Hot Docs 2014: I Am Big Bird, Private Violence, Mateo, Portrait of Jason

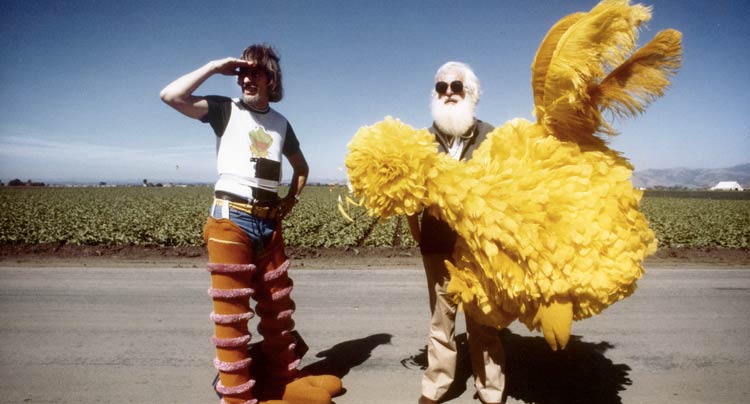

I Am Big Bird

I Am Big Bird is, not surprisingly, one of the more popular titles at the festival this year. Directors Dave LaMattina and Chad Walker tell the life story of Carroll Spinney, the man behind Big Bird and Oscar The Grouch. Spinney’s story is quite interesting, from his childhood goal to become a puppeteer to his hiring on Sesame Street and loving marriage to his second wife Deb. The problem is that LaMattina and Walker refuse to let Spinney’s story breathe for a single moment, instead relying on a barrage of maudlin tactics to choke tears out of viewers. This includes a loud, obnoxious, seemingly never-ending score, and incredibly manipulative editing choices.

LaMattina and Walker’s lack of confidence in their material is disappointing because Spinney’s story is definitely worthy of a documentary. Carroll and Deb’s love story is touching when they explain it, and when the film steps back it’s much better at getting an emotional response (a clip of Spinney, dressed up as Big Bird, singing “Bein’ Green” at Jim Henson’s memorial while choking back tears is the film’s only truly moving moment because the clip plays without any editing or interruptions). LaMattina and Walker’s heavy-handedness kills any chance of Spinney getting any kind of proper treatment, making I Am Big Bird a puff piece more than a documentary. The absurd praise thrown on Spinney and his family reaches nauseating heights by the end, with suggestions of their politeness helping another family move on from a tragic death along with contributing to Barack Obama’s election win in 2012 (!). Spinney’s life deserves more than this mawkish treatment.

Private Violence

HBO has good, effective documentaries down to a science by now, and Private Violence is yet another example of it. Director Cynthia Hill gives a vérité look into two lives: Kit Gruelle, a former victim of domestic abuse advocating for justice, and Deanna Walters, a mother trying to put away her abusive husband for good. Hill’s intent is to show the complexity with abusive relationships, and to explain why telling a victim of abuse to “Just leave” does more harm than good. Hill nails this aspect 100%, but the lack of any serious legal consequences for abuse is one of the most shocking parts of the film. Walters, who was driven across the country by her husband in his 18-wheeler and mercilessly beaten for days, is fighting to get him convicted for kidnapping and not for the abuse. Kidnapping is a felony and can get him put away for over 20 years; assault of a female is a misdemeanor and can only get him a maximum sentence of 150 days.

Hill cuts back and forth between Gruelle’s advocacy efforts and Walters’ attempt to move on, and the result is effective in its (somewhat) narrow focus. Walters’ case is used as a main symbol of the systemic problems of dealing with domestic abuse, while Gruelle’s visits of other victims paints a bigger picture of how widespread the issue is. Granted, Hill’s film will come across as a boilerplate social issue documentary to some, but her work is still powerful and informative. HBO’s involvement will most likely increase the film’s popularity, and as Private Violence shows this kind of subject matter needs to be looked at.

Mateo

Matthew Stoneman had dreams of becoming a pop star, until he went to prison for four years in 1997. Stoneman became obsessed with mariachi music and learned Spanish during his time in prison, coming out of jail reborn as a “Gringo Mariachi.” Matthew, who now goes by Mateo, repeatedly flies to Cuba so he can make a new album of songs inspired by the music scene in 1950s Havana.

Despite the four year journey director Aaron I. Naar took to make Mateo, there will be inevitable comparisons with Searching for Sugar Man. Both have an element of discovering a musical treasure (it’s not my kind of music, but Mateo actually is pretty good as a singer/songwriter), and that alone makes Mateo mostly enjoyable. Naar ends up surprisingly carving out a complex portrait of the white Spanish singer, whose life seems split into two halves. In Los Angeles he lives the solitary life of a hoarder, mostly going to different gigs so he can fund his trips to Havana. In Cuba, Mateo shows himself as quite the sociable person, even if his affinity for prostitutes can get very creepy.

Naar doesn’t come down on either side of his subject, a smart decision elevating Mateo beyond the “Gringo Mariachi” hook. Naar’s doc does flounder around the middle, as scenes of Mateo in Havana begin feeling repetitious, but a neat epilogue of sorts in Tokyo adds another fresh layer to the proceedings. Mateo won’t do much for an average viewer, but those interested in the subject matter will find themselves having a good time with it.

Portrait of Jason

Finally, a few words on Shirley Clarke’s landmark documentary Portrait of Jason. Hot Docs has a nice retrospective program, and this year they snagged the 35mm restoration of this 1967 classic. Over one night, Clarke filmed Jason Holliday, a charismatic hustler with plenty of stories to tell. From frame one, Portrait of Jason shows its awareness as a documentary with some layer of artifice. The image is out of focus, we hear the crew talking in the background, and Jason repeats the same line twice (“My name is Jason Holliday”) before admitting it’s a fake name.

Looking for “reality” in Portrait of Jason is a fool’s errand. Clarke and her crew, never seen but frequently heard, keep asking Jason to tell different stories (“Tell the one about the cop”). The film feels less like a profile or interview than people asking for Holliday’s greatest hits. Jason performs for the camera, delivering his stories with plenty of bravado and exaggerations. Attempts to dig deeper into his life show signs of a troubled childhood, but even stories of Jason getting abused by his father are told in the same overdramatic style.

Watching Portrait of Jason soon becomes an exhaustive, but necessary, experience. The questions will keep flying: How much of this is rehearsed? Is Jason telling the truth? Does he know what Clarke and her crew are going to do? That core question of what’s “real” never gets answered, making the film exist in a space of nothing but a series of subjective points of view. Clarke’s involvement of herself (many scenes end with the a black screen, while Clarke says to keep recording sound despite the reel ending) throws things into more chaos, as the expectation of her authorial hand providing some kind of grounding for the view goes out the window.

This approach will frustrate people (there were more than a few walkouts at the screening), but the questions Clarke’s film brings up are necessary reminders of the level of trust audiences give documentary filmmakers. The ethical qualities of Portrait of Jason continue to get blurred, with Clarke giving him more liquor as the night goes on and, by the final reel, openly attacking him to provoke some sort of response that fits their definition of something genuine (“Be honest, motherfucker, stop acting.”). There’s plenty to dissect in Portrait of Jason, something I don’t have the room for here (and better people have done excellent jobs already), but this is vital viewing for anyone who considers themselves a fan of documentaries.