What it lacks in filmmaking acumen, is more than made up for in the wonder captured on film.

What it lacks in filmmaking acumen, is more than made up for in the wonder captured on film.

If you listen to enough random music on the radio or the internet, you are likely to hear a song you haven’t heard in a long time. The opening strains or rousing chorus of a tune that moved you in your youth can suddenly move you again, sometimes in a way you haven’t felt since oh-so long ago. Surely you have at least one song or one artist that takes you back to a happy place.

That concept — music tapping into something sudden and emotional, something visceral and positive — is being applied to elderly Alzheimer’s and dementia patients with startling results. How this came to be, and the path it has taken, is the subject of the 2014 Sundance Audience Prize winner for Best Documentary, Michael Rossato-Bennett’s Alive Inside.

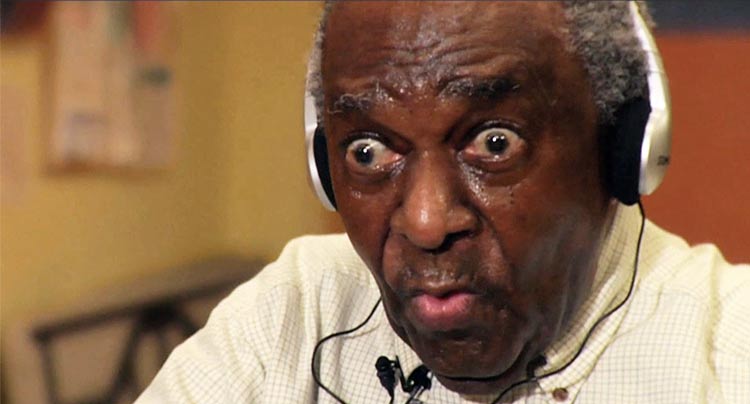

The story begins as many of these things do — by chance. When social worker Dan Cohen placed headphones on elderly Henry and played Henry’s favorite music from his youth, Dan noticed a miraculous change. Henry, who was once slouched in his seat, chronically lethargic, and completely disengaged from those around him, perked up. He changed his posture, danced in his seat, and even sang along to the music. This prompted Dan to invite Rossato-Bennett to spend the day with him and film Henry. Rossato-Bennett stuck around for three years. Over the course of that time, countless patients responded the way Henry did — with newfound energy and long-lost focus.

Alive Inside is an emotional triumph. From the first time Henry’s eyes grow wide as Cab Calloway wails through his headphones, and through the course of the film’s lean 73-minute running time, smiling is inevitable. Smiling at Bill, who is frustrated by his own inability to express the anger he feels inside, yet who is instantly soothed by The Shirelles’ “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.” Smiling at Denise, a bipolar schizophrenic who demands Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” yet who abandons her walker when music with a Latin flair plays. The names and faces and music change, but the smiles never end.

The film is rich with people like this, and while you might not know them personally, you know them for who they represent: your parents and your grandparents and your great-grandparents. And to see a spark in their eyes — a spark that hasn’t been seen there in years (if not decades) — is something joyful to behold again and again.

Yet for as much as Alive Inside tells this glorious tale of these once-lively people with spirit thought lost forever, only to be born again by the power of music, it is still a documentary, and as documentaries go, it’s a flawed victim of its own vagueness.

It offers little-to-no background information on its subjects, specifically when it comes to the music that stimulates them. Beyond basic information like favorite artist or favorite song, there is no understanding of why such a strong connection is made, or why these people react the way they do, to a particular song/artist. Cohen and Rossato-Bennett go to lengths to illustrate that playlists are customized, but with no understanding of why.

The film is also light on the bigger picture. Mental afflictions are explained, the reasons why music can have this effect are spoken to, and medical talking heads talk, but the subjects in the doc are only ever viewed in the moment. There is no long-game here, no consideration of what extended exposure to music can do for these people. There’s even a golden opportunity to understand the pros and cons of a long game when Rossato-Bennett presents a couple – Norman and Nell – who have lived happily in their own home for 10 years with Nell’s condition because of external stimulation like music. Nothing about them is deeply explored; they are merely poster examples. Ultimately, Rossato-Bennett and Cohen were at this for three years and yet nothing is known about the patients over that length of time other than their immediate responses.

Fundraising efforts and political actions are briefly covered, but there is nothing in-depth enough to fully appreciate the struggle Cohen endures to get music into nursing homes. Statistics of how many homes have a music program are presented at the end of the film, but entirely without context of effort .

What Alive Inside has plenty of, though, are barbs hurled at assisted living facilities, the hospital model they follow, and the medicine they practice, all without significant substantiation. There’s an argument to be made that the current model can be improved or that “just give them drugs” isn’t necessarily the best treatment approach, but rather than look at intricacies, Rossato-Bennett instead frames The System as the boogeyman – that thing responsible for the plight of these people he is rescuing. With only 73 minutes on film, Alive Inside would benefit from some extra time to make a better argument instead of making accusations.

Michael Rossato-Bennett is a first time documentarian and it shows. But what he lacks in filmmaking acumen, he more than makes up for in the wonder he has captured on film. He might not be deft enough to make a clearer case, but he’s smart enough to know what works on film. Watching parents and grandparents and great-grandparents so viscerally respond to music is like watching children discover a bounty under the tree on Christmas morning, and it is just as glorious. These scenes alone – scenes that are plentiful and demand your widest smiles – are worth the price of admission.