Inside Indie Filmmaking: Development and Pre-Production

Development and pre-production. I know for many of my peers this is the most dreaded and dreadful phase of the process: having to sit, plan, and assess all the variables before the “fun” can begin. I’ve actually grown to love these parts of the process. Making films is chaotic and messy; and for me, pre-production is the only time I have complete control over everything—including the pace. Sure, momentum is key, but learn to love this phase of production, because it is the last chance you’ll have to catch your breath before the next several months line up to take turns beating you to a pulp. The quality of work you do now will dictate just how well you can take the impending beatings.

I’ll try and keep this as focused as possible. Like all of the topics I’ve discussed up to this point, I could talk about pre-production endlessly–but don’t worry, I won’t do that to you.

Legal and Contracts

You should have your legal support in place at this point—since you needed them to help in the fundraising process. While there are contract templates all over the web (and most of them should work just fine for your production with regards to location releases and background talent) if your end goal is sales and distribution, be sure you have your ass covered.

Most importantly—and I cannot stress this enough—do not begin any official work with any crew without a contract signed and in place. It’s to protect you as well as the person you are dealing with. If they are working for you and working on production, a gentleman’s agreement will not be enough. Make it official.

I fired a number of people on my show. I wasn’t popular for it, but it was necessary for the overall integrity of the project, and to protect what my investors had put their money towards. One individual was a producer I brought on very early in the process—before I was even set up to have a contract prepared. After four weeks, I decided it wasn’t working out and removed them. Though we never had a signed contract, we had discussed terms and made a verbal agreement. After I fired them, I offered to pay out the amount discussed up to that point, acting as though a contract had been in place.

The individual decided that wasn’t good enough, and demanded $15,000 in compensation for their time. I refused, and was eventually taken to small claims court over what was initially a much smaller amount, and ended up paying more than what was originally agreed on. It got pretty ridiculous—I even received several offers to appear on a number of court TV shows, including the honorable Judge Judy—but we eventually settled the matter in our county court 6 months later.

If you don’t have the official contract papers, at least put everything in writing. Protect yourself, and keep things transparent.

Here are a few elements I did not have in place in my original cast and crew contracts that I will make sure I have in all future contracts:

- A termination clause.

- A ‘no-compete’ clause for larger talent (within a reasonable span of time).

- Appearance and promotion agreements.

- Obligatory task stipulations and terms for above-the-line crew through the entire duration of production.

Wisdom I am happy to pass on. Don’t be unreasonable, that’s why unions exist, but protect yourself and your crew.

Crewing up

This may be geographically dependent, but only in regards to experience and abundance. In Boise, Idaho, my options were obviously going to be a lot different than in LA, Seattle, or Austin. Regardless of where you are, do not hire someone just because of their work or reputation—get to know them on a personal level. This is a relationship you will need to maintain for several months and in varying degrees of stress and turmoil. The number one thing to consider: Is this someone you COMMUNICATE well with? I said it before—filmmaking is nothing more than a giant exercise in communication. It doesn’t matter how much money you have, how great of a script you wrote, or how many times you have seen The Godfather. If communication fails among your crew, everything will go to hell. Fast.

For me, the four most crucial roles in terms of set operation and overall execution are the director, assistant director, production designer, and cinematographer. If all four of these department heads are grooving and in good synchronization, you are going to have one hell of a shoot. Every time I had an issue with a scene or set-up, or needed to decide about blocking and execution, there was never a decision made without all four of us working it out together—even if it meant sending the rest of the crew to break or an early lunch. (Avoid wasting other people’s time or cluttering your decision-making process by trying to work things out in front of the crowd.)

Allow each department head to manage their own department and you will have nothing to worry about. Approach your crew-hiring process with the focus of these department heads functioning as a solid unit—not as individual elements. Make sure you all COMMUNICATE well as a team.

Oh, and spend the money for a good script supervisor. I love you, Lisa!

Locations

I learned a lot about cinematography and scene structure through location scouting with my DP. A location may look really great through your eyes, or have the ‘character’ you pictured, but that does not mean it will photograph well or be a good place to assemble a G&E crew. Once you have your DP onboard, include them in all your decision-making processes about locations from the start. Again, also include your production designer and AD. If a set is un-dressable, un-lightable, or un-accessible, you aren’t going to achieve the cinematic depth needed to have it look, you know, cinematic.

Here is where negotiating will save you big. (Take this approach to all elements of your pre-pro). Never approach a location or deal asking for a favor. Take the stance that you are doing them the favor by being there. As with investors, be respectful, and when the deal goes through, be eternally grateful. In the approach, let them know the film is being made regardless, but you would love to have them be a part of it all. If it isn’t meant to be, it isn’t meant to be; there are other options for you. (If you have a name talent attached, now is the time to start dropping that bomb. Again, people like having something to be excited about.) The only locations we had to pay for were city owned properties.

Script Breakdown

Not that you’ll have a locked script at this point—or possibly ever—but it will be close enough that you’ll be able to get the basic elements squared away. You should go through this three times: once with your art director, once with your AD, and once by yourself to know where you all stand.

Do an art direction breakdown. This goes beyond the typical necessities of wardrobe pieces, props and basic set-dress elements. Identify the sub-elements, and the moments in the script where character arch begins to impact the visual aesthetic of the film. Of course, for that to happen you need to identify the initial aesthetics: color palette, subtle wardrobe cues, and other telling visual details.

In the beginning of my film, Almosting It, the protagonist and his friend live in a world of red and brown. His place of work, a retirement home, is filled with yellow and green. Quinn, the love interest, dominates her realm with blues. As Ralph, the protagonist, begins to fall for the girl, his palette shifts from red to blue. (This moment is literally depicted with a scene of red balloons being released into the blue sky). At the climax of the film, when big decisions are made and conflict resolved, Ralph’s wardrobe is white and grey.

