Heinzerlig manages to convey profoundly simple truths while refusing both cynicism and clear opposition in his portrayal of vastly different artists drawn together.

Heinzerlig manages to convey profoundly simple truths while refusing both cynicism and clear opposition in his portrayal of vastly different artists drawn together.

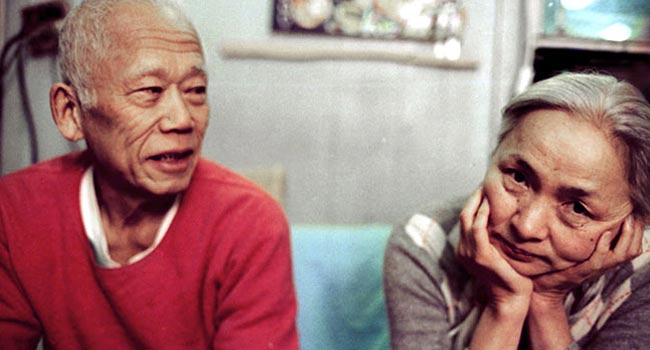

As a bracing, painfully honest look at the artistic temperament in its full kaleidoscopic nature, few films will come as close this year as Zachary Heinzerlig’s Cutie and the Boxer. Following the trials and tribulations of Japanese-born, New York-based ‘action’ painter Ushio Shinohara (the ‘Boxer’ in question, owing to his dipping fists in paint and punching to apply layers of abstract colour to his huge canvases), this efficiently-made documentary is by turns subtly powerful and deeply sad, given our introduction to the counterpoint to Ushio’s ‘genius:’ unflailing Noriko, wife and lifetime supporter and carer. When the action opens we’re witnessing the couple well into their twilight years (Ushio is an Octogenerian and Noriko late into her 60s), in a makeshift and far from glamorous New York loft and studio, still living with an air of bohemian spontaneity but at least, it seems, content.

Far from content, though, is director Heinzerlig with just crafting a hagiography of The Artist for that more obscure Lennon-Ono you probably haven’t heard of. With a whimsical contrast in style, Heinzerlig opts for hand-drawn animation to delve into the troubled shared past of Ushio and Noriko. He was almost 40, eccentric, ambitious and wild, and successful in his homeland before making a cocksure move to Manhattan; she 19, a starstruck art student with well-to-do parents that kept her afloat while she fell in love under guise of working towards her qualification. When that fell through, Ushio and Noriko were left to fend for themselves financially over the tumultuous next four decades which saw Ushio fall into bouts of Alcoholism, wavering between bursts of passionate creation and an nihilistic outlook toward his art. Meanwhile, Noriko effectively gave up her own career to absorb Ushio’s turbulent changes of affect, alternating moments of self-aggrandizing Ego with moments demonstrative of the generous, infectious love she was drawn to all those years ago.

The animation affords Cutie and the Boxer a sense of undeveloped, childlike immediacy in sentiment that is key to the emotional effectiveness of the film as a whole. In the same way that Isao Takahata’s animated Grave of the Fireflies (1988) employed the medium as a buffer between a difficult and in many ways traumatic subject matter and having an audience understand those feelings without being subject to direct re-enactment, Cutie and the Boxer too frames Noriko’s silent suffering in ways that alarm with their simplicity but achieve their impact precisely because of it. We begin these sequences unsure if the narrator is the director Heinzerlig or Noriko herself, but as her own work burgeons because of (or perhaps in spite of) all the attention paid to Ushio, we slowly realise we are witnessing the liberation of an individual, highly singular artist in her own right. Noriko’s meticulously drawn cartoons are full of the narrative, repressed feeling and labored-after, thought-about technique that the work of her husband can be argued to ‘lack’. If his art is about an essential kinetic energy and iterative, impulsive aesthetic judgments through the layers of abstraction, the two exhibited in tandem could not provide a greater material and philosophical contrast.

A combined show of this kind is precisely what Heinzerling works towards as the climactic moment of the documentary. No doubt the issue of artistic and creative competition among the couple is prevalent, providing dramatic tension, but Henzerlig’s generosity in his shaping of the film is in not leaving this a clear, clean, black and white dynamic. Regret and resentment form only smaller parts of a more complex relationship that marries the petty with the intangibles that form the bonds of long love. When we watch the reactions of these parents to their son Alex – who, we learn, is very much his Father’s Son in temperament – there is an inimitable sense of true failed opportunity, a sense of loss, but not of fingerpointing between the couple, and through it all a humanity shines through in the acceptance of whatever shortfalls he might have, and an ability to support him through it: to love, anyway. In this freely structured but both intimate and impartial document of the artist as a persona, it’s a reflection of the extraordinarily elastic relationship his parents share with each other — one that, I suspect (and perhaps Heinzerling is offering) is not so uncommon or extraordinary at all.