TIFF, Technicolor, and The Archers in Three, Two, One

The Dreaming In Technicolor film showcase at the TIFF Bell Lightbox continues in July with a trio of films made by a pair of directors who are singularly known for their breathtaking use of Technicolor. This use is not limited to just the visual palate, though. Co-directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger—collectively known as The Archers—take color further by using it as a critical storytelling element.

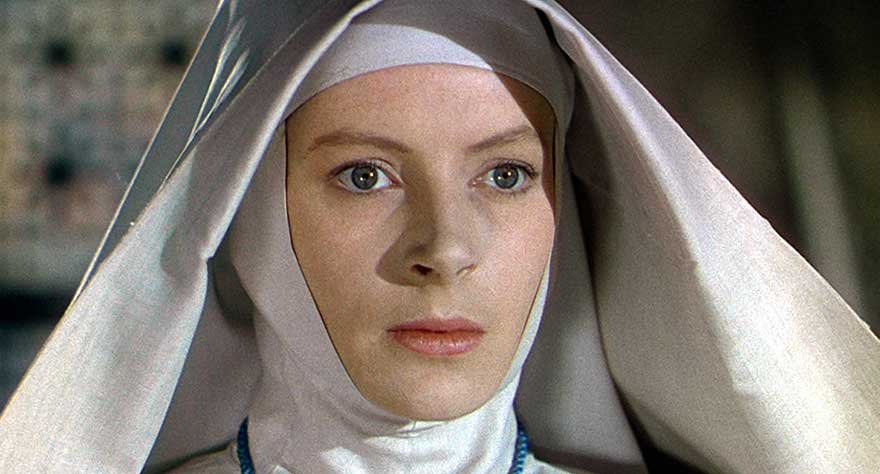

This is most evident in 1947’s Black Narcissus (screening July 7). The film centers on Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), a schoolteacher and member of the devout Order of the Servants of Mary, who has been chosen to head a new nunnery high in the Himalayan mountains. She and other nuns will provide medical care and education to the locals. When Sister Clodagh and her team, including the troubled Sister Ruth (the sensational Kathleen Byron) reach their destination, they establish their convent, medical facility, and school in the Palace of Mopu, a grand structure donated to them by the Old General (Esmond Knight), the local man of power and affluence. They get much-needed assistance from the Old General’s agent Mr. Dean (David Farrar), a rugged and handsome man as wise in the ways of man as the nuns are wise in the ways of God. Not long after they arrive, Sister Clodagh, Sister Ruth, and the other nuns find themselves in situations for which they are not prepared, including wavering faith, carnal temptations, and spiraling madness.

As is the case the with all great films, it isn’t what’s on the surface that is so impressive, it’s what’s beneath, and Black Narcissus has plenty going on beneath. That said, the surface of this gorgeous film cannot be ignored. Just as great noir films maximize shadows and light to set a nefarious mood, Black Narcissus maximizes vibrant, breathtaking Technicolor not to set a mood, but to set and maintain the backdrop for the contrast and conflict humming throughout.

Those contrasts and conflicts range from denominations of faith to the coexistence of the chaste and the sinful, but the most obvious is the stark whiteness of the nuns’ habits against the rich greens and other vibrantly tinted local fauna. The sisters move about like holy spirits in this lush and colorful environment. This contrast then extends beyond cloth vs. clover and becomes skin deep, as the nuns from the west literally pale in comparison to the darker-skinned locals of the South Asian mountain range. The rich color is a constant, almost hostile reminder of the secular life the nuns left behind, and as the story progresses, they find their faith wavering in different ways. The most impacted sister is Ruth, who spirals into sexual madness when she thinks Mr. Dean has a physical interest in her, and whose individual color palate changes as her psyche further devolves.

In an era when the Academy differentiated color from black and white films when crowning winners certain categories, Black Narcissus took home two Oscars: Best Cinematography, Color (Jack Cardiff) and Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Color (Alfred Junge).

The second film from The Archers on TIFF’s Technicolor slate is 1948’s The Red Shoes (screening July 11). Unlike the humble characters of Black Narcissus, this film’s leads yearn for fame in the world of ballet. Still, thematic similarities between the two are present, along with that gorgeous palate.

Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook) is the director of the world-class troupe Ballet Lermontov. Among the hundreds in attendance at his latest production are aspiring composer Julian Craster (Marius Goring) and aspiring dancer Victoria Page (Moira Shearer). Julian and Victoria both earn a spot on Lermontov’s roster, crossing paths only as a matter of professional happenstance. Then Lermontov chooses Craster to compose the score for, and Page to dance the lead in, his next great production: “The Ballet of the Red Shoes.” The production is a smash, and as Craster and Page rocket to stardom, they find time to find love, something that Lermontov vehemently opposes for several reasons. Craster and Page must find a way to make their love succeed under such demanding conditions.

The Red Shoes plays very much like many other “making it in show business” films from eras before and since, like 42nd Street (1933) and That Thing You Do! (1996). It opens with struggling rookies who work hard, pay their dues, and finally make it big until they take the wrong step, as so many in showbiz do. What sets The Red Shoes apart from its contemporaries are three things. The first is the psychological aspect, and how competing pressures considerably affect the mental wherewithal of the leads. (This is also the element that makes it a terrific companion piece to Black Narcissus).

Second is the glorious Technicolor palate. While the overall visuals of The Red Shoes are still exponentially more lush than anything Hollywood has to offer today, the film veers from using color as a broad contrast (a la Black Narcissus) and instead uses it with laser focus once “The Ballet of the Red Shoes” is introduced (along with other accent uses of the color red best enjoyed on multiple viewings).

Third, there is a 15-minute ballet segment in the middle of the film that is like nothing I’ve seen before. What makes it so grand is not just the beauty of it all (particularly Shearer’s performance), but the fact the segment is used to delve into Page’s psyche. There is a connection between the film’s story and the ballet’s story (based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale of the same title), and The Archers’ filmmaking here achieves another level. They manage to seamlessly incorporate a balletic adaptation of the same the story the film itself is based on, as well as make the ballet relevant to the film. If M.C. Escher had ever made a movie, this would have been it.

Like Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes walked home with two Oscars: Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Color (Hein Heckroth and Arthur Lawson) and Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture (Brian Easdale). It was also nominated in three other categories: Best Picture, Best Writing Motion Picture Story (Emeric Pressburger), and Best Film Editing (Reginald Mills).

Rounding out the trio is The Tales of Hoffmann, a film adaptation of the Jacques Offenbach opera of the same name. In both structure and execution, it is nothing like the other two films. Structurally, it has a clearly defined prologue, three independent yet interconnected stories, and an epilogue. Each story, all as told by Hoffmann (Robert Rounseville), is a fantastical tale of love and heartbreak. The first story features The Red Shoes star Moira Shearer (who also appears in the prologue and epilogue as a different character) as a scientific creation; the second features Ludmilla Tchérina as a courtesan; and the third features Ann Ayars as a sickly soprano. From an executional perspective, the film is an opera and is entirely sung. However, only Rounseville and Ayars sing their own parts; everyone else had someone sing for them.

Despite these differences, The Tales of Hoffmann still bears the trademark Archers color palate, with each story assigned its own unique primary hue. It also bears a great similarity in terms of setting scenes to music. The Archers dabble in this during the climax of Black Narcissus, and take it one step further with the 15-minute ballet production in The Red Shoes. This connection in particular makes it a strong choice to round out the trio.

The Tales of Hoffman, which won no Oscars but was nominated for two—Hein Heckroth for both Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Color; and Best Costume Design, Color—screens at TIFF on July 12.