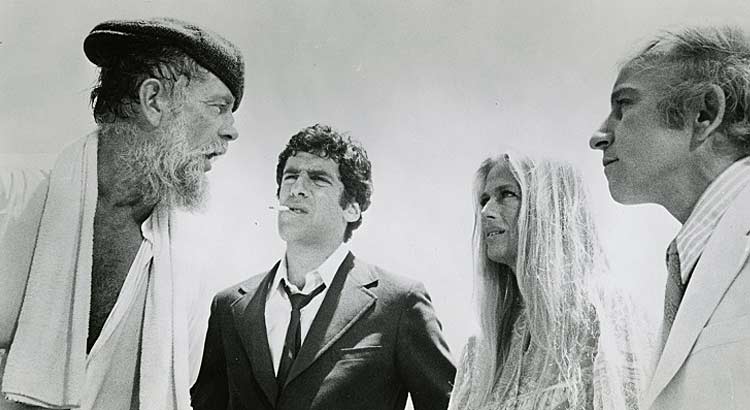

The Long Goodbye

Screens August 17

Adapted from the Raymond Chandler novel, and featuring the infamous, chain-smoking, wisecracking private eye Philip Marlowe, The Long Goodbye is one of Robert Altman’s greatest directorial achievements. Written by Leigh Brackett (who previously adapted another Chandler novel, The Big Sleep, for Howard Hawkes,) the film is centered on Marlowe’s friend Terry Lenox, who seeks Marlowe’s help to cross the border one night after having a fight with his wife. The next day, Marlowe is brought in for questioning and accused of abetting murder; Lenox’s wife was found dead, right after Terry’s visit to Marlowe. But Marlowe only spends a few nights in jail because Terry commits suicide in Mexico, and the case is closed. Except, of course, it’s not. A security guard impersonating celebrities, a goon assigned to follow Marlowe around, the alcoholic author Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden, in scintillating form), a sociopathic Jewish gangster played by director Mark Rydell, and the classic damsel in distress (Nina van Pallandt) are only a handful of colorful supporting players orbiting around the scraggly Marlowe, brought to life by the impetuous and charismatic Elliot Gould. Produced during Altman’s glorious 70s phase, The Long Goodbye is full of quotable dialogue, a haunting melancholic theme song, and scene composition combusting with vibrancy. Example? The camera panning and following Marlowe as he walks on a busy Mexican street, strikes a match on the ground, and continues on his way only for the camera to momentarily lose interest in him and zoom in on two dogs humping. One of the dogs breaks it off violently and we abruptly cut back to Marlowe. There’s another scene featuring a coke bottle, improvised by Altman himself, which I won’t get into here on account of its power to surprise. Suffice it to say, The Long Goodbye is no standard film noir, but one with Altman’s cinematic acumen stamped all over it, making it a timeless classic of the genre, somewhere up there on its own level. [Nik]

