A crafty, refreshingly platonic take on young-adult fiction with an exuberant visual sensibility.

A crafty, refreshingly platonic take on young-adult fiction with an exuberant visual sensibility.

A particularly crafty young-adult tear-jerker, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl packs an emotional punch, but hits us with a looping left hook as opposed to its contemporaries’ straight jabs on the nose. Director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon and screenwriter Jesse Andrews (who adapted from his own novel) go to great lengths to assure us that this won’t be your typical teen drama. They’re setting a booby trap: while most of Me and Earl sidesteps convention, its endgame is familiar, designed to make you reach for the tissues and hug your loved ones a little tighter. I wouldn’t say I fell for the trap completely (for better or for worse, my eyes stayed dry throughout), but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t moved.

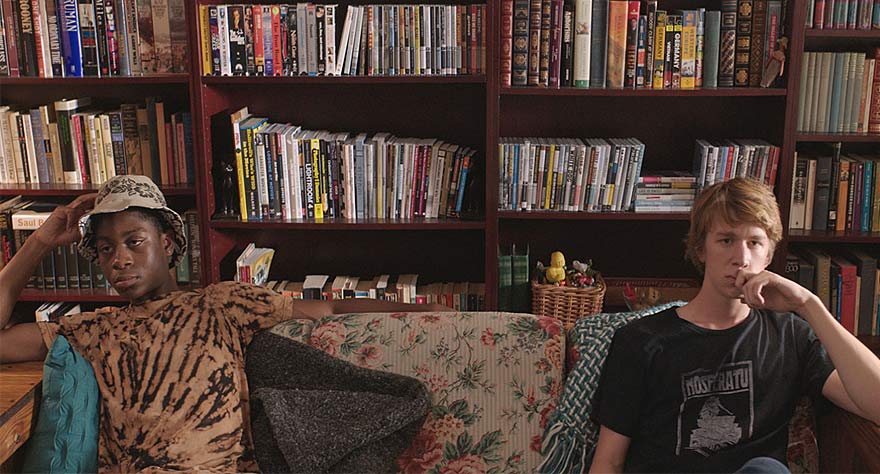

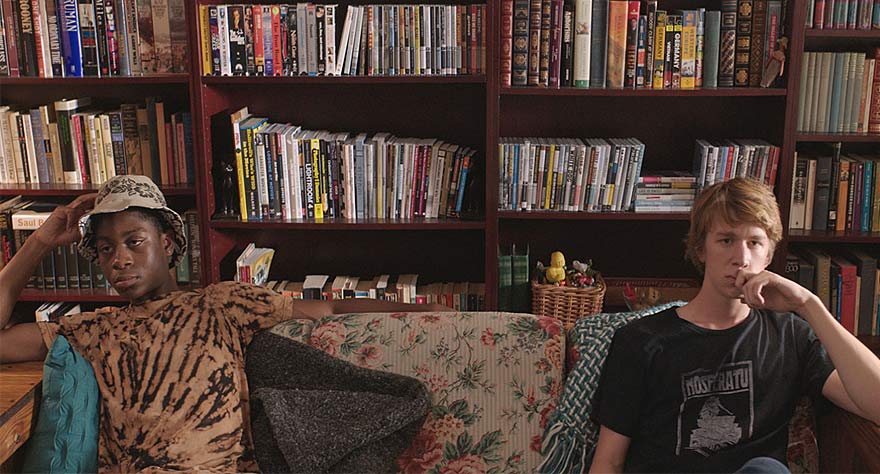

The film won the two biggest prizes at Sundance earlier this year, and I’ve got to believe part of its success at the festival lies in the “Me” of the film’s title. The main character, Greg (Thomas Mann), is walking catnip for film geeks. He’s a witty, socially faceless high-schooler who, on his spare time, makes DIY spoofs of Criterion Collection classics with his best bud, Earl (R.J. Cyler). (Their sizable oeuvre includes gems like The Rad Shoes, Eyes Wide Butt and La Gelee.)

The drama stems from Greg and Earl’s schoolmate Rachel (Olivia Cooke), the terminal teen from the title who’s been diagnosed with leukemia. Greg’s mom (Connie Britton, who played one of the greatest TV moms ever on Friday Night Lights), upon hearing of the girl’s condition, terrorizes him into the ridiculously awkward situation of befriending Rachel out of the blue. At the foot of Rachel’s staircase, Greg comes clean. “I’m actually here because my mom is making me,” he says with a shrug. “Just let me hang out with you for one day. I can tell my mom we hung out and then we can be out of each others’ lives. Deal?”

