An ambitious documentary that tries its best to squeeze two hours of material into 94-minutes.

An ambitious documentary that tries its best to squeeze two hours of material into 94-minutes.

It’s hard “shocked” when information about a celebrity’s past is revealed. Nowadays information about someone gets dredged up by the TMZs of the world and distributed ad nauseam across social media. Plus, there is very little a celebrity could have done in his/her past that an older celebrity hadn’t already done, so when we hear of something that is supposed to be surprising, we yawn because we’ve been there, done that, and seen the retweet. But there’s always an exception to prove the rule.

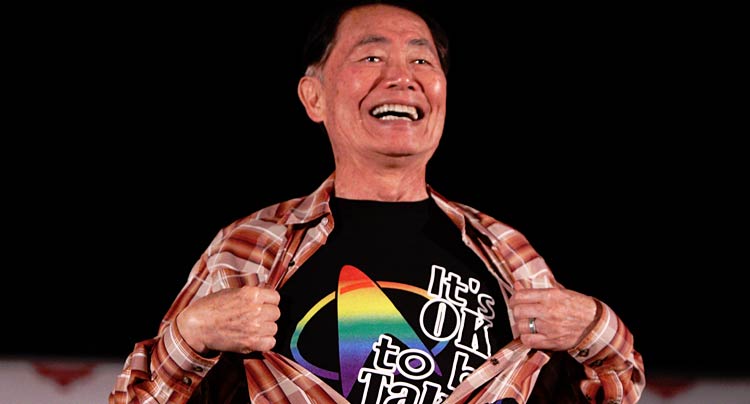

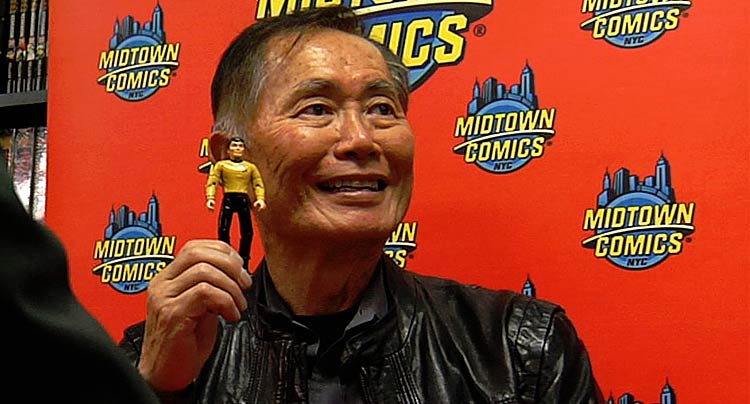

Such is the case with To Be Takei. The non-linear documentary presents the life story of George Takei, who is best known for his role as Lieutenant Sulu on TV’s Star Trek (and in the later Star Trek film series that spun off the original TV series). More recently, the gay actor has become known for his efforts in promoting Marriage Equality, and he has become quite popular on Facebook, boasting almost 7.5MM Likes (as of this writing). But what is surprising – and about as non-scandalous as a celebrity backstory can get – is the tale of Takei’s childhood and his time spent with his family living in a Japanese internment camp during World War II.

Because the star’s life has been so diverse, director Jennifer M. Kroot (It Came from Kuchar) roots the story in Takei’s relationship with Brad Altman – his husband and personal manager. She uses the daily life of modern-day Takei/Altman as the film’s hub, and then visits (and revisits) various story “spokes,” yet always returning to the hub. Those spokes include the couple’s younger days (including their meet-cute); Takei and Altman’s relationships with their mothers; the actor’s run on Star Trek (complete with new interviews with original cast members Leonard Nimoy, William Shatner, Nichelle Nichols, and Walter Koenig); his non-Star Trek acting career (including career regrets); the modern-day phenomenon in that is George Takei (appearances on Howard Stern, his Facebook page, his lucrative convention appearances, his recent television cameo work, and so on); and his work as a champion for Marriage Equality. There’s even a spoke about Takei’s foray into Los Angeles politics in the 1970s, where he worked to help Tom Bradley become Mayor, and where he was an integral part of LA’s public transit system.

His is a life that has been well-lived, and all of it is entertaining and educational. But it’s also the stuff you get free, because what you pay for are Takei’s stories about being interred (as a child) with his family by the United States. In the wake of the bombing of Pear Harbor, the United States government – in one of its darkest hours – rounded up Asians and, for all intents and purposes, imprisoned them for fear they were Japanese sympathizers. Takei talks about this specifically for the doc as well as in as a public speaker (used in the doc). His anecdotes are mesmerizing, and the creative outlet he has explored to share his story beyond this film (I won’t spoil that here) is amazing.

If only there were more of that and less of the other stuff. Just as we are jaded when it comes to big reveals about celebrities’ pasts, so too are we jaded by much of the “growing up” moments of celebrities’ lives, entertaining or not. Takei’s Star Trek years put him on the map, yes, but everyone knows this. The parts about his being closeted during that era (and beyond) are noteworthy, but the periphery is old. And the (semi-real?) cat-fight that’s played up in the doc between Takei and Shatner is terribly out-of-place and a waste of precious film. This is a chance to hear significant (read: outside of Hollywood and with real stakes) history from someone famous. The coverage here is fine, but more of this alone could have filled an entire film.

The hub is odd, too, from this perspective: Takei, when on camera in the present day, tries too hard to be the “Takei Character.” His rich baritone is a little more smooth, his speech cadence is a little more intentional, and he laughs at the end of almost every sentence. It’s as if he knows he’s on, and it’s only made clear after the footage of him doing public speaking gigs is introduced, where he is much less “on” and much more genuine. There’s also a glaring dearth of paternal references. Outside of the internment tales, Takei’s father is hardly mentioned, and the same applies to Altman’s father; both mothers get plenty of spotlight, though. It makes you wonder how the fathers of a past generation viewed their gay sons, which makes you wonder why something so personal would be left out of such a personal film.

To Be Takei is an ambitious documentary that tries its best to squeeze two hours of material into a 94-minute film. It doesn’t always work, but when it does, it’s something special.