2013 CAAMFest: Late Summer, When Night Falls, High Tech Low Life

Late Summer

Late Summer borrows its title from the work of one of the most celebrated directors of all time, Yasujiro Ozu. If you’re familiar with Ozu’s work, you’ll recognize that the title makes quite the statement. Surely director Ernie Park isn’t hoping to match the near cinematic perfection of Ozu’s family-drama masterpieces (Late Spring, Early Summer, etc.), is he? The answer is no, he is not so bold. Late Summer is a humble, tasteful love letter to the late, great auteur from an avid and educated appreciator of his work. He plays with several of Ozu’s signature techniques without abusing them; he merely gives them a knowing and appreciative nod. Park takes Ozu’s distinctly Eastern style of storytelling and injects it into a distinctly Western setting; an artsy black community in Nashville Tennessee to be exact. What’s remarkable is that it’s an Asian story set in the West; a look at an American family from the perspective of world cinema.

Though the setting is brand new, the story here is familiar Ozu territory. Nadia is a high school grad who lives with her single mother who she has depended on her whole life. Lately, everybody is pressuring Nadia to leave Nashville to go to college, but she is stubbornly resistant to the idea, wanting nothing but to stay with her mother and keep things the way they are. The thought of abandoning her mom saddens her deeply, but the people around her—including her mother—constantly push the reality that it’s time for her to move on to the next stage of her life.

Those familiar with Ozu’s work will recognize many of the techniques and themes utilized by Park. The film is composed entirely of static, quiet, serene shots of occupied an unoccupied spaces. Form is the focus here, though Park isn’t as meticulous about his composition as Ozu, nor is he trying to be (the film was shot in ten days.) The dialog, acting, and flow of the film are very much taken from Eastern cinema, which makes for a unique and refreshing portrayal of Nashville, one devoid of stereotypes. Park’s determined avoidance of tropes can be a little distracting at times, but that’s mostly a testament to how Western cinema has conditioned us to see Nashville as one thing only. Late Summer is a great example of what Asian American cinema can be.

RATING: 8.5

When Night Falls

It’s difficult to convey the crippling weight of death cinematically, as a large part of what makes the thought of it so unbearable is the torturously slow passage of time. In When Night Falls, director Ying Liang captures the way death permeates every moment of our lives when all hope is lost. In 2008, Yang Jia, a young man who believed he was wrongfully accused of theft and abused during the interrogation process, walked into a police station and murdered six officers, stabbing them repeatedly with a knife. Yang was sentenced to death. When Night Falls is a fictionalized account of Yang’s mother, Wang Jingmei’s dark, lonely search for justice for her son during his trail. It’s an intrepid and appropriately challenging piece of cinema that has no aim to entertain.

Nai An plays Wang with resounding gravitas. A minutes-long shot in which she rips days off of a calendar in a despairing trance is a riveting. The movie is almost entirely comprised of long, uneventful shots like this, like a morbid version of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman. The function of the constant lingering is to make us feel the gravity and misery that has poisoned Wang’s world. To watch her sit in her son’s now vacant bedroom staring at his bed that will never be used again is overwhelmingly depressing. There’s a dark cloud of hopelessness hanging over every frame of When Night Falls, and it isn’t likely to be an enjoyable or even tolerable experience for most, mostly due to its snail pace. It is, however, a significant artistic meditation on morality and loss that will probably leave you in desperate need of a pick-me-up.

RATING: 7

High Tech, Low Life

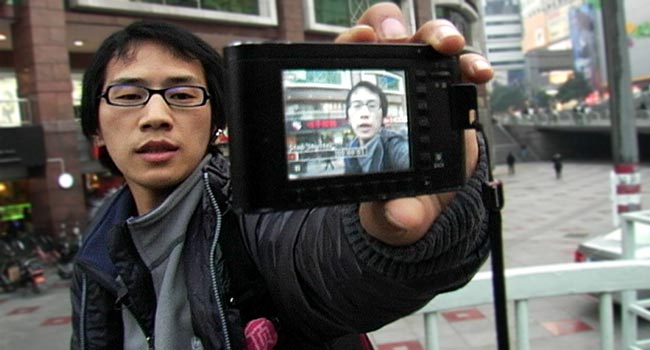

The People’s Republic of China’s extensive suppression of the internet in the country—which is unmatched by any other country in the world—is often referred to as “The Great Firewall.” High Tech, Low Life follows the lives of two bloggers—Zola and Tiger Temple—in their pursuit of the truth, in spite of the PRC’s restrictions. Zola is the more rebellious of the two, a young man who lives to attract attention through the broadcasting of the (sometimes ugly) truth. On his popular blog, he posted a photo of himself jumping over the Great Wall of China as a defiant middle finger to the PRC’s censorship. Tiger Temple is middle-aged, calm, and more activist than agitator. He posts videos of farmers who express how they have felt neglected by the Chinese government for years, giving them a voice they never had.

There is a large, intriguing David-and-Goliath story going on here that deserves to be the focus of Stephen Maing’s High Tech, Low Life. Unfortunately, Maing chooses instead to zoom in way too close, focusing on the quirky lives of his protagonists and in doing so fails to convey the magnitude and implications of their endeavors. There is a big lack of social and political context here, which reduces this film to being a documentary about two fairly interesting people and their daily lives. There are plenty of other docs like this, and it’s a shame that the storyline that should make this film unique is so downplayed.

RATING: 5.2