In that moment they do make a deal, but not the one Greg so awkwardly outlined. By Greg being so forthcoming and honest about his naggy-mom situation, he earns her trust. He says probably the only thing that would have compelled Rachel to invite him into her room, and from there they make an unspoken pact to never bullshit each other. The film revolves around their friendship, which is predicated on this “no-bullshit” pact, and when it’s broken, their friendship consequently breaks down.

The film’s quick-witted dialogue is mostly funny, though the smartass-ness can feel a little overbearing. Greg narrates, breaking the story up with wry road markers like “Day One of Doomed Friendship,” addressing us directly, a device that sets up most of the film’s frank subversions of YA clichés. In the first of many scenes involving Rachel and Greg hanging out in her elaborately hand-decorated bedroom, they make a real connection and lock eyes. Via narration and a quick visual flourish, Greg promises that this is a strictly platonic story, free of nervous sexual tension (between he and Rachel, at least). This is a smart move by Gomez-Rejon and Andrews, as it dispels any anticipation the audience may have of Greg and Rachel getting together. Without this little aside, the resulting “Are they gonna kiss?” thoughts of teen romance would have been a major distraction from the story, which is about something else entirely.

Top-to-bottom, the performers enrich the material, making moments and characterizations work when, on paper, they’re pretty sketchy. Earl, for example, falls into black-teen stereotype a little too much, but Cyler’s measured, steady-handed approach to acting give Earl gravitas and maturity that makes him a perfect counter-weight to Greg’s skittish self-defeatism and neurosis. Mann slouches and mumbles just like me and all my nerdy friends did in high school (I mean that as a compliment), and his performance is only outdone by Cooke’s. With every muscle in her face relaxed, she can convey a wide range of emotions, from fear, to frustration, to sadness, to forgiveness. When Greg’s social ineptness gets out of control, she just sits there like a sage, blank-faced, though through her eyes we know exactly what she’s thinking.

The adult characterizations aren’t appealing, though the actors embodying them are welcome presences all. Greg’s dad is played by Nick Offerman, and though he and Britton have little chemistry, his fleeting nudges of encouragement to his son feel sincere and warm. The most archetypal role is given to Jon Bernthal, who plays Greg and Earl’s favorite, tatted-up teacher (he’s Mr. Turner from Boy Meets World). Molly Shannon plays Rachel’s mom, whose not-so-subtle sexual advances on Greg drove me closer to tears than the film’s tragic elements. When she is called upon to hit dramatic beats, though, she overachieves.

The movie’s visuals are its strength; the camerawork and editing is dynamic, thoughtful and patient. Gomez-Rejon and DP Chung-hoon Chung use a lot of wide-angle shots and panning and flashy maneuvers that recall Wes Anderson and Martin Scorsese for sure, though I think Gomez-Rejon’s style is less polished and more spontaneous (the camera moves feel very choreographed, yet unpredictable). There’s a wonderful sense of movement and color to the visuals, though the filmmakers have enough discipline to know when to slow things down. A long, static, uninterrupted shot near the end of the film sees Greg and Rachel having a very heavy, very uncomfortable conversation, and the camera is almost cowering in the corner of the room. The actors will go 15-20 seconds without saying a word, and the tension in there is so thick that there’s no way the camera could ever wade through it or dare to budge. The film also harbors one of the best montages I’ve seen in a long time, one which cleverly illustrates the many emotional ups and downs of Greg and Rachel’s summertime meet-ups.

The Fault In Our Stars is a movie with a similar outer shell to Me and Earl, but with way more hanky-panky. That movie is about kids always saying the exact right thing or the exact wrong thing all the time, the filmmakers and actors banging on the drums of romance and tragedy as hard as they can the whole way through. Me and Earl feels much more frazzled and uncomfortable and authentic, frankly, taking a more low-key approach that’s a little easier to digest than full-on melodrama. What’s captured here so well is the solipsism and confusion of being an adolescent who’s forced to deal with death before you’re ready to, an aspect of life so many films have trouble representing on-screen. Gomez-Rejon and his three young leads have so much promise it’s scary.