Thieves Like Us

Screens August 19

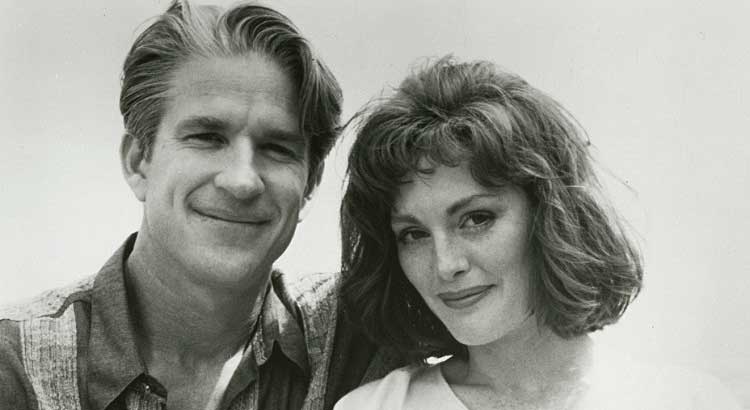

Thieves Like Us, Altman’s tenth feature film, tells the story of a group of bank robbers and murderers who become stowaways at the home of a Mississippi gas station attendant. The film features many elements of the director’s notable style, including a naturalistic environment and non-conformist themes. Thieves Like Us, though, is perhaps the key example of his overall style not totally clicking. The film has a carefree rambling quality that totally works against the sometimes violent plot, and surprisingly ends up as a slog. Unlike many Altman films, this focuses more on its two leads than a large ensemble. Fresh-faced Keith Carradine and Shelley Duvall both give strong performances as the young lovers. Carradine brings a strong balance of an innocent young man and cold-hearted criminal, making him a man you root for to leave his life of crime, even as he shows no interest in doing so. His scenes with Duvall as their love blossoms are the most enjoyable of the film, quiet and romantic. Perhaps the biggest sin of Thieves Like Us is its similarity to Bonnie and Clyde, which was released seven years earlier. The connections are easy to see with the outlaws-on-the-run plot, liberal sexuality and violence — Thieves Like Us even ends in a heavily stylized slow-mo shootout. You can’t see Thieves Like Us and not think of Arthur Penn’s game changing Hollywood film, a matchup that doesn’t end up favoring Altman. [Aaron]

Images

Screens August 19

Images screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1972, earning a Best Actress award for Susannah York. Later that year, it screened at the New York Film Festival, and one negative review in the Times convinced the studio to bury the film. It took 30 years before Images resurfaced on DVD, and it’s shocking that such a terrific film was kept hidden for so long. York stars as Cathryn, a children’s book author suffering from schizophrenia. Her husband takes her to the Irish countryside for a vacation, and her hallucinations only seem to get worse. Altman makes two interesting choices here: the film is completely subjective, as everything is seen through Cathryn’s point of view, and it’s completely aware of her illness. Cathryn constantly finds her husband switching bodies with other men, and Altman lets these scenes linger for so long it’s impossible to tell where Cathryn’s hallucinations end and reality begins. It’s an amazing mind-bender of a film, with plenty of gorgeously haunting imagery from cinematographer Vilmos Szigmond, and an unsettling experimental score by John Williams & Stomu Yamashita. Horror fans & Altman devotees who haven’t seen Images need to see it immediately. Hopefully one day it’ll earn its rightful place as one of the best horror films of the 70s. [C.J.]

California Split

Screens August 21

The 70s were awesome for Robert Altman. It seems like he had the reputation of being a difficult director even before the success of his breakout film M*A*S*H in 1970, but, with support from a handful of chief critics like Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael, Altman ushered in a new, energetic, and unique American voice folks wanted to hear. He directed 13 films in this decade alone. Booming right alongside Altman was Steven Spielberg, who was toying with the idea of directing a script by Joseph Walsh called California Split, semi-based on Walsh’s own gambling troubles. After that fell through, the script landed on Altman’s lap and he ate it up. Following the lifestyle of two gamblers, Charlie (Elliot Gould) and Bill (George Segal,) California Split is pure Altman; balletic camera and intimate zooms, naturalized acting to help strengthen the supporting performances, and a story that pulls you in by simply stepping into a particular world, in this case, the world of gambling. The hustle and bustle of hustling and busting out has rarely been as immersive, fun, and quietly devastating as it is here, with Gould – working under Altman’s guidance for the third time already – let off his leash to improvise the perfect degenerate role, and Segal turning out to be a great foil as his Bill becomes less passive about “getting in on the action.” For the tech geeks out there, it’s worthy to note that California Split was the first widescreen film to use the eight-track stereo sound system; which helps when you have a director who absolutely loves to drench his images in sound. Be it background noise, dialogue, or music; the sound adds a vital avenue of immersion into Altman’s cinema, and California Split is no exception. This is a must-see for Altman fans. [Nik]

Nashville

Screens August 22

Robert Altman made one of the best American films of all time with Nashville, and one of the most unique. It’s operates in the world of country music, with a kaleidoscope of 24 characters kicking around Nashville in the days leading up to a political rally. The myriad characters’ stories are interwoven, and while the cast is sprawling, the film is a tight, honest encapsulation of Middle America. Nashville is many things: It’s a musical, a satire, a comedy, and a drama all at once, and yet it’s more cohesive than that cocktail of elements sounds. There is no central character, and yet the narrative complexity never gets in the way of our enjoyment.

