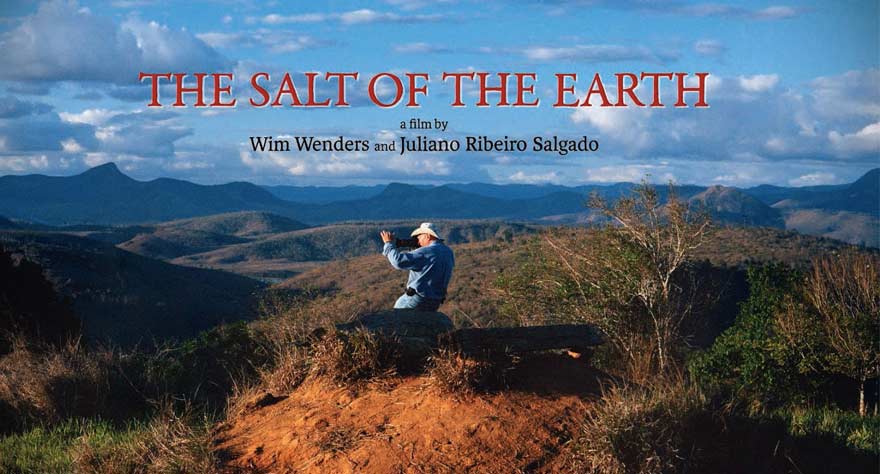

‘The Salt of the Earth’ Co-directors Wim Wenders & Juliano Salgado Talk Protecting Photography in Film

Legendary documentarian Wim Wenders (Buena Vista Social Club, Pina) received his third Oscar nomination for his latest film The Salt of the Earth with co-director Juliano Salgado; however, their collaboration nearly ended with the two filmmakers making separate movies. “It was at the point we had to either say, ‘Okay, goodbye Juliano you make your own film’,” began Wenders, “…we knew we both had material to make a respectable film. But deep in our heart we both knew the film we could possibly make together would definitely be better than the one that each of us was able to do.” The Salt of the Earth follows renowned photojournalist, and Juliano’s father, Sebastião Salgado. Sebastião’s work as brought him around the globe and to some of the world’s most overlooked, dangerous, or remote areas; however, the several-year-long story behind the documentary’s production proved to be its own dramatic experience.

Sitting down with Way Too Indie and other journalists, Wim Wenders & Juliano Salgado discussed dedicating time to properly understand your subject, viewing your work objectively and the unseasonable temperatures in the Kodak Theater for the Oscars.

How different is the process of thinking about photography versus film?

Wim Wenders: I don’t think I would have dared getting involved with a film about a photographer if I hadn’t known already that this man — who I had already encountered for a couple of month and became friends with — if I hadn’t known he was a great storyteller. If I hadn’t known that, I don’t think I would have dared to enter the territory of a movie because photos in a film need protection.

Without protection they become a slideshow and my own photographer friends have always refused to have them on a screen because I think they lose something. That’s why I liked them as prints or in a book, but on a screen it’s difficult. I feel as if they’re strangely naked and I only got involved in this adventure with Juliano realizing Sebastião himself was the answer, and the wealth of his stories and the knowledge of his economic, political, sociological, psychological knowledge of all the places he went to: that was going to make it possible to make a film.

Juliano Salgado: That’s what we shared, actually, when we started. It was the idea that we were not going to make a film of the photographer, but what one of the great witnesses of the last 40 years. Someone who had lived so much, had so much to pass on. You could see the photos in the exhibitions, in the press a lot, in books, but no one knew about all those stories and all those things Sebastião saw. It was really important that we could share this with a much broader audience than just the friends and the family. There was something important to pass on. That’s what we believed. That’s how we started.

So you would say the story is what’s protecting the photography?

Wim: Yeah, it’s the knowledge that what lead him to take these photographs and to share this process of getting involved with all these people and their situations. You see Sebastião has this uncanny ability to become part of the humanity he’s witnessing. And I was of course very curious how is that possible because I saw something in his photographs that I didn’t see in any other photographs. I saw an empathy and I saw an “immersement” and I wanted to understand that. I finally found out it’s time.

