History is made behind the camera in this detached documentary about the world's first citizen journalists.

History is made behind the camera in this detached documentary about the world's first citizen journalists.

I’m hard-pressed to think of the last time something of historical significance happened and there wasn’t a camera around to record the event. I don’t mean a news camera; I mean the kind of camera anyone might have in their pocket at any given moment. The advent of video technology on mobile phones has created a culture where anything that happens can be recorded at a moment’s notice and distributed globally via social media. It’s not hard to recall the days when personal video cameras weren’t as readily available, or when they were the stuff of home movies, weddings, corporate training videos, and sex tapes. It wasn’t too long before that, though, video cameras weren’t even an option for personal use. Here Come the Videofreex, a documentary from co-directors Jon Nealon and Jenny Raskin, looks at the genesis of video cameras for personal use, and how two early owners of video equipment started something of a media revolution.

The film opens with a harrowing scene: a present-day team of gloved experts pores over boxes of videotapes that have fallen victim to mold. In some cases, spooled tape is sticking to itself, creating a sense of urgency that must be restrained for the safety of the tape. This brief scene is followed by title cards that offer all the prologue the documentary needs:

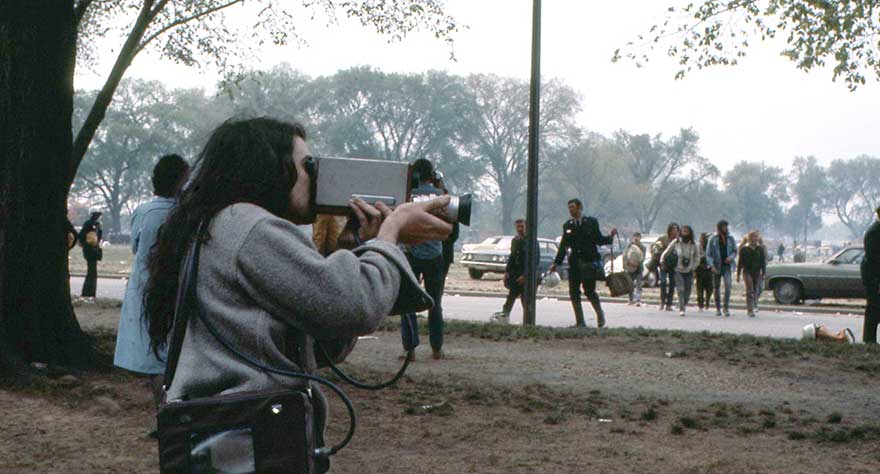

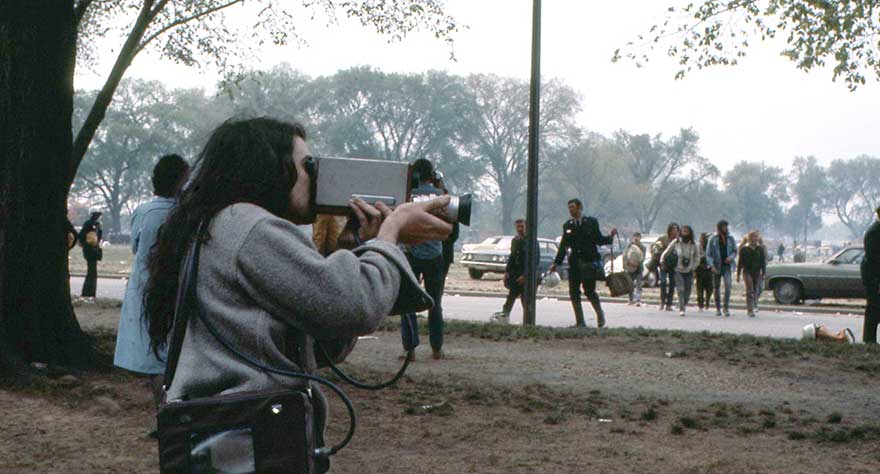

In 1968, Sony introduced the CV-2400 PortaPak, the first portable video camera. For the first time, it was possible to record picture and sound and play it back right away.

The story moves to 1969, when David Cort and Parry Teasdale, strangers who both acquired video cameras, met by chance at Woodstock, where both were more interested in filming everything going on except the music. A friendship was forged, a partnership began, and a name was coined. Before long, the duo would recruit eight others, land a gig with CBS, lose that gig with CBS, and go on to record seminal moments and legendary figures in US history.

Here Come the Videofreex, presented chronologically for the most part, is really a tale of two histories. The first history is that of the group itself. In addition to Cort and Teasdale, members included Skip Blumberg, Nancy Cain, Bart Friedman, Davidson Gigliotti, Chuck Kennedy, Mary Curtis Ratcliff, Carol Vontobel, and Ann Woodward. Each person had their own specialty, from editing to accounting, and each was treated as an equal member (that said, like any team, this one had its all-stars and its role-players, and those designations are implied here).

The second history is what the group recorded. Moments of modern US history where the Videofreex were present include discussions with Abbie Hoffman during the Trial of the Chicago Eight, an interview with soon-to-be-slain Black Panther Fred Hampton, a Women’s Strike for Equality, Anti-War Protests, and the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami. This treasure-trove of footage is not just history in the making, it’s history in the raw. In today’s media, between our cameras-are-everywhere existence and the slick packaging we are used to being fed from news outlets and websites, it’s easy to forget what it feels like to organically witness history because we’re so busy consuming what we’re being fed. This film is a great reminder of that feeling. The footage, presented in its original 4:3 aspect ratio, is slick in its native, almost sterile, black-and-white images. It’s also very effective that the present-day interviews with the talking-head surviving members of the Videofreex, while in color, are also in presented in 4:3.

But what the film is flush with in terms of footage, it lacks in engaging narrative. While there is plenty of history to be had, it all has a museum piece feel to it, as if the film isn’t really teaching anything, but rather putting everything on display to be admired. It’s history being shown, not history being shared. The filmmakers also seem to be so enamored by the footage they have, they think any footage is good footage. Nealon and Raskin use many clips that are nothing more than the Videofreex recording themselves and/or each other. It’s cute at first, but soon that footage takes on the feel of any other home videos found in most households in the 1980s.

As their tale winds to a close, the Videofreex again find themselves ahead of the new media curve. Fed up with New York and their inability to distribute their content, they move to a large farmhouse in the Catskills. It’s there that they curry favor with the suspicious locals by creating what will eventually be known as Cable Access Television. They even fancy themselves pirates of the airwaves, and while technically they are, it’s not as sexy as it sounds. The locals eat it up, but to watch the locals create and record cable access programming tests the patience more than actually watching cable access programming.

Here Come the Videofreex succeeds in telling a tale of how a two-person partnership became a ten-person collective, and how their efforts simultaneously made history and made them historians. The film also shows how anyone rolling video today, whether by camera or cameraphone, stands on the shoulders of that collective. It’s an important documentary about an important point in the timeline of American media and technology, even though its presentation struggles to connect with the viewer.

Here Come the Videofreex opens April 6th at The Royal Cinema in Toronto, Ontario.