We see country musicians from the top to the bottom of the country industry, from veteran old-timers to up-and-coming artists, and through them Altman examines American ambition, politics, and big business. He’s a filmmaker of feeling and characters, and I think that’s what makes the film so easy to digest despite the spiderweb of characters he navigates. We’re always living in the moment, observing the fascinating people right in front of us, because he’s in tune with what makes people interesting. A scene in which Lily Tomlin’s character signs with her deaf son about his swimming test is inimitable.

The musical numbers are amazing (I’m a sucker for straight-up, sing-what-you-mean country), with Keith Carradine, Barbara Harris, and the incredible Ronee Blakley singing their hearts out. Critics heralded Nashville as the best film of 1975, and it’s regarded today as one of Altman’s paramount works. The film’s vibrant energy makes its 159-minute running time feel brisk, and Altman’s masterful storytelling has kept the film alive in critics and cinephiles’ hearts for almost four decades. [Bernard]

Popeye

(Note: Popeye isn’t playing in the retrospective, but it’s such an important and infamous film in Altman’s career we decided to include it. Plus it’s kind of an irresistible choice, no?)

Whether you think 1980’s Popeye is a complete disaster or unbridled masterpiece, you have to admit that it is remarkable it was ever made. To pluck a filmmaker with specific sensibilities that don’t necessarily mesh with a standard Hollywood style and then give him free reign on a beloved children’s character? Extraordinary. And then let him make a two hour kids movie that is impossible to follow with a character who mumbles every word? Who thought this would be a good idea? It’s not surprising that Popeye has a less than stellar reputation, but I would suggest it is worth another look. The film’s style is unabashedly Altman’s, perhaps to the film’s detriment, but it brings a one-of-a-kind quality that simply can’t be ignored. Robin Williams, in his first feature film, is magnetic as the title character. Williams hasn’t always shown himself to be the greatest actor, especially when the role lets him be too goofy, but it somehow works here. His physicality, which is an important part of the character, seems to be inspired by the greatest of silent film actors, and is a worthy tribute. Moreover, the performance finds a perfect balance between a real human being and the cartoon character that inspired it. These are undoubtedly caricatures over characters, but every one in the film is given at least one genuine moment that heightens the film — such as Olive’s strangely beautiful “He Needs Me” segment. Popeye is a cinematic curiosity, but it’s also a pretty good film. It is bold, with many genuinely funny moments and very interesting musical numbers. Thinking about the adaptations we often see today, I would argue that we’d be better off if more of them were like Popeye. [Aaron]

Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean

Screens August 23

During the 1980s, Altman turned away from Hollywood and began focusing on the stage instead. He directed Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean on Broadway with Sandy Dennis, Karen Black, Cher and Kathy Bates in the lead roles, and in 1982 he used the same cast in a film adaptation of the play. The four women play former members of a James Dean fan club, reuniting 20 years after the actor’s death in a small Texas town. None of us at Way Too Indie could check out Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean before the retrospective started, simply because it’s not available to watch. The film never received a home video release, but TIFF will be screening it in a restored 35mm print. This might be the only chance to check the film out at all, let alone on the big screen, so be sure not to miss it. [C.J.]

3 Women

Screens August 23

Shelley Duvall as Millie Lammoreaux in 1977’s 3 Women is perhaps Robert Altman’s most unforgettable on-screen creation. Millie is a pretty, put-together girl, but her friends don’t show up to her dinner parties, and they mock her when they do so choose to tolerate her presence. Duvall’s big, deep eyes are cinematic treasures: They can communicate a world of despair, or fear, or desperate rage, as when Millie takes her frustrations out on her stalker-ish, tag-along younger roommate, Pinky, played by a creepy-as-ever Sissy Spacek.

What’s remarkable about 3 Women is its a darkly surreal mood and abstract narrative. The film sometimes seems sweet, though more often it’s eerie and dramatic, verging on a horror tone in its climactic scenes. Duvall, Spacek, and Janice Rule (who plays the third, enigmatic woman named Willie) are riveting in their roles as three women forming a strange, almost supernatural bond. No one’s sure what the film is actually about, but no matter: Altman’s characters and their surprising personality shifts make for great cinema without the need for a clean-cut plot.

