Performances are the main selling point as the content is dull and insubstantial.

Performances are the main selling point as the content is dull and insubstantial.

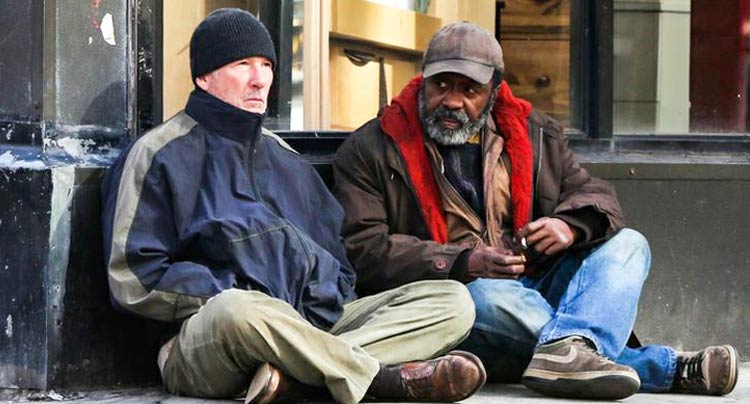

Sleeping on park benches, in emergency room waiting areas, or the bathtubs of recently evicted apartments, Richard Gere is far from the suave, charming persona he normally assumes in his roles. Directed by The Messenger and Rampart filmmaker Oren Moverman, Time Out of Mind casts Gere in the role of the homeless, alcoholic protagonist shuffling down the busy urban New York City landscapes. As George Hammond (Gere) moves throughout the city he’s treated with varying levels of compassion, both from people he knows and complete strangers.

It’s not until nearly halfway through the movie that George enters a homeless shelter and begins to accept his situation as well as the realities of how much he can expected from those around him, including his estranged daughter (Jena Malone). In the time before then, Time Out of Mind uses an excessive amount short scenes that illustrate daily life on the streets to highlight societal indifference towards the homeless. These scenes intentionally obscure the focus by shooting through windows, the glass panes of doors, and off of rooftops. Likewise, Time Out of Mind layers in the incessant sounds of overheard cell phone conversation and distant police sirens that cannot be avoided in New York City. The effect allows the film to be one of the strongest auditory representations of how the city sounds, but it’s ultimately to the detriment of Oren Moverman’s movie. The techniques are jarring and become frustrating as they feature for a large part of the beginning in place of actual plot.

In his first two films (The Messenger, Rampart), Oren Moverman’s ability to draw nuanced performances from his actors (notably Ben Foster and Woody Harrelson, twice) is rooted in the movies’ thoughtful approach to character study. Time Out of Mind demonstrates a similar patience but fails to deliver as much depth. Gere delivers a quiet performance as George that is among the best roles in his career considering his limited range. Subjected to being outside the frame and in the background of many scenes, his limited opportunities to offer texture to the character are only a touch away from caricature. A greater actor might have been able to do more with the part, but it’s a decent turn from Gere.

The energy of the film changes considerably with the arrival of Ben Vereen’s Dixon, a homeless man of questionable mental health who talks nonstop but is one of the first people in the story to show any kindness towards George. Dixon aids George as he accepts his status and begins to work on improving his life in some of the few scenes that provide forward momentum to the movie. Like most of the elements in Time Out of Mind, the repetition in this section becomes wearing and the film does little to shed new light on the plight of the homeless.

The sentimentality in the second half of the film gives Time Out of Mind some redeeming empathetic scenes but is entirely expected, and indistinctive. By that point, the methods implemented by Moverman to show George’s invisibility to the outside world only serve to distract from the rest of the film. While many of the performances are solid, the content in Time Out of Mind is dull and insubstantial.