An excellent cast and some touching moments make this schmaltzy crowd-pleaser easy to swallow.

An excellent cast and some touching moments make this schmaltzy crowd-pleaser easy to swallow.

When describing a film, words like “schmaltz” or “cliché” are typically reserved for derision, used to chastise a film for lazily indulging in stale familiarities instead of achieving something more natural or truthful. But sometimes schmaltzy clichés aren’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s paradoxical in some ways that a film’s use of clichés can make it feel artificial when clichés exist precisely because of their natural familiarity (in reality, it’s more about how they’re employed—rather than if they’re used at all). Last Cab to Darwin, Jeremy Sims’ latest feature, has all the markings of “been there, done that.” It’s a tale about a curmudgeonly old man who, through trying out new experiences, learns to appreciate his life and the people willing to have him in theirs. And for all the borderline cringeworthy moments of manufactured sentimentality peppered throughout Last Cab to Darwin, there are also plenty of warm, funny and entertaining examples of earning the right to indulge in the maudlin.

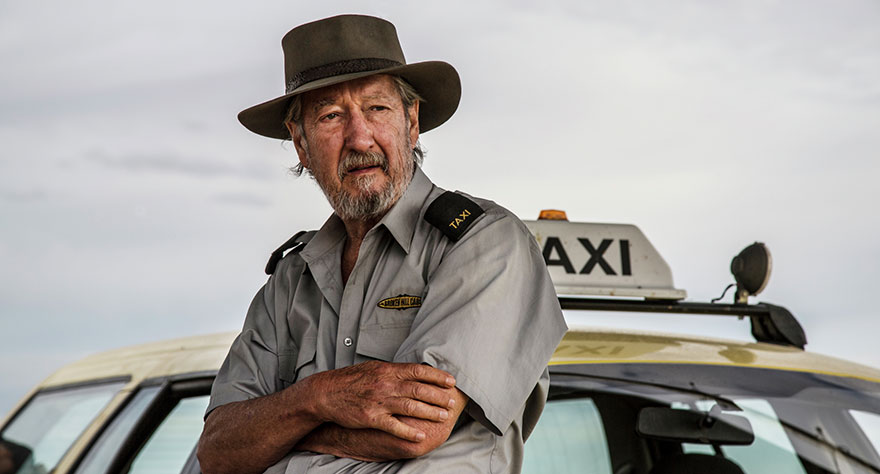

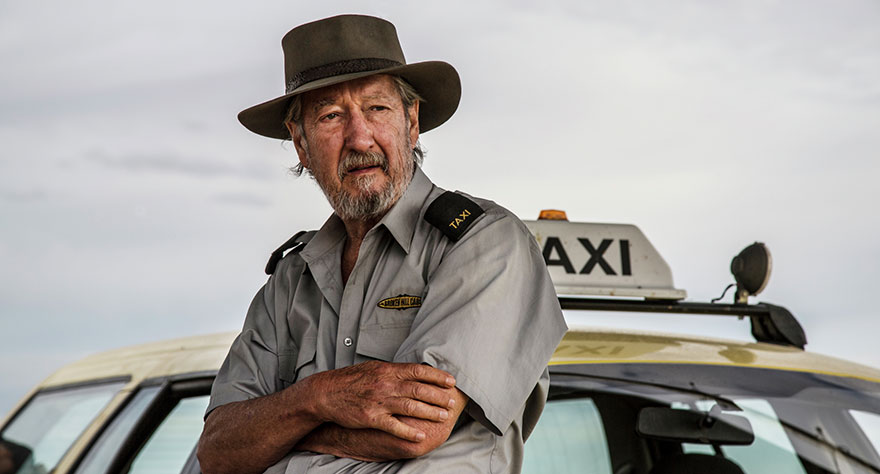

In the town of Broken Hill, cab driver Rex (Michael Caton) lives out a meager existence, his only true companion being his dog named Dog (“Rex was taken,” he says dryly when someone asks him about the name). He has a social life, but it’s kept at arm’s length, giving him the ability to retreat into solitude if he feels like it. He goes for drinks at the local bar with his friends from time to time and hides the occasionally romantic relationship he has with Aboriginal neighbour Polly (Ningali Lawford-Wolf). The opening goes a long way in establishing their diverting and charming chemistry: Rex comes outside in the morning to find Polly cursing him out at the top of her lungs for dumping his garbage in her bin, then brings over some tea for them to drink together while she cuddles up to Rex on his porch. Rex obviously has the potential for a great life, except he refuses to allow himself to have it.