Wading through Altman’s twisted dreamworld of chilling sights and sounds is a haunting experience that doesn’t leave you. The actual events that transpire are almost banal in their most literal form, but through Altman’s eye, we see our deepest fears in spilled cocktail sauce and a quiet swimming pool. 3 Women will burrow into the back of your mind like only the best psychological films do, and it’s through works like these that an intimate relationship is forged between audience and filmmaker. [Bernard]

Secret Honor

Screens August 24

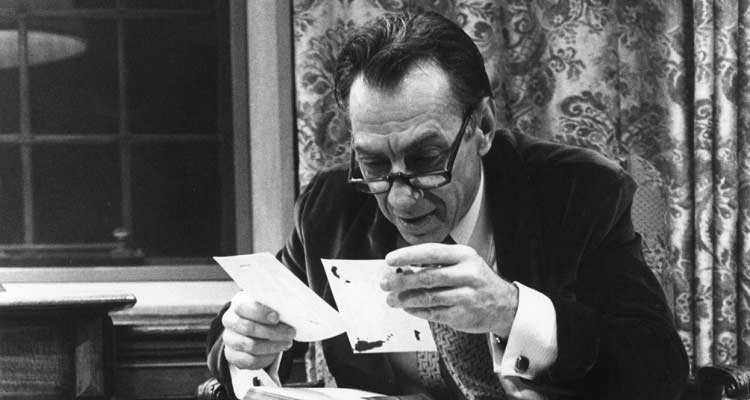

When this retrospective feature was announced, I jumped at the opportunity to watch this odd and atypically introverted Robert Altman flick. If Altman’s filmography ever had a family reunion, Secret Honor would be the distant, outcast cousin talking to himself in the corner. It was born in the 80s, something of a dark decade for Altman; after the turbulence of Popeye set him back, the director found it hard to get any kind of budget, so, during his tenure at the University of Michigan, he adapted this one-man stage play of President Richard Nixon ranting and raving about Watergate, Kissinger, and the American power system into a tape recorder for 90 minutes. It doesn’t have the energy of his busier films and bigger productions, but with Philip Baker Hall’s volcanic performance at the center, you can’t fault it for lacking any energy either. Donald Freed and Arnold M. Stone adapted Secret Honor from their original play into a screenplay that fuels the fire in the picture’s belly, but Altman’s natural cinematic sensibilities still stand out. With his restless camera, dramatic zooms (you almost hear Henry Kissinger’s furious breaths through the paint of his portrait,) and use of score, the mise-en-scène becomes just as crucial to understanding the layers of Nixon’s complex psyche as the monologue. And check this out; Altman had students participate as film crew for course credit, among other more frugal reasons; so not only was he not staying down after taking some blows from the system, he was teaching in the process! It’s a good thing Secret Honor is part of TIFF’s Cinematheque retrospective, because it’ll remind people that Altman wasn’t just great when directing large casts. It’s a fascinating foray into one of America’s most disturbed rulers, that’ll make you laugh during timeouts from marveling at the acting and direction on display. [Nik]

Short Cuts

Screens August 26

It doesn’t get more ambitious than Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, a film boasting a massive cast of 22 characters, all of whom connect to each other in some fashion. Short Cuts broadly connects everyone in the beginning when a fleet of helicopters spray for bugs above the Los Angeles neighborhoods where each set of characters live. As the film progresses, stronger networks form as each storyline begins to intersect with one another. Much of the subject matter involves death and infidelity, but the central theme of the film is accidental luck. For example, a murder is covered up by an earthquake, reinforcing that sometimes life operates in cruel ways. Short Cuts also shows that life always moves on, regardless if luck is good or bad. Altman was known to have large ensembles and Short Cuts is no exception. The film is packed with solid performances from Tim Robbins, Andie MacDowell, Julianne Moore, Robert Downey Jr., Lily Tomlin, Tom Waits, Frances McDormand, Chris Penn, and Jack Lemmon. Here’s hoping The Criterion Collection will finally release a high-def version of this truly wonderful film some day. [Dustin]

