The Poetic Magic of Apichatpong Weerasethakul Ranked

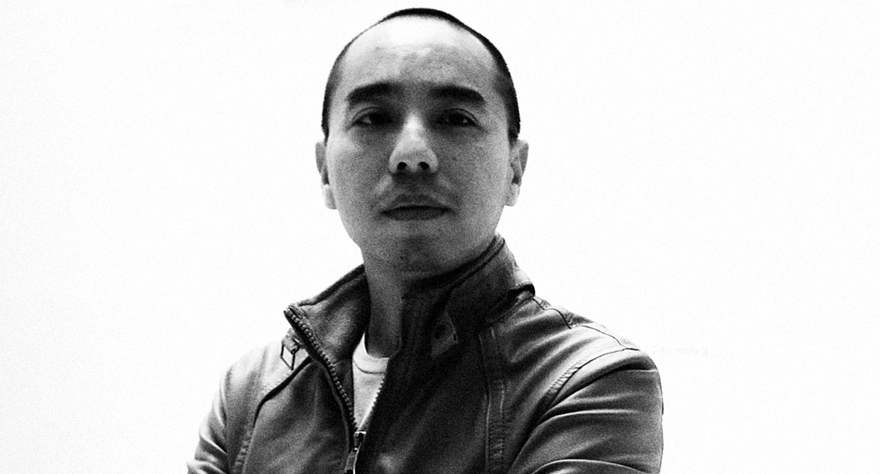

One of the most interesting directors to enter the world of arthouse cinema in the past 15 years is Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Perhaps best known for winning the Palme d’Or in 2010 for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, “Joe” (as he is affectionately referred to by his fans in the West) has a unique type of cinema that is all his own.

Weerasethakul often shoots his films in rural Thailand, his native country, finding powerful and unsettling links between humanity and the world around us through magical realism that is typically shocking in the way it creeps onto the screen seemingly unannounced. By playing with the concepts of narrative and artifice, Weerasethakul is one of the most influential directors working today, and at 45, he seems to have a long career ahead of him.

Weerasethakul’s newest film, Cemetery of Splendour, is about a group of soldiers suffering from a mysterious sleeping sickness in a hospital. It premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival this year, receiving near-universal praise from critics. The film just had its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival (read our review here), and will be making its US premiere at the New York Film Festival. Strand Releasing acquired US distribution rights for Cemetery of Splendour after its Cannes premiere.

Below we rank each of this auteur’s feature-length works, excluding Cemetery of Splendour.

Perhaps Weerasethakul’s only outright “bad” film, this can almost be forgotten, as Joe created it when he was having trouble raising funds for Tropical Malady, and it is the only feature in his filmography for which he is not credited as the sole writer and director. The Adventure of Iron Pussy is a parody of Thai action films, but it is unsuccessful in its satire, as the mere presence of tropes common in Thai action cinema does not make an effective parody. The critical eye toward the conventions of narrative cinema that characterizes much of Weerasethakul’s work seems to be absent, as The Adventure of Iron Pussy revels in the ridiculous elements of its genre rather than commenting on them.

Mekong Hotel is an interesting beast. The oft-cited claim that it is a docu-fiction hybrid is true, but a better description might be that it is a documentary about fiction. The film tells a fictional horror story involving zombies and cannibalism, but while doing so, it documents its own making, capturing the players as both their characters and as themselves, contextualizing the ostensibly non-diegetic score within the same space as the narrative, and showing Weerasethakul himself at times. The idea here is that, by overtly separating fiction from non-fiction, there is some inherent cacophony when attempting to weave the two together, an idea that is touched upon in a more subtle and nuanced manner in most of Weerasethakul’s other work. Mekong Hotel is less complex and developed as his masterpieces, but the concepts explored in this work are certainly interesting.

Weerasethakul’s first feature film was a documentary similar in subject matter to Mekong Hotel, as it explores the nature of storytelling and the concept of narrative. In Mysterious Object at Noon, the supernatural tale of a disabled boy and his tutor is conveyed through the “exquisite corpse” structure, in which a number of narrators each tell a small portion of the story. We experience a cinematic retelling, a staged retelling, and oral retellings by a number of different narrators, each adding their own manner of narration that changes our understanding of the story. Though it is not the most coherent of Weerasethakul’s films (deliberately so), it creates an interesting thought experiment and immediately identified the director as one worth listening to.

Winner of the Un Certain Regard Prize at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival, Blissfully Yours was Weerasethakul’s sophomore feature and the one to establish the ideas and elements that would become common throughout his filmography. It is a slow-moving yet thematically striking film that takes place in rural Thailand, using nature as a lens through which the characters learn about themselves. Nature becomes more than just a place to be in; it becomes a place to be with. The discreteness of the human body is contrasted frequently with the continuous expanse of trees and other foliage characterizing the jungle setting, allowing the film to establish a cosmos of the human body, a method of exploring one’s own sense of being through one’s surroundings. Though difficult to pierce at a first viewing, its mysteries will stick with you long after the credits roll.

Weerasethakul’s first film to play in competition at Cannes won him the Jury Prize, and for good reason: this two-segment anthology film is pure genius. The first part tells a love story between two men, while the second utilizes the same actors to tell a fairy tale of a soldier who gets lost in the forest and meets the mysterious spirit of a tiger. Though initial reviews were mixed, Tropical Malady is now celebrated as a masterpiece, earning the #8 spot on Film Comment’s decade-end critics’ poll. The tangencies and similarities that the film finds between the forbidden love of the first half and the intense mystery and strange confusion of the second are complex and conversation-starting, and while an initial reading might find the film to be rather simple, it is in this narrative simplicity where Weerasethakul’s filmography is able to make the grandest statements about the human experience.

If cinema is about dreaming, then Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives might be the ultimate film, or at least the ultimate statement on cinema, for what is more dreamlike than the remembrance of past lives? There are a number of seemingly unrelated strands in this film, each of which ostensibly represents one of Boonmee’s previous existences. It is difficult to tie these narratives together, even after having seen the film multiple times, but that is absolutely fine, for the purpose of the film is not to provide a cohesive biography of Boonmee but simply to dream, to show us the magic that can exist in the world around us and in the stories that we create. It does not force relationships between the multiple narratives, instead allowing us to formulate the relationships ourselves, engaging the viewer in the storytelling process. Though many were surprised by the film’s winning of the Palme d’Or over competition that included Another Year and Of Gods and Men, the decision has certainly gone down as one of the Cannes jury’s best in recent memory.

Weerasethakul’s best film is the only one out of his past five (including Cemetery of Splendour) to not play at Cannes, instead finding a spot in competition at the Venice Film Festival. To say too much about Syndromes and a Century would be to spoil one of the most befuddling, frustrating, maddening, and ultimately rewarding cinematic experiences of all-time. There is an unsettling feeling throughout the film not only that everything that happens has happened before and will happen again, but also that the characters are aware of this fact. The line between fiction and reality is crossed multiple times, often unnoticeably. Calling it self-aware would be a reductive and patronizing oversimplification, and calling it a fever dream ignores its calculated insanity. With Syndromes and a Century, Weerasethakul made his grandest and most complex statement on the nature of narrative while keeping it his subtlest. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives and Tropical Malady might be the most entertaining, but Syndromes and a Century is the most mysterious and powerful of his works. Weerasethakul’s filmography seeks to unlock the full potential of cinema, and in Syndromes and a Century, he succeeds majestically.