The documentary makes sure to keep its subjects at an arm’s length so they don’t earn any pity.

The documentary makes sure to keep its subjects at an arm’s length so they don’t earn any pity.

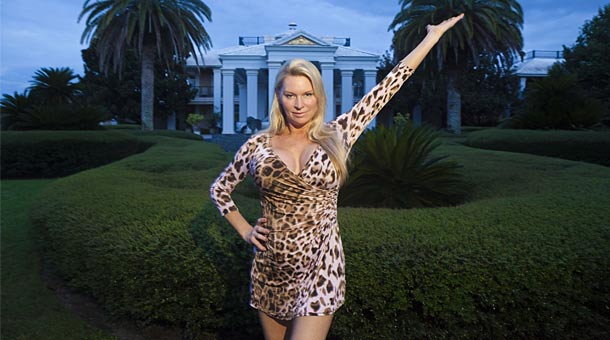

When Lauren Greenfield set out to film the Siegel family for The Queen of Versailles, she probably had a different film in mind. Jackie Siegel is the 43 year old mother of 7 (with one “inherited” as she puts it) whose husband, David Siegel, owns the biggest timeshare company in the world. The documentary’s title comes from the name of the house David and Jackie are building. Inspired by Louis XIV’s palace in France, the 90 thousand square foot home would be the largest house in America. Jackie gleefully rattles off facts about Versailles: 30 bathrooms, 10 kitchens, a ballroom, a baseball field and an ice rink to name a few. Their current home, a mansion with garish paintings of the family among other absurd extravagances (one of Jackie’s old dogs is stuffed and placed in a glass case), already feels cramped for everyone at only 28 thousand square feet.

The documentary, which started filming in 2007, shows the Siegels when they appear to be on top. Westgate, the timeshare company David runs, is celebrating the opening of their newest building in Las Vegas and on its way to earning over a billion dollars for the year. Once the market crisis of 2008 hits things change dramatically. Westgate made most of its money by aggressively selling their timeshares to middle class customers who couldn’t afford what they were buying, and soon enough the company is crippled under a massive amount of debts. Versailles is put on the market despite construction being halfway done and the Siegels suddenly find themselves with financial limits.

It’s this turn of events that transforms The Queen of Versailles into a surprisingly empathetic look at Jackie Siegel as everything around her begins to crumble. Greenfield’s point throughout Versailles is to show how the 2008 crisis impacted everyone similarly, even if the scale of the Siegels troubles is dramatically different from the middle class Americans who suffered most of the damage. The Siegels, like many Americans, thought they had more money to spend when they were actually worth far less. Early on David explains that people will take out mortgages on his timeshares because they love to feel rich even if they aren’t. Of course he didn’t know that he was falling for the same pitch he was selling by feeling richer even if he was merely a millionaire instead of a billionaire.

Greenfield could have easily kept the mocking tone of the film’s extravagant first half when the Siegels began to suffer, but she decides to focus in on how the financial strain begins to affect the family. Jackie, still maintaining her optimism, tries to deal with her home turning into a mess (the housekeeping staff is reduced from almost 20 people to 4 nannies). David becomes more deplorable as he hides away in his cramped home office and lashes out at his family repeatedly. The documentary makes sure to keep its subjects at an arm’s length so they don’t earn any pity. Scenes like Jackie’s failed attempt to have a birthday dinner for her husband are hard to watch, but when Jackie admits that she only kept having children because maids could take care of them for her it serves as a reminder of how her family doesn’t deserve any sympathy.

The Queen of Versailles ends when the Siegels appear to be at their lowest point. David, sitting down for an interview, mostly begs the crew to wrap things up so he can get back to saving his company. In the film’s final scene, catching one of the family’s more candid moments, David fights with his family over all the lights being left on in the house. Jackie tries to talk with him, but he brushes her off while complaining about the electricity bill. While it may be a sign of how far the family’s status has fallen since the start of the film, it’s also the only moment that could be described as relatable.