This man spends more time with these people and he spends more time to prepare himself. And then when he goes there he doesn’t take the next plane out because it’s uncomfortable, he stays and lives with these people under their conditions. He eats, he shares the same food. He stays, and he comes back. He sometimes comes back countless times because he feels he’s made friends and he can’t abandon them. He has a different implication and for me that was a huge discovery and it was also a slow realization that I only had a right to make a film about this man if I did the same. If I applied his own rules and that meant I had to spend three and a half years with him and his son in order to have a right to make this movie.

How significant was it for Sebastião to have a partner, like your mother Lélia, to allow him to do his work?

Juliano: It’s very significant. It’s very important that they’ve been together. Not only have they made important decisions of moving from the little town of Victoria to São Paulo then to France to move away from the economist career. Take the risk to become a photographer, to lose a prosperous life, actually. But more so afterwards, sharing the load of the hardship of the world. Lélia was the person that would help Sebastião listen to the stories but also they would decide together where he would go to, how they would formulate, and how they would conceptualize the work. So they pretty much have a [shared] story. All Sebastião Salgado it’s really Lélia and Sebastião.

There’s one little story that says a lot about the acceptance and the resilience. Lélia had to accept a lot to have her husband leave and she would stay at home with two kids, one of them with Down’s syndrome. It wasn’t easy, but she accepted it also because she knew it was really vital for Sebastião to make those travels. There was a reason for him to do that. It was bringing awareness and those photos had a role to play. But the way that she accepted it’s really peculiar actually.

It happened in 1974 or ’75. In Angola, there was a war, the Portuguese were coming out of Angola and the South African army was entering and taking all of the power there. They were fighting against rebel movements, Marxist movements, which were in the capital in Luanda still protected by the presence of the Portuguese. But they would leave and the day that the South African army would enter and would kill everyone that was not in Angola.

At this point, the diplomatic people are leaving the country, the journalists are leaving the country, everyone is leaving. And that day my mom is in Paris driving my dad to the airport, because he’s going there. He’s the only one going there. And she’s so worried, she leaves him, he enters the gateway, disappears into the airport. Ends up flying, and my mom drives back home because she’s so sad because it’s “obvious” he will die. She’s driving back home and she’s crying, and she can’t drive anymore so she stops by the side of the highway.

She’s there crying and she remembers Sebastião when he’s entering the airplane, and he’s the happiest guy. He’s like a child, he’s going to this place, it’s fantastic, there’s so much happening. Then she realized that she shouldn’t worry because he’s not. She will just worry something happens, and of course nothing ever happened. I think from the way Sebastião traveled, there’s a lot of protection because he actually travels [because] he mingles with the people that he’s traveling with.

He adapts and he gets accepted in communities. That’s the way you can travel to those dangerous places, being part of the communities because they know the rules. They know what’s dangerous, where you can go and how far you can go. So that’s the way he’s always been protected and Lélia’s always accepted that. But she’s been a great part in choosing of photos.

Wim: It was not so easy to convince her to be a part of the film. She felt her part has always been behind-the-scenes. She was the driving force — even the research done that they did together. She felt that she should remain in the back and it was not so easy. It was a lot of Juliano’s shoulders to convince his mom to also be in the film. In the end she’s just in there enough so that people understand the importance of her presence, the incredible relation these two people had together and this incredible load that she was carrying as the woman of that man who is never there.

Juliano: And amazingly that’s one of the first things we agreed on with Wim was actually show Lélia and to show how important she was from the beginning. So there was pretty much a question that was there from the beginning to the end of this process.

One of the interesting things about seeing the film is how it changes your view of the photos, it sort of better contextualizes the photos. You have a better appreciation for the fact that they’re a still image as opposed to moving image. It would have been very different if it were just a documentary film of the things he’s seen and done.

Juliano: For me, still pictures actually have movement. When you watch a still picture, your eyes are drawn to the focal point and then you start watching the details that are around it. When a photo is rich and complex, and most of Sebastião’s photos are, you suddenly start understanding that focal point better. There is movement in the way that you understand the photo. In this film, Sebastião’s always giving so much contextual information that you end up understanding the photos in such a different way from the moment you started watching them to the moment you switched to the next photo.

