5 Must See Films Playing at the 2014 imagineNATIVE Festival

The world’s largest indigenous festival, imagineNATIVE showcases a wide variety of film, radio and media from Indigenous artists around the world. Now in its 15th year, the festival has brought an impressive selection of feature films to its line-up.

With the festival running between October 22 and 26, we wanted to let readers know some of the features worth checking out, especially since some screenings might be the only opportunity to catch some truly compelling films and stories in theatres. Be sure to read our thoughts below on our favourite films playing at imagineNATIVE, and check out the full line-up and schedule at www.imaginenative.org.

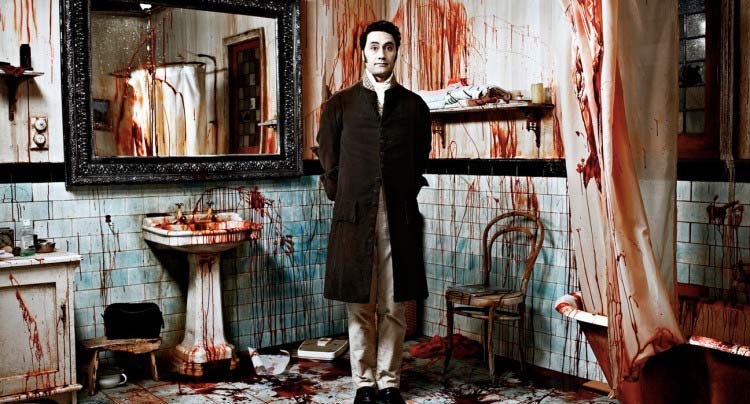

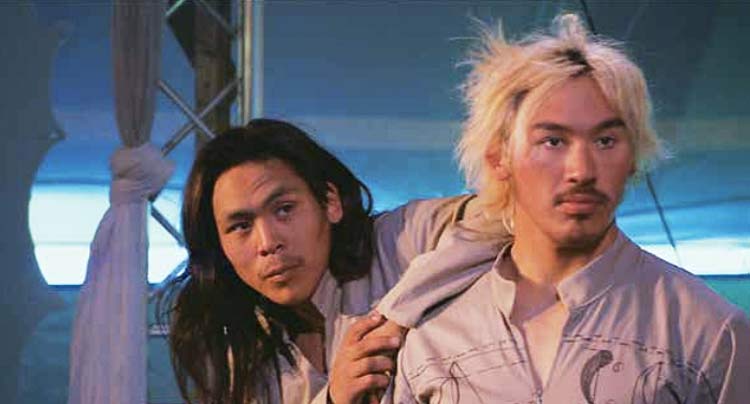

What We Do in the Shadows

Screens October 22 at 7pm (Opening Night Gala)

What We Do in the Shadows might have arrived late to the party (the vampire craze sparked by Twilight already reached its peak a while ago), but in this case it’s better late than never. Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi first conceived their film back in 2005 as a short, only to wait over 8 years before developing it into a feature. It’s a mockumentary following four vampires living together in New Zealand: stuck-up Viago (Waititi), ladies man Vladislav (Clement), “bad boy” Deacon (Jonathan Brugh) and 8000-year-old Peter, a Nosferatu-looking vampire who spends most of his time butchering people or sleeping in his tomb in the basement.

Kudos to Clement and Waititi for making such a funny film, especially since they are performing multiple variations of the same joke. What We Do in the Shadows mostly spends its time focusing on the way supernatural beings adapt to the kind of everyday banalities everyone else goes through. It’s a surprisingly adaptable joke, and whether it’s arguing over who’s slacking on their chores (“You have not done the dishes for five years!”) or trying to get invited into the city’s most popular nightclubs, it never stops being funny. That’s largely due to the hilarious cast, all of whom improvised their lines. Clement and Waititi wrote a script as the basis for the film, but the rest of the cast never saw any of their writing. It took over a year for the two of them to cut down over 100 hours of footage into a lean 90 minutes.

What We Do in the Shadows is certainly one of 2014’s funniest movies, a consistently hilarious take on vampires that thankfully puts the focus on keeping the jokes coming.

Drunktown’s Finest

Screens October 23 at 8pm

Taking place in a small New Mexico town described as a place meant for people to leave, Drunktown’s Finest opens with someone asking why people continue to stay. The rest of the film tries to answer that question by focusing on three Native Americans; Nizhoni (Morningstar Angeline), an adopted child trying to find out about her biological parents before heading off to college; Sick Boy (Jeremiah Bitsui), trying to stay out of trouble before going into basic training; and Felixia (Carmen Moore, excellent), a transsexual trying to become a Navajo model. All three characters share a desire to leave, hoping to make a better life for themselves outside of town.

