Deliberately slow-going, and even though the film is visually arresting, its grip on my attention loosened at times.

Deliberately slow-going, and even though the film is visually arresting, its grip on my attention loosened at times.

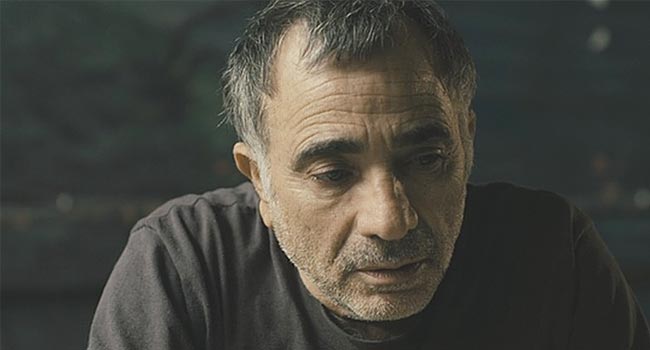

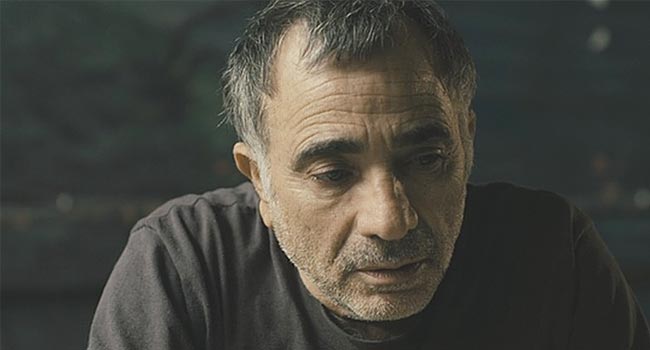

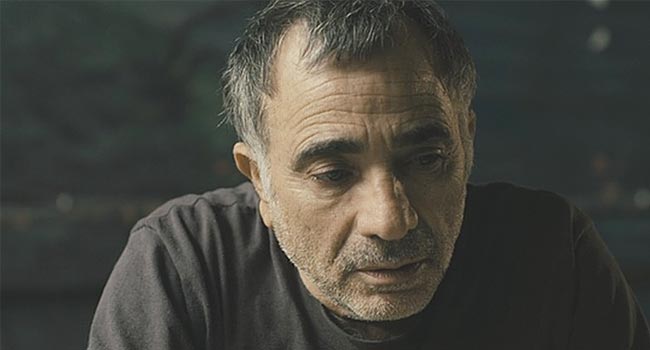

Set in a sun-toasted Israel, first-timer Idan Hubel’s The Cutoff Man is a patiently reflective tale of an old man named Gabi (veteran Israeli actor Moshe Ivgy) whose dignity is slowly stripped away by a thankless (putting it mildly) job as a “cutoff man”, disabling people’s water supply when they don’t pay their bills. Hubel explores how a broken economy can drain the humanity and empathy out of a community.

The The Cutoff Man begins with an unemployed Gabi being offered a job as a “cutoff man” at the employment office. He accepts without hesitation, as he’s barely scraping by. We watch as he starts bouncing around town, hunching over in front of pipes and cutting off his fellow townsfolk’s precious water supplies. Hubel’s camera is patient and still, highlighting the elbow grease it takes for Gabi to twist and turn the pipes with his tools. The meditative pace and aura of the film recalls Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry.

Gabi’s first “victim”, an elderly woman, hobbles after him when she discovers he’s just cut off her water. She pleads with him to stop, but he just keeps walking, too guilt-ridden to look her in the eye. His subsequent “visits” don’t get any easier. He gets yelled at, called names, physically threatened, and morally battered. People look at him with utter disdain, like he’s death himself, rendering Gabi’s pride demolished. Still, Gabi trudges on, as not providing for his family isn’t an option. Still, he’s only scraping by, barely able to pay for his son’s goalie gloves. Hubel and co-writer Nimrod Eldar aren’t quite as cruel to their protagonist as, say, the Coen Brothers, but he’s certainly got enough sad-sack in him to fit right in with Jerry Lundegaard and Larry Gopnik.

As Gabi’s list of angry “victims” grows, his reputation as the feared “cutoff man” begins to sabotage his home life. He’s forced to cut off the water of his son’s soccer coach, resulting in the vengeful coach benching Gabi’s son during a game where scouts are in attendance. In a quietly brutal scene, Gabi sinks several hard-earned shekels into a vending machine while he weeps out of desperation and anguish. Ivgy doesn’t have many lines, but he doesn’t need them—you can feel his spirit deflating ever so slowly as his face droops and his tired feet shuffle. By the end of the film, he’s a shell of a man, though his commitment to his family admirably remains intact.

Hubel’s storytelling is deliberately slow-going, and even though the film is visually arresting (his compositions are great), its grip on my attention loosened at times, though it never completely lost me. Ivgy’s slow, gloomy descent into agony and desperation is akin to Antonio Ricci’s downward spiral in Vittorio de Sica’s terrific Bicycle Thieves. While Gabi’s story easily could have been told as a short film, the added length helps the emotional heft of his plight sink in deep.