Vincent & Theo

Screens August 28

Vincent & Theo was originally a four-hour miniseries for BBC, but Altman cut it down to 2 and a half hours and released it theatrically. If a Film Vs. TV debate was spotlighting this movie, TV would walk away with the win. At 2 ½ hours, it drags without Altman’s usual panache and gets weighed down by Julian Mitchell’s melodramatic screenplay. Tim Roth and Paul Rhys play Vincent and Theo Van Gogh respectively, artist and art dealer siblings in the 19th century, and the two actors do fantastic work with the roles, occasionally breaking into hysterics to liven up the insipid dialogue. Even so, it’s not enough to propel the film anywhere near Altman’s greatest works, even with traces of his natural cinematic sensibilities scattered throughout. The opening sequence sees a raggedy and impoverished Vincent in dire need of immediate dental care while the overlapped dialogue comes from a future auction selling one of his paintings for 40 million pounds. It’s brilliant filmmaking, but much of the remaining film fails to be as cinematically insightful. Perhaps Altman wasn’t as comfortable doing period pieces, but Vincent & Theo didn’t start off his 90s with a bang – a decade which saw Altman re-emerge as one of America’s most important filmmakers with films like Short Cuts and The Player. My sources are a little contradictory on whether the original four-hour BBC cut still exists, but I can see Vincent & Theo working as a broken up slow-burning biographical miniseries way more than it does as a feature film. [Nik]

The Player

Screens August 28

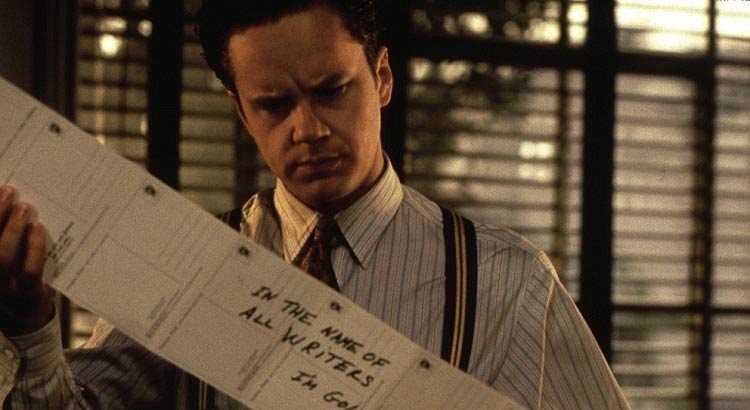

Anyone who has watched The Player would have a hard time coming away thinking of it as anything but incredibly smart and slick. As a murder mystery set in the inner workings of Hollywood, it manages to be uncommonly self-aware without being overbearing. Tim Robbins is utterly convincing as Griffin Mills, a film studio executive whose life begins to unravel when he receives threatening postcards from an unknown writer whose script he rejected. Along with the stress caused by rumours of being replaced at work, the threats gradually drive Griffin into a state of constant anxiety. Yet Griffin is neither the innocent victim nor the sleazy hotshot who deserves a comeuppance – he’s just a real man. As he navigates his career, his new relationship and the increasingly dangerous threats, we’re forced to stop expecting him to be either hero or villain, while Altman subtly mocks the need for either in cinema. Altman’s sly jabs at Hollywood culture are served fast and always on multiple levels, and perhaps most impressive is how well his critiques fit today’s Hollywood as much as they did in the ‘90s. Packed with celebrities playing themselves and contributing to the satirical nature of the film, and a cast of supporting characters with their own complex lives to navigate, The Player refuses to settle into a pattern that we can understand and thereby predict, preferring to constantly subvert expectations – even the expectation of subversion. The pace is admittedly a bit precarious, but in the end, Altman delivers a creation that pushes beyond the bare basics of filmmaking in order to expose its very roots. [Pavi]

Gosford Park

Screens August 30

Probably the second most renowned of Altman’s films next to M*A*S*H, Gosford Park is definitely his second most successful at the box office. And it’s really no wonder. Those same dynamics that keep many of us running back to Downton Abbey each season, are the fuel in Gosford Park’s fire. In fact, Julian Fellowes, creator and writer of Downton Abbey, wrote the screenplay for Gosford Park and then used the film’s basic themes of class distinctions in pre-WWII Britain to create Downton Abbey later. It’s a genius creative pairing. Altman’s talents seem to grow the larger his cast is and Gosford Park has so many roles it veritably demands repeat viewings to keep everyone straight, let alone understand how they all connect. Playing on a familiar theme, as Altman likes to do, the film takes the traditional dinner party-murder mystery and turns it on its head with sheer complicated-ness. Forget the silly British police man (Stephen Fry) solving the mystery, it’s up to a clever maid (Kelly Macdonald) to use her observations of both the upstairs and downstairs societies of Gosford Park to come to a final conclusion. Like some of his other films, Altman gets slightly wrapped up in his characters, not even introducing the main plot point of the film, the murder, until well past the halfway point. But with such polished talent — Maggie Smith, Jeremy Northam, Michael Gambon, Clive Owen, Kristin Scott Thomas — giving such ravishing performances, the film is never tiresome. [Ananda]