Identify not only what is needed with the art direction, but where in the story these elements need to subtly shift.

Breakdown with the AD. This is the more technical breakdown. Scheduling: What/who needs to be where/when. A well seasoned AD will have this covered, and you are mostly present to answer practical questions, not creative.

Your own break down: It’s just good practice so you can confidently answer any question.

Shot-lists and Storyboards

I’ll be honest, I’m probably not the person to take advice from on this one. This is another area where it works for me, but likely no one else. I’m sure in another year or so—after I’ve done a few more films on a larger level—I’ll travel back in time to this moment and tell myself to “shut the hell up,” but for now this is how I feel.

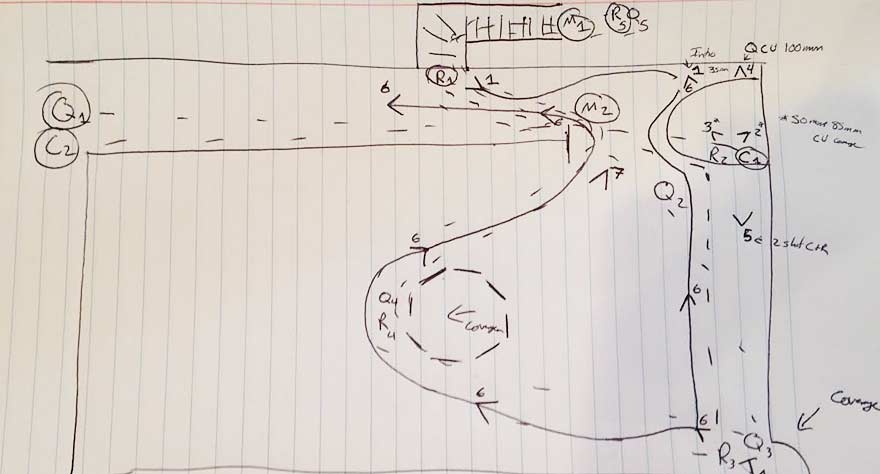

I don’t really believe in shot lists or storyboards. I do them to force myself to think about each scene ahead of time, and to keep my AD happy, but I eventually go into every setup knowing all the boards and lists will get thrown out the window. It’s inevitable, and has always proven to be the case. You show up, get set, then immediately realize what you planned for isn’t right or isn’t going to work. Accept it. Be ready to think on your feet. Be sure you get coverage, but the shot list you had in mind is now worthless.

This turned out to be the case on the biggest scene of the film. I wrote a typically outlandish Will von Tagen-scene. The kind my DP makes me swear I will never write again, but always do. It was the climax. It involved boats, multiple cameras, difficult re-sets, tracking gimbal shots, stunts, a duck—it was as if I watched The Making of Jaws and thought, “Oh hey! That looks like a good idea!”

We meticulously planned it out. Blocked it. Prepared for every thing. When we showed up to shoot, the second boat we planned to use for half of our shots was inoperable. We only had enough wardrobe for two re-sets. The second camera wasn’t calibrated. The location wasn’t aware of the stunt work we had planned. Other than our on-land camera positions and basic action, all our prep was next to worthless. We no longer had a shot list for the day.

Your Cinematographer/Director Relationship

What’s more important than shot lists and storyboards is establishing a shooting style with your cinematographer. Established aesthetics are what will carry you through in the end. I knew I wanted long-take scenes that could potentially play out in just the master take. I wanted interesting and interactive blocking. I knew I wanted as much natural light usage as possible. We had limited means to move the camera, so we had to come up with ways to engage the actors. If both the actors and camera weren’t movable, we move the environment instead (hence shooting on boats). These are the conversations we had ahead of time as opposed to planning a shot list for each scene.

We both knew the look we wanted, what we had to work with, and how our locations would help or hinder this aesthetic. When a planned shot didn’t work, we had enough awareness of our assets that we were able to figure things out on the spot, and still stay consistent with the ‘look’ we planned out.

Discuss your lens option. We only used three different lens sizes on this shoot, and almost lived exclusively on one.

The 35mm was our number-one go-to. All our master-takes and establishing scenes were done on this lens. Even a good deal of coverage. It just worked.

We used our 50mm sparingly for basic, typical coverage.

The 85mm was brought out only when we really wanted to make a moment stick.

That was it. We realized early the 35mm was our guy, and we ran with it. Supplemental light was used to build depth in a scene where it was needed, or add contrast to evoke emotional response—largely subliminally and without drawing attention to itself because that’s what good lighting is supposed to accomplish.

Again, I feel I would be doing a disservice to recommend this style, and maybe one day I will feel opposed to what I have just said. This is how I work for the moment, and it works well for me. I think endlessly on blocking and how I want my shots to feel, but I know that on the day, I need to know I can work with whatever limitations or spur-of-the-moment ideas present themselves on set.

Post Pre-Production

There are infinite areas I could continue to discuss, but a process spread out over months is difficult to break down. The most useful thing you can do is learn to negotiate and think on your feet. Learn to protect and cover both your ass and assets. Know your script, even if it will likely change another 20 times before you are done. Have an idea of what is required to visually show your character arcs and transitions, and be aware of any set or resource limitations.

Most importantly, build a good team of people you trust. In the end, they will make sure you all come out with something to be proud of. Finally, learn to love the process. As much as things will change between now and final cut, this is where the seeds are planted—and without a sturdy foundation, even the most gorgeous house will collapse in the fury of the storm. (Or when communication fails. Did I mention communication is important?) Have fun and take a deep breath—it’s the last one you’ll get for several months.