Wim: It was kind of scary for us to see — we took the pictures always for granted. Some of them we filmed ourselves [pulling] from the box so we had [the footage] for editing and we thought we knew [the photos] so well. We went to count those pictures and sometimes even in the editing process, working with these simple files of pictures we broke down. We had to stop editing because sometimes it was just too much. So at the end we thought we knew these pictures and we were to live with these pictures and the choice that was in the film was made.

Only then we asked Sebastião to interfere and make sure to give us high resolution files of all the pictures that were in the cut. We cut them in and in the editing table they looked a little better but they didn’t make a big difference. And then the two of us saw for the first time the film on a big screen. I remembered very vividly because it was a shock. I, for the first time, saw the pictures that we had now witnessed for a year in a half in the editing room on a screen and it blew me away how much more I saw.

And I sometimes felt we left them too short. In the editing room we always fight to keep space around the pictures and not cut them so much. Then on the big screen I thought, I could watch these pictures on the big screen for hours and hours more because there’s so much on them. That was a huge shock, to see them for the first time on a big screen.

What did you learn from watching Sebastião work?

Wim: I learned one thing more than anything else: he invested time. When he was photographing he forgot about time, he forgot about his own life, and he gave all the time that was necessary for a project and sometimes it took years. I realized in my own world and also as a documentary filmmaker we don’t have that. I am part of those who come in and out. I realized for this film I had to dedicate three years to this man in order to be on his level. In order to have a right to make this movie.

There are other things he does differently that other photographers. It’s not just the timing, it’s also the uncanny ability to connect via his photographs.

Juliano: Yeah, I really think Sebastião’s great talent it’s… you know, of course the black & white is beautiful, so profound. The composition is always amazing but it’s that actually he manages to connect with people and intuitively he knows where to put the camera so you actually feel that emotion. That thing that’s happening there between him and the person, or even the landscapes sometimes, you feel that. That breaks the distance. It’s amazing when you see his pictures that’s my feeling. You really don’t feel a distance with people who have such different lives than we have. His great talent is that he can put those emotions in the picture.

Juliano, you’ve mentioned that in collaborating with Wim it helped you get distance from the subject. What did the distance help you gain?

Juliano: It was absolutely necessary. When we started, I’m going to make it really brief, at first I thought I was never going to make a film of my father because our relationship was so difficult. Then he approached me, kind of forced my hand so I go with him to this trip in Amazonia with the Zoe tribe. I’m there with him and the Zoe are so nice, they contaminate us and we end up being nice to each other as well.

I film with Sebastião. You know the camera says a lot about the person who is filming actually. And I think sometimes it more about who is filming than who is being filmed. When Sebastião, back in Paris, saw those pictures edited, [he] was very, very touched by them. We started some kind of a healing process of our relationship, but also it gave me the certainty that maybe it was the right time to make a film about Sebastião. Genesis was supposed to be his last, great project. To think about what it could be I realized that the important thing from Sebastião was sharing those stories and we realized that Wim had the same intuition.

But for me, it was completely impossible to make those interviews because of how close we were, and because the nature of our relationship was so complex. It had to be done by someone else. And when Wim accepted to be part of this adventure it was amazing because suddenly it was not only the guarantee that there was someone there who had an outside perspective, who knew about images, it was also the guarantee that there was so much more to the film. From a very talented guy.

How closely do you feel the man that you know as your father?

Juliano: I think very close actually. That’s the weird thing. When you see Sebastião in everyday life you don’t think he’s got this zen attitude about the world and he understood how to balance himself, but there is something about that in the artist trajectory. Somehow it took over and I think I discovered Sebastião, to be honest with you, when I saw Wim’s interview of Sebastião.

We knew the stories, we had to choose those things very carefully. When I saw the result of that seen by Wim’s eyes. He needs to tell you how he did it, it’s amazing actually. When I saw that I understood so much about Sebastião it helped me do that further step. It actually completed our healing process. It was suddenly, right after I saw that, we met again in Paris, we were editing in Berlin, and that’s it, we were friends. It’s really weird it’s not like a long process. It’s something that happened suddenly.

Wim: I became the family therapist [laughs].

How do you carefully place your narrations over these images?

