Unexpectedly revealing biopic of a genius of his craft.

Unexpectedly revealing biopic of a genius of his craft.

Following his recent announcement of a retirement from directing, it’s difficult to ascribe any thoughts to Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises without also finding the analogue between himself and his subject. Both are concerned with the aspirations of a life’s work and the implausibility of trying to assess this work in hindsight. Rather than trying for the ambitious, all-encompassing masterpiece to the kind of surreal, fantastical worlds that saw his imaginative vision the most revered in animation from any nation, The Wind Rises dials it down, bringing it all back home to Earth. With this straightforward biopic of aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi, Miyazaki offers viewers his most subtly restrained and arguably “grown-up” work in years.

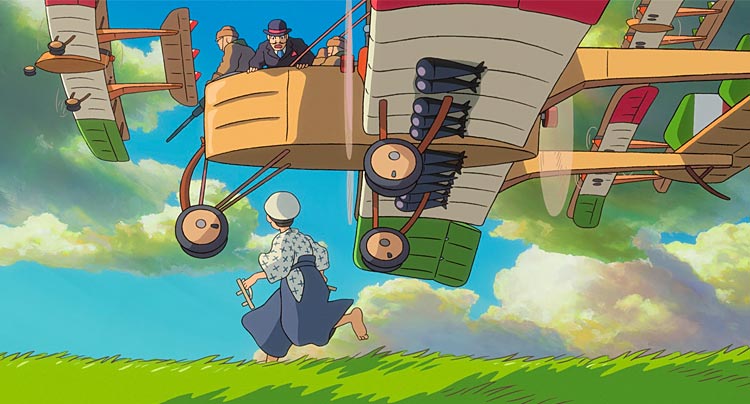

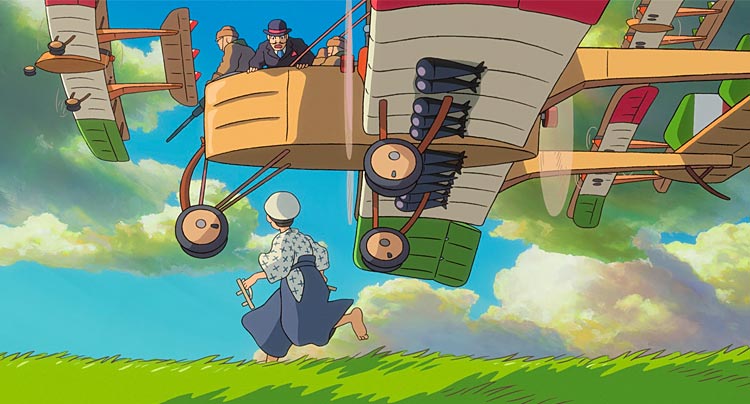

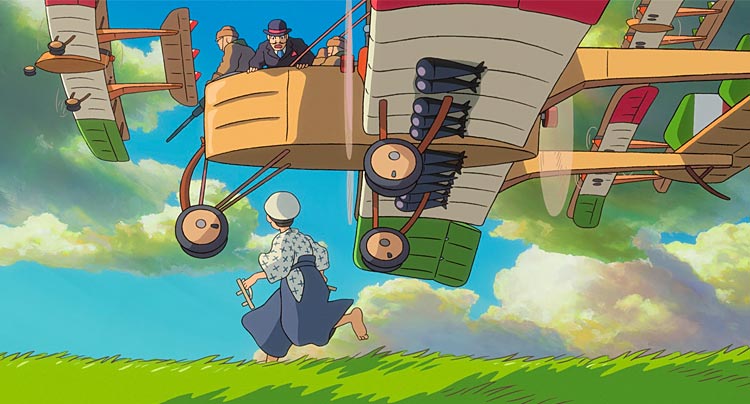

That Miyazaki adopts a traditional three-act structure following Jiro through childhood, adolescence and adulthood does little to suppress the profound power of his wonder-filled imagery. Instead, the long passages depicting the gritty, harsh realities of early thirties Japan serve to underscore the otherworldliness of his dream sequences, in a manner most similarly achieved by Guillermo del Toro in 2006’s Pan’s Labyrinth. The many foreboding, and frankly apocalyptic, visions of Jiro’s creations causing destruction suggest the deeply humanist or environmentalist thread that runs through Miyazaki’s oeuvre and, simultaneously, the subconscious reservations Jiro holds for the capacity of his designs to cause harm.

The film has an encouraging complexity that results in occupying this troubling space, with the idea that art has an inherent potency and power that, like anything that contains embedded energy, can be manipulated or misused by the hands of its beholder. Miyazaki’s thesis is that such matters are beyond the realm of the artist, whose responsibility to the world is merely to enrich it with their innovation. So much attention has been drawn to the political and moral dimension of Miyazaki’s taking this stance; his perceived indifference some attribute to an awestruck representation of Jiro’s designs, which were used prominently in Japan’s World War II efforts. I applaud the boldness of a director interested in seeking something truer and more universal within his work: if that truth is more difficult to palate, less distinctly leftly or rightly leaning, then so be it. Who would live in a world without Pyramids?

The Wind Rises is unlike Spirited Away or Princess Mononoke, which in the final analysis might vie for chief position amongst Miyazaki’s finest works. Its appeals are less immediately present, like a record that needs several spins before it grows on you and begins to saturate your thinking. Slower and more deliberate, the film is nonetheless loaded with exquisite matte backdrops packing the kind of selective detail that remind us of the complete command over every minute element of visual storytelling Miyazaki had learned over the better part of 75 years drawing, rendering and animating. When the backdrops themselves move, like in an earthquake sequence that is the picture’s early action centrepiece, it’s a shockingly cathartic experience that speaks to an overarching theme of giving oneself over to the laws of nature. Its forces — earth, rain, fire and the titular wind — continually propel Miyazaki’s characters into situations where they come to understand aspects of themselves and one another.

It’s less hokey than I make it sound, even when we consider a central love story (with saintly, chance childhood acquaintance Nahoko) rounding out the life of a man who was guilty of an almost defeatist commitment to perfecting his work. Defying the sentimentalist traps of its controversial, artistically-licensed inclusion into Jiro’s real story, its earnest and humbly sincere presentation refuses to be trivialised or marginalised as unnecessary fluff: it’s moving, goddamnit, when anyone tells anyone they would wait one hundred years to be together, because a hundred years is such a long time.

If this is to be it, then Hayao Miyazaki has gifted us with one last work of understated mastery. The Wind Rises represents no showboating, no easily digestible adventure. It’s a hard, devastating and uncompromising work of art that holds deep-seated insights into the difficult nature of having art as one’s calling. As a closer to a storied and rich career, we can ask of nothing more from the man than that.