Warchus and Beresford have managed to sneak a progressive, rule-breaking film into mainstream cinemas. You'll be driven to tears, and every drop is earned.

Warchus and Beresford have managed to sneak a progressive, rule-breaking film into mainstream cinemas. You'll be driven to tears, and every drop is earned.

In the mid 1980s, thousands of British coal miners went on strike in reaction to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s vow to rid the U.K. of the National Union of Mineworkers, or NUM. After a hard-fought battle of walk-outs and picketing that occasionally descended into violence (three deaths were recorded), the miners were ultimately defeated by Thatcher’s regime. The damage to the mining community was devastating: Around the time of the strikes, there were 174 working mines. Today, there are only a handful, and many old mining villages have been reduced to veritable ghost towns, stricken with poverty and unemployment.

But there’s more to the story than that. There’s a silver lining that’s amplified and turned into a beacon of hope in Pride, a rousing, crowd-pleasing drama based on true events that proves the miners’ battle wasn’t fought in vein, thanks to the aid of some unlikely allies. You’ll be compelled to cheer and driven to tears, and the film earns every drop.

The focus is the forming of a shaky coalition: A group of young Londoners called Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), led by the uncompromising and charismatic Mark Ashton (Ben Schnetzer), extend a helping hand to the working-class strikers (LGSM views them as kindred spirits, as they too are being bullied and harassed by the heavy-handed police force). They hold buckets in the street, sending whatever they manage to scrounge up to the miners in hopes to aid in their losing battle.

The particular union they connect with is located in a village in South Wales, and following a visit from the union rep, Dai Donovan (Paddy Considine), Mark packs his activist friends into a brightly-decorated van and heads to the mining town to establish the newly formed partnership in person. Friction between the groups–stemming from the macho-minded miners’ skepticism and reluctance to accept LGSM’s help–inevitably arises, but inch by inch the two parties form a sturdy partnership.

At first glance, the plot’s trajectory may seem quite predictable or basic but, again, there’s more to the story than that. The extraordinary thing about Pride is that, underneath the mainstream presentation and heartstring-pulling manipulation (which never feels hokey, since it’s largely based in fact), it quietly expands the horizons of queer cinema: Gays are portrayed not as frail victims, but as powerful heroes and defenders, and they aren’t sexualized in the slightest (sex and romance are virtual non-factors). These subtle breaks from stereotype were designed by writer Stephen Beresford, who along with director Matthew Warchus have snuck a progressive, rule-breaking movie into mainstream cinemas.

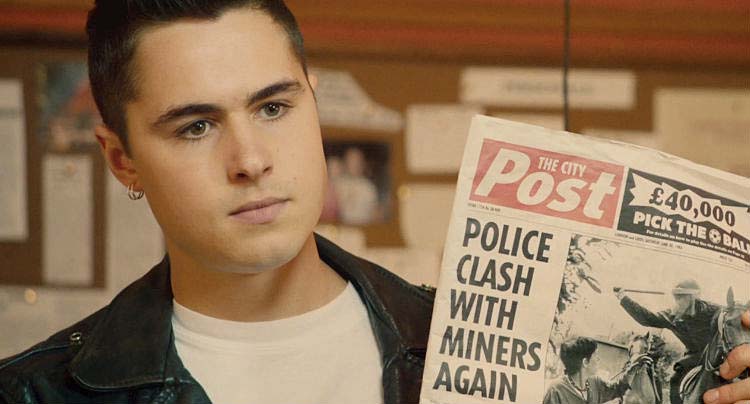

The film breaks a less socio-political convention in that it doesn’t have a central character. It’s a true ensemble piece, boasting an expansive roster of characters played by actors who maximize their on-screen minutes. Each character is alive and memorable, despite the brevity of their appearances. Vets Bill Nighy (playing the town’s good-hearted voice of reason) and Imelda Staunton (as an open-armed welcomer of the gay contingent) join Considine as union advocates of LGSM (all three will make you love them), while the LGSM crew is made up of similarly strong personalities. The Wire‘s Dominic West plays Jonathan Blake, a flamboyant partier who wins over some of the miners with his disco dance moves, while Andrew Scott plays his sheepish bookstore-owning partner Gethin. Fay Marsay is Steph, a punk-rock fireball who for a time is the only lesbian member of the group (she’s the “L” in LGSM, she says), who befriends Joe (George Mackay), a shy, sheltered college student who’s having the time of his life fighting for miner’s rights. Schnetzer, a relative newcomer, steals the show as the sole American cast member, pulling off a flawless Irish accent and exercising real dominance in his sleek leather jacket and sharp haircut.

Most of the film’s laughs stem from the older ladies’ blunt and open curiosity about the gay community: When they find a dildo underneath a bed during their visit to London, they laugh, scream, and convulse like giddy schoolgirls. Sometimes the jumps from pathos to comedy and back again feel a bit herky-jerky. Beresford has fashioned an incredibly dense script, of which the bumpy tonal shifts are likely symptomatic. But all in all, the sprawling nature of the story lends the film a sense of forward momentum, as Beresford’s thoughtful, organized plot construction keeps the myriad faces and events from feeling jumbled. Most of the heavier drama comes in the film’s final third, when the AIDS epidemic rears its ugly head and some of our LGSM friends are affected.

There’s only one clear villain to keep track of in the film, a homophobic miner’s widow (Lisa Palfrey) who tips off the tabloids to the union’s new supporters, resulting in a newspaper headline that reads, “Pits and Perverts”. Mark convinces his mates to embrace and hijack the insult, brainstorming an idea to hold a fund-raising concert back in London and call it–you guessed it–“Pits and Perverts”.

And it’s that philosophy of taking a bad thing and using positivity to flip it around that gives Pride its power. Yes, the mining community was all but ravaged following their hard defeat, but as Dai says in the film, “To find out you had a friend you never knew existed…well that’s the best feeling in the world.” In a time when even children’s films have to be sarcastic and snarky to draw money, it’s reassuring to see a feel-good film that unapologetically embraces hope and sentimentality. Even better, it’s good to see a film that, like its heroes, fights with heart and ingenuity to change people’s minds.