The Company

Screens August 31

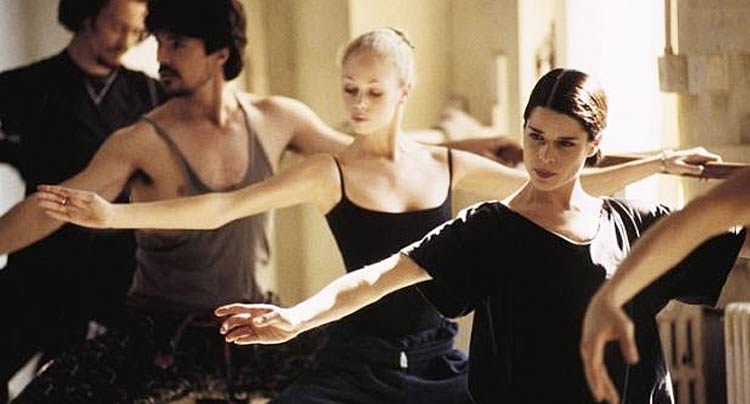

After the success of Gosford Park, Altman surprisingly decided to work on a film he originally didn’t want to do for his next feature. As Roger Ebert notes in his review of The Company, when Altman first read Barbara Turner’s screenplay he said “I don’t know what it is. I’m just the wrong guy for this.” The film was spearheaded by its star Neve Campbell, a former dancer who co-produced and co-authored the film’s story with Turner. In The Company, Altman follows Chicago’s Joffrey Ballet Company for a year, charting the various successes and failures of the company and several of its performers (some of whom are played by real-life dancers in the company). The Company is admirable in the way it forgoes narrative for the most part, with characters like Campbell’s character Ry or Alberto Antonelli (Malcolm McDowell), the company’s artistic director, providing a bare minimum of story. There’s a new, ambitious production being worked on that also provides some sort of narrative, but Altman prefers focusing on the difficult lives the company members lead instead. It’s a scattered, realistic depiction of life in a ballet company, but as a film it can be rather dull. It’s easy to understand Altman’s hesitation towards the material, and for a good amount of the runtime it feels like Altman still didn’t really know what to do with the script. Some of the micro narratives, like a new performer trying to find a place to stay or a dancer snapping their Achilles tendon, succeed in making a compelling portrait of the film’s world. Unfortunately, most of the time The Company plods its way through to the end credits. Altman worked with digital cameras for the first time here, showing how adaptable of a filmmaker he was, even in his later years. [C.J.]

A Prairie Home Companion

Screens August 31

The last film Robert Altman directed is, on the surface, a film about a beloved radio show that exists in real life and is broadcast from the Fitzgerald Theatre in Minnesota. The premise revolves around the theatre being bought by investors looking to tear it down, resulting in the show’s closure. The film is, however, a great deal more than this, with unique and lovable characters that teach us little but enchant us thoroughly, including Garrison Keillor playing a version of himself as show’s host. Altman directed the film knowing he was to shortly die of leukemia, and so this plays a large part in its central themes, especially as it centres around the build up to the show’s last performance. Many aspects of the film are surreal and leave us uncertain of their authenticity, allowing it to transcend the restrictions of belief and truly undertake a more ambitious purpose. The character of the “Axeman” is but one example of this; in literal terms he is simply a man representing the people looking to shut down the show and theatre, but Tommy Lee Jones’ powerful performance makes it impossible to see him as anything but a manifestation of death itself. A Prairie Home Companion is undoubtedly uplifting, and yet it has these touches of darkness that lurk in the corners, meaning every moment of the film comes across as a wonderful attempt to keep beating back those cobwebs and embrace the transience of all things in life – including life itself. [Pavi]