Heavy subject matter is given a delicate touch, observing one woman's efforts to tackle human trafficking in Chicago.

Heavy subject matter is given a delicate touch, observing one woman's efforts to tackle human trafficking in Chicago.

Dreamcatcher, director Kim Longinotto’s documentary following one woman’s efforts to stop (or at least relieve the effects of) human trafficking, wastes no time hitting the streets of Chicago’s most dangerous neighborhoods.

A few minutes in, and we’re already sitting shotgun to the film’s heroine Brenda Myers-Powell and her partner Stephanie Daniels-Wilson, as they drive their van throughout town, giving a warm ear to working women who need to talk and condoms to those who aren’t quite ready. These stories get dire quick—one of the earliest stories comes from a woman who had been stabbed 19 times and lived to talk about it. She questions why her friends succumbed to their wounds, and yet here she is, living but not really living.

Brenda’s partner, another middle-age woman, offers the only nugget of hope: “When you get sick and tired of being sick and tired, you call us, and let us help.” The woman declines—and yet, as is often the case in this film, a sense of hope still lingers.

The reason why this film captures that unexpected redemptive spirit despite dealing with victims of the sex trade, many of whom are high-school aged, lies completely on the shoulders of the film’s star, Brenda. After 25 years on those same streets, a brutal attack left her literally skinned alive—she alludes to the reconstructive surgery to regain her “womanhood,” her face. She started The Dreamcatcher Foundation as a means to intervene in young women’s lives, allowing them the emotional—and when possible legal or financial—support they need to recover.

For people who follow the documentary format, the most obvious comparison Longinotto’s film will recall is A&E’s long-running docuseries Intervention. There are a few differences (other than the sort of addiction) that make this film a bit different from your run-of-the-mill hit-rock-bottom story—the most obvious is Brenda herself. I’ve seen a fair chunk of Intervention’s nine seasons, and purely as a viewer, I have to say, sometimes those interventions gone awry (the ones where the subjects turn volatile as they’re threatened with losing privileges like their home or financial support) made me feel squeamish. Is it effective? I’m not the one to say. But it must feel a bit degrading, even humiliating, and here I am watching this person lose all sense of autonomy from the comfort of my living room. Perhaps, the reason Dreamcatcher feels less hopeless is because Brenda’s methodology completely removes the shame factor. There is no timeline to say “yes.” She’s on these women’s side whether or not they seek help, and whether or not they relapse once they do. That sort of system seems more in touch with reality.

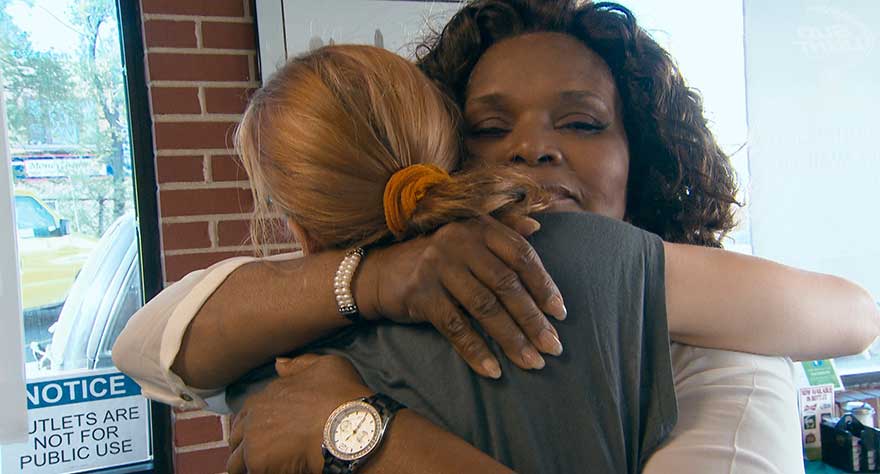

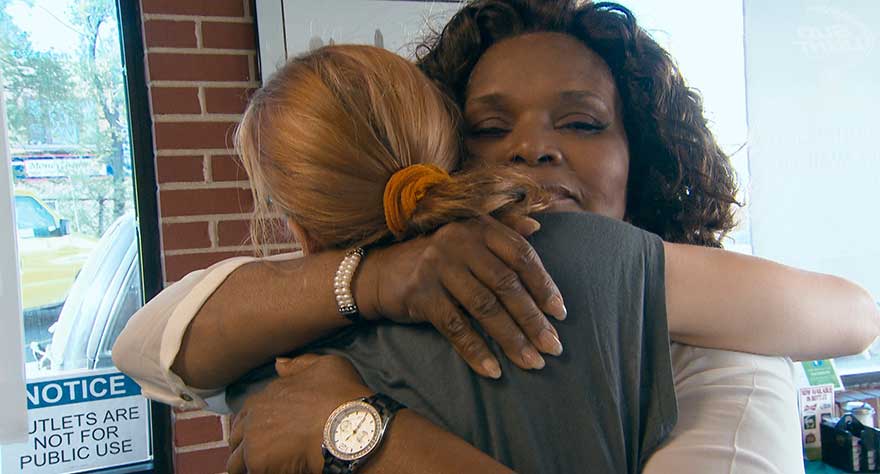

I could say this film has a lot of heart, but that’s an easy assessment to make about a film that takes on a worthwhile cause. Its true strength is that the filmmakers have found such an effective subject in Brenda—who is not just an inspiring person, but shines on screen with all the sass and attitude of a women who could be running her own talkshow, if she weren’t too busy using her words to save lives. Because she’s so effective at what she does, a lot of the film’s arguments are made without explicitly having to say them. Clearly, the strongest medicine a psychologically damaged young woman on the street can be given is another human being. That seems to beg the question, how do we get more state-sponsored versions of Brenda? Secondly, by the filmmakers smartly choosing to focus on the women and not the act (we never see these women in sexually compromising situations), we’re left to remember their humanity. This film, which is comprised entirely of group or one-on-one dialogues, is a montage of women articulating the full range of their emotions. My guess is that chance at self-awareness is not often allotted to many of these women. And it feels real. Brenda, being from the street herself, can talk colloquially, and the filmmakers technically match this on-the-ground approach. We don’t have any studio-lit, dramatic macro-shot interviews. The most touching scene, where Brenda has a bit of a breakdown in her car thinking about the time she’ll need to take away from the women during an upcoming surgery, feels like someone just talking to themselves in the rearview mirror. The film doesn’t pull any cinematic magic tricks to make this woman a hero—she already is one.

The end result is, yes, viewers will know more about The Dreamcatcher Foundation and its co-founder Brenda Myers-Powell, but I think they’ll develop a lot of compassion for the half dozen women at the center of the film as well. When Brenda allows a former pimp to talk at a conference in Las Vegas, she encourages the crowd to keep an open mind because knowledge is power. And maybe for legal reform, that’s what we need: A bit of information. A bit of skepticism about how much of a choice a life of prostitution really is. A curiosity as to whether our courts are trying victims as criminals. Obviously Brenda is one woman and this is just one film, but both have done a commendable job in starting a compelling conversation.