The latest reflection on Steve Jobs' life seems overly eager to compensate for all the hero worship of past films on its subject.

The latest reflection on Steve Jobs' life seems overly eager to compensate for all the hero worship of past films on its subject.

The official Apple website posted a black-and-white photo of former CEO Steve Jobs with the text “1955-2011” on the night of Oct. 5, 2011, and within minutes the Internet was ablaze with reflections on Job’s untimely death to pancreatic cancer. Wired quickly followed, with a memorial splash page, a completely black background accompanied by quotes from influential public figures. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg thanked Jobs for “showing that what you build can change the world.” Just when it seemed like the entire Internet might have collectively gone somber, the satirical newspaper The Onion spoke up with the headline, “Last American Who Knew What The F*** He Was Doing Dies.”

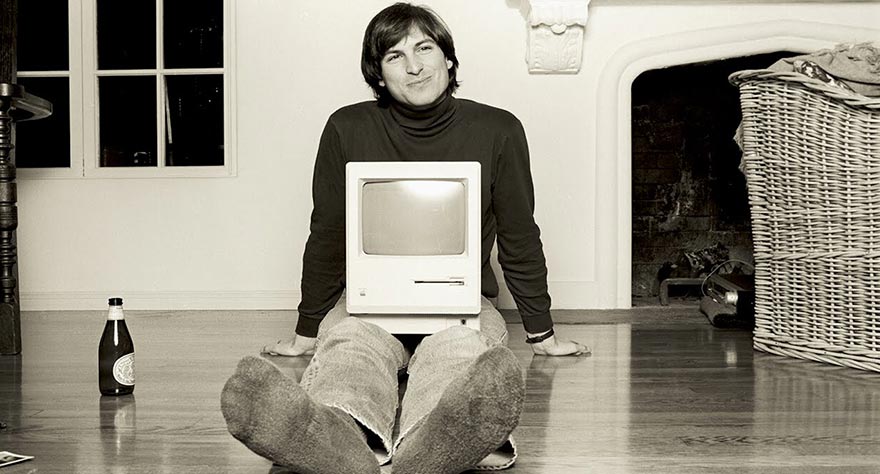

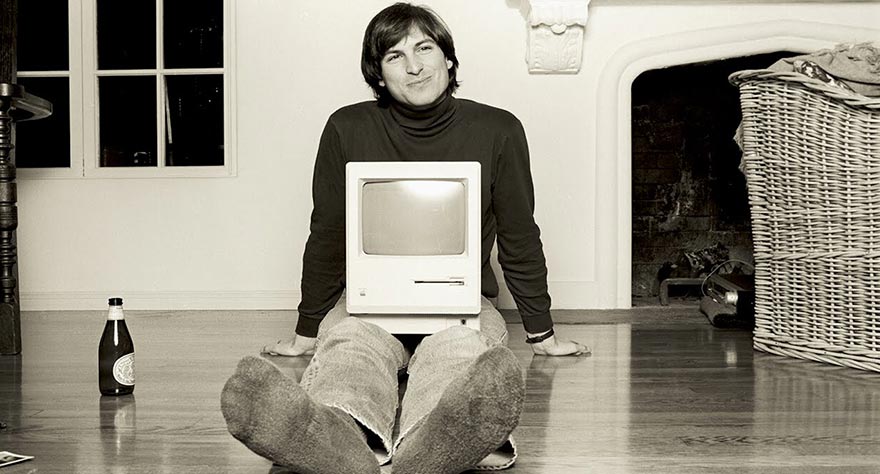

It was a death that seemed to cut people deep, and director Alex Gibney, inspired by the world’s response to man who didn’t save lives but made things, sought out to understand just how that response came to be. What he learned turned into Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine, a documentary that takes an unflinching look, maybe for the first time, at the man behind our most beloved devices.

Time can certainly bring perspective, and what makes The Man in the Machine different from earlier made-for-TV documentaries, and certainly different from the 2013 feature-length film Jobs starring Ashton Kutcher, is Gibney is not too shy to derail some of the legend. Jobs is a figure people like to romanticize, a pioneer who dropped out of school to pursue creative passions instead. A man who stood up to the 1980 version of Goliath (IBM), and dared to make something based on values like quality and aesthetic purity. But Gibney, known for pulling the curtain on some big-league scams with his documentaries Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks, isn’t so interested in expanding upon the Jobsonian myth. The overall tone feels a bit critical, even to the point of editorializing at times.

This works to mixed results. The Man in the Machine is the first time that Jobs’ former girlfriend (and mother of his child), Chrisann Brennan, is featured in a substantial and honest way. Through an endearing interview where Brennan at once seems to fall in love with Jobs again and re-experience the rejection, the filmmakers pan down on a legal document showing Jobs trying to frame his ex-girlfriend as a woman with multiple partners, so he can shirk parenthood and continue playing with circuit boards in his garage. That’s the interview a definitive documentary on Jobs needed to get. Also nice is a thread that continues throughout on Jobs’ attraction to Buddhism and enlightenment. Filmmakers even manage to track down a monk he interacted with on the week of the Apple I’s creation. Considering Jobs eventually would die after trying nine months of alternative medicine, it’s nice to see how Eastern traditions were such a large part of his life and who he aspired to be. But even these parts poke some fun—the monk jokes that he’s still not sure if that first logicboard qualifies as enlightenment.

It’s worth interrupting here to note that an interview with Joe Nocera, a Time magazine technology reporter, shows some of the problems with being critical of Jobs. Brand loyalists love Apple, perhaps to irrational levels. Nocera recalls writing stories on questionable Apple practices—backdating stock options, shifting profits offshore, bad working conditions in their Chinese factories—and getting nothing but hate in the comments. People love Apple. They don’t want to hear it. So while I think this section of the movie drags the most (at one point during the Foxconn section, Jobs largely disappears), perhaps some of my reluctance in viewing can be rooted back to the movie’s greatest obstacle: Jobs has a lot of fans. However, I think this part of the movie that shifts from firsthand interviews to news segments about Apple’s misdeeds (with occasional quips from Jobs from old interviews) just feels too much like editorializing. It feels like the film is trying too hard to be contrarian to what’s already been done on the man. The movie becomes more about Apple than about Jobs, and no matter how much we can speculate that he had to have known, he simply is not the company. Without directly tying him to the events in China, it feels like a stretch. As though the movie’s main theme is “How Apple is not as good as you think,” and not about the man himself.

But for those who have kept up-to-date on past Jobs-based films, the attempt to be different does often still pay off. It’s nice to focus on 1998 onward, rather than the Apple II as Jobs does, as that’s where most of his current legacy is based. It always feels a little bit disingenuous when Jobs’ narratives focus on 1975-85, and that romantic rags-to-riches story, because Apple hasn’t been a startup for a really long time. For its part, The Man in the Machine feels grounded in reality, it feels comprehensive and well-researched. It also feels a little unbalanced, too eager to overcompensate for all the worship Jobs has received in films of yesteryear. But when former employees are shown on screen literally crying as they read a letter to the editor they wrote about Jobs on his passing, it seems to most documentarians the next question would have been, “Why are you crying?” Maybe Gibney’s obsession with “the machine” (both the beginning and the ending posit the question of why we’re so intimate with these mere objects) kept him from capturing the human story that’s very much a part of creating and using technology as well.