Then the bad news hits: a trip to the doctor’s about Rex’s trouble keeping food down turns into a diagnosis of an aggressive form of stomach cancer, giving Rex 3 months to live. He stubbornly shuts down the possibility for treating his disease, insisting that he’ll continue driving his taxi until he can’t anymore. Then a form of hope arrives for the cynically-minded Rex: he learns that the Northern Territories of Australia recently legalized euthanasia, he sees a chance to die on his own terms. After contacting a doctor (Jacki Weaver) he sees in the newspaper to set up an appointment to die, she tells him that he would have to travel up north to Darwin in order to go through with the procedure. Rex decides to get in his cab and drive the entire 3,000 kilometre trip on his own, abandoning everyone in Broken Hill and leaving Polly his house, belongings, and Dog.

It doesn’t come as a surprise that, once Rex hits the road, Last Cab to Darwin transforms itself into a generic road movie. He drives along to various montages set to upbeat music, encounters ghost towns, meets eccentric locals, and hits different obstacles along the way (the usual hallmarks of a cross-country car ride). These sequences flow nicely within the film’s pacing, mainly thanks to the terrific cinematography by Steve Arnold (although, by this point, I’m thinking it’s difficult for anyone to film the Outback and make it not look spectacular) and Caton’s performance, who barely hides Rex’s vulnerability underneath his hard exterior. Caton transforms his character from an archetype to someone much more relatable and human as the film continues on and Rex begins opening up to those around him.

The same goes for Lawford-Wolf, who turns out to be the heart of the film as Polly. She’s a tough woman from the first moment we see her screaming at the top of her lungs, though Lawford-Wolf combats the harshness with a great amount of sensitivity once she lets down her guard. The screenplay, written by Sims and Reg Cribb (adapted from Cribb’s successful stage play), also goes out of its way to establish the still-rampant racism surrounding Polly, showing her hard-edged persona as something she does more out of survival than anything. The few moments when Rex calls Polly during his trip are by far the most heartbreaking and emotional moments, largely because of Lawford-Wolf’s fantastic performance. It’s the film’s saving grace from falling into a sappy mess.

But just as Last Cab to Darwin starts becoming one of the better feel-good tearjerkers in recent years, bad choices and preposterous developments come and sour the good vibes. As Rex makes his way up north to Darwin, he winds up taking on two passengers. The first is Tilly (Mark Coles Smith), a young Aboriginal man whose penchant for drinking and partying ruins his chances of becoming a professional footballer. Smith has plenty of charisma to make Tilly a likable guy despite his screwups (including neglecting his wife and kids), but he’s written as a broad caricature, the kind of wise slacker who likes to begin sentences with phrases like “Don’t you worry about me”, in the tone of a person who actually has it all figured out. And it’s not even a question about whether Tilly can actually play football. He claims he’s great—and he winds up being just that—but it takes Rex to eventually put him on the right path and shed his alcoholism before he lives up to his full potential. It’s a subplot that winds up feeling disappointingly slight, considering the amount of time spent with Tilly throughout.

Even more hilariously preposterous is a sequence where Rex and Tilly meet the bartender Julie (Emma Hamilton), a British girl who vaguely answers any questions about how she wound up in Australia. Later that night at the bar, Rex falls severely ill. While Julie tries to save him, her boss tells her to call an ambulance and get back to work. It’s at this moment that Julie reveals she’s actually a former nurse, an oh-so-convenient coincidence that winds up making her tag along for the ride as Rex’s caretaker. Other moments like this happen throughout: when Rex calls a radio show to talk about his illness earlier on in Broken Hill, the camera cuts to all of Rex’s friends across town who all happen to be listening in at the same time. These scenes serve as little reminders that, no matter pleasant the film may be, there’s a limit to the amount of BS one can pile on an audience.

The last act, where Rex arrives and Weaver’s character takes on a more prominent role, is a bit of a fumble, especially when the story turns to highlighting how Rex has changed those around him for the better. But a touching scene between Rex and Polly and a surprisingly low-key ending things on a note that’s more bittersweet than melancholy help turn things around a bit. There’s no denying that audiences will enjoy Sims’ film, laughing and crying at the exact moments it wants them to (there were plenty of tears and sniffling at my screening), but Sims having his heart in the right place can’t entirely mask the mawkish and cheesy nature of the story. Last Cab to Darwin, therefore, operates as a guide on how to do schmaltz right and wrong. It’s a ratio that tips over a little more on the wrong side, but the terrific performances and touching relationship at the centre of it all make this film a lot easier to swallow.