Writer/director Sydney Freeland creates an earnest, well-meaning drama about identity and people’s connection to their roots. Freeland’s writing may lack subtlety, with a lot of on-the-nose dialogue expressing her film’s themes, but it has a great sense of character, providing well-rounded portraits of its three protagonists and their individual struggles. By the end of the film, where a ceremony brings the cast together, Freeland provides a clear answer to the question opening her film. The town may be lacking in opportunities, but its strong sense of family and community is the sort of thing that’s hard to walk away from.

Trick or Treaty?

Screens October 25 at 5pm

Alanis Obomsawin’s documentary premiered earlier this year at the Toronto International Film Festival, but those who missed out catching it the first time should try to see it during this festival. Obomsawin’s documentary may feel lacking in its presentation, a rigidly conventional form that feels a bit bland, but its content is absolutely vital. Treaty No. 9, aka the James Bay Treaty, was signed in 1905 by the Government of Canada and representatives of First Nations across Northern Ontario. First Nation leaders believed they were signing a treaty that promised their customs and ways of life wouldn’t be impacted by the government, so long as they let the Canadian government own the land. In reality, the treaty was an unconditional surrendering of the land to Canada. The government could do whatever they wanted.

Obomsawin shows evidence that government officials tricked First Nations officials into signing the treaty, essentially promising them whatever they wanted just so they could get a signature (due to the language barrier at the time, the terms of the agreement could only be explained orally). The film structures itself by looking into the past, present and future over the central issues surrounding the treaty. The first third explains the history of the treaty, while the second third focuses on the Idle No More movement, a series of protests by Aboriginals over Bill C-45, a piece of legislature making major changes to various environmental bills without consulting with First Nations groups. The final third looks to the next generation by showcasing a 1,000 mile trek taken by Cree youth to Ottawa in support of Idle No More. Obomsawin makes sure the anger from her film’s subjects always registers, but looks at the protests as a hopeful sign that change is on the horizon.

SOL

Screens October 24 at 5:30pm

In Igloolik, Nunavut, tragedy strikes a family when Solomon Uyrasuk, their young, talented son, dies while in RCMP custody. Officials rule the death as a suicide, but the family believes there might have been foul play. Directors Susan Avingaq and Marie Hélène-Cousineau don’t turn their documentary into a murder investigation. Instead, they use Solomon’s story to shine a light on a health crisis occurring in Northern Canada: an alarmingly high suicide rate, especially with youth. Every year the RCMP receives over 1,000 calls for suicide or suicide attempts in Nunavut, a province with a population of 35,000. The suicide rate in Nunavut is 13 times higher than the national average. With figures like these, alarms should start ringing for the government. Instead the issue is largely ignored, with one interview subject observing that suicides in Nunavut are treated as “just another thing to manage.”

And while Avingaq and Hélène-Cousineau expand their scope to cover an issue impacting all of Nunavut, they never forget what inspired their film. Footage and interviews of Solomon show he was a likable, talented performer, getting his start as a child actor in a TV series. In his adult years he joined a circus through a youth program dedicated to fighting against suicide, travelling to different countries as a performer. Avingaq and Hélène-Cousineau argue Solomon’s loss, among many others, could have been prevented, his actions a result of external factors more than internal ones. It’s hard to disagree with them, especially when their presentation is so affective and gorgeous (the widescreen compositions of Igloolik add a layer of sombre beauty to the proceedings). SOL should hopefully go on to gain greater exposure, as its subject matter begs for a wider audience.

This May Be the Last Time

Screens October 24 at 11am

Similar to SOL, director Sterlin Harjo uses a tragic incident to explore a larger issue. In 1962, Harjo’s grandfather mysteriously disappeared. When the local Seminole community searched for his body, they sang old hymns to help them find Harjo’s granddad. Harjo quietly looks into his own ancestry, as well as the origin of the hymnal music practiced by members of his tribe.

The results of his inquiry are fascinating, with the music having a background connecting it to Scottish missionaires, Appalachian music and Gospel hymns. The film’s title comes from a hymn that was a favourite of Harjo’s grandmother. Harjo finds out the song had its origins as a slave song in the 1800s, before going through gospel and blues to end up as a song by The Staple Singers in the 1950s. The Rolling Stones heard the song, and made their own version called “The Last Time.” Harjo gracefully tracks other hymns back to their origins, and in doing so highlights an aspect of music history that’s largely gone unnoticed.

Harjo ends things on a bittersweet note, closing with a hymn while commenting on how the tradition of sharing and learning music is slowly dwindling. This May Be the Last Time gives the now dying form of music its proper due.