Wim: We for the longest time thought, as we were editing the film, that there’s only one voice in the film and that’s Sebastião. He’s telling you all these stories, so the golden rule is the two of us will completely refrain from interfering. It took us the longest time to realize that was the wrong approach and that we also needed to appear as narrators. To sort of find the trick to be alternating narrators, and sort of throw the ball to each other and become two voices without interfering with the fact that Sebastião was the overall voice. It took us the longest time to accept it. I actually brought his man in with a dirty trick.

Juliano: Very dirty.

Wim: When I realized the arc of the film was not holding if the two of us wouldn’t step out of the closet and become also narrators. I had all these family photos that we had gathered. I started a couple pictures in. It started with a little picture of a baby boy lying there as a bundle and I cut it in and the next time [Juliano] saw the cut he was in it.

Juliano: And I was awful, actually. I was so camera shy. I saw it thinking, “I’m going to cut it out. I’m going to cut it out. I’m going to cut it out.” But at the end of it, it was so sweet and it belong to the film.

Wim: It was a great way to also introduce you as a voice and as you grew up and had a voice.

Juliano: Absolutely.

Wim: It was a huge learning process for the two of us how two men can make one film.

So did you manage to succeed as a therapist?

Juliano: There was a lot accomplished you know, but actually it took us a year before we found out how to work together in this film, editing-wise. At the end we did but after a year of trying, editing. Each one on our own material, or the whole thing but by ourselves. I would try for two months, Wim would see the result, hate it and take the material to edit for three months. Then the result wasn’t that great either. Actually we got to the point where we finally decided we’re going to try to sit together in the editing station. It’s very difficult, it’s like writing an article. You have the information you have to put in the paper, and then you have a gut feeling. You have a way of writing and that’s your own sensitivity. There’s only one way.

Wim: And sometimes you have to do this thing together. It’s impossible, and we felt with this story it was impossible. Until finally it was at the point we had to either say, “Okay, goodbye Juliano you make your own film, it’s going to be very nice and I’m going to make my own film, it’s going to be nice.” And we knew we both had material to make a respectable film. But deep in our heart we both knew the film we could possibly make together would definitely be better than the one that each of us was able to do. So evenetually we said, “Okay, Juliano, I’m going to cut your stuff and you’re going to cut my stuff, and we’ll see what it looks like.” And that was painful, and that was not the solution. The solution was the next step, we forget who’s is who’s. This is not your’s, this is not mine. We sit together in front of the editing table and we cut it together. That took us so long and we fought to the bone.

Juliano: This guy is stubborn [laughs].

Wim: And then, when we finally gave up each and every ego tendency a director can have on this planet, we had it our common film. Then the Sebastião showed up that we both saw.

Oh boy, but was it painful. I’m never going to do this again [laughs].

What did Sebastião think of the film?

Juliano: Sebastião saw it for the first time a few months ago in Rio. When we were about to finish the edit we sent them a little file, you know? A low-res file so they could see it, make sure there was nothing there that they couldn’t go with. And hopefully there wasn’t.

Wim: And they didn’t see it at all during the entire process. They saw it when it was finished.

Juliano: And when they saw it for the first time in Rio, we were in the Rio Film Festival, it was so emotional. They were holding it together until the moment Sebastião’s dad comes in for the first time and starts speaking about what he thought Sebastião should have done, “a lawyer, an economist.” Then suddenly Sebastião breaks down, starts crying, it was so emotional and Lélia, too. It was really beautiful, actually, it was a great moment.

Wim: He called me afterwards from Rio. He called me afterwards and it was unforgettable because until then I really didn’t know how they were thinking about it. We made this film for three and a half years and I really didn’t have any feedback, and I was always a little worried, didn’t know if we had done something right. Then he called me from Rio and he was still very emotional and that’s when I realized, “Ok, they can both live with it.”

How were the Oscars?

Wim: Cold. I got my cold in that Kodak Hall. You know, you don’t see that on television. It’s freezing cold in there. Because I asked actually the manager of the place, I went out and said, “Why does it have to be so cold? We’re all freezing our butts off.” My wife took off one of the camera’s the black wrap and wrapped her shoulders in it because she said, “I can’t stay in here because it’s so cold.” They told me, “We have to keep it at this temperature so the make-ups won’t melt.”

The Salt of the Earth opens March 27 in New York & Los Angeles