Stephen Beresford & Jonathan Blake: Gay People Can Take A Punch–We’re Tough

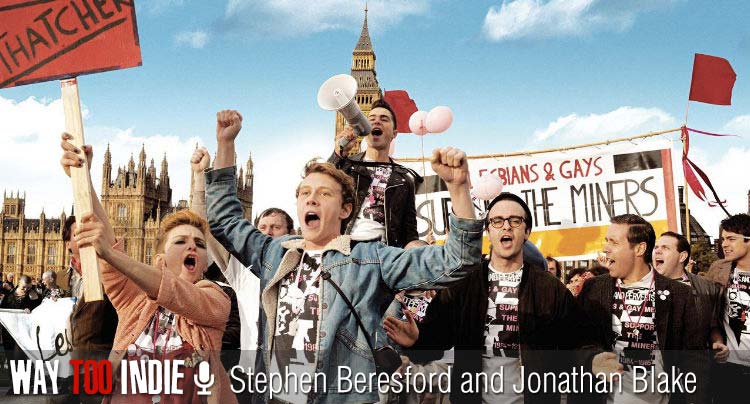

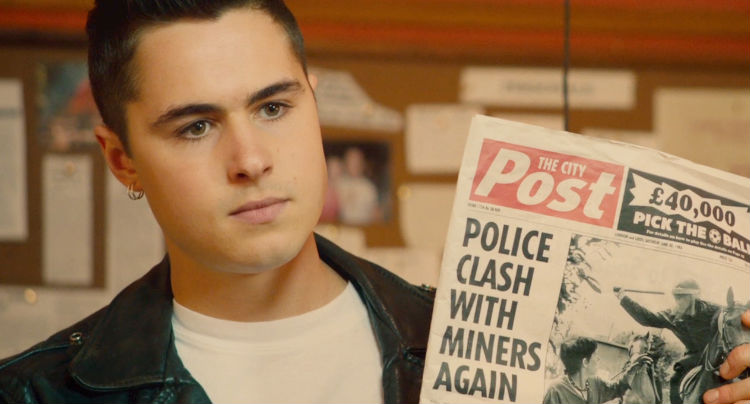

Matthew Warchus’ uplifting crowd-pleaser Pride follows the true events of the 1984-85 UK miner’s strike, which saw a group of young gay activists called Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) come to the aid of the working-class union. The sprawling ensemble piece was penned years ago by Stephen Beresford, who designed the story to reach a wide audience and spread a positive message of hope and empathy.

The Wire‘s Dominic West plays a disco-dancing party animal in the film based on real-life LGSM member Jonathan Blake, who was one of the first people in the world to be diagnosed with HIV. We spoke with Blake and Beresford in San Francisco about their memories of the strike, growing up under Margaret Thatcher’s regime, the first time they met, writing a true ensemble piece, Chekov, lemon cakes, and more.

Stephen, what was your memory of the 1984 miner’s strike?

Stephen: I was a kid during the first miner’s strike, so I only really saw it on TV. Where I grew up, which was by the sea in a very prosperous part of the UK, Margaret Thatcher was a god. The miner’s strike was something people didn’t take any notice of at all, except my parents were pro-miners. My mom’s friend made a cake for for the church and iced it with “Victory to the Miners”. There was a lot of fuss from the vicar and the ladies. [laughs] But on the whole, I was pretty oblivious to the strike. I remember finding it quite frightening. When you grew up in the 1980s in the UK, and even here, you felt like there was a lot of change happening. We lived under the constant threat of nuclear war, so the strike felt like a part of those social changes, which were often accompanied by violence and trauma.

There was a second strike in the ’90s, and correct me if I’m wrong, but you didn’t support the miners.

Stephen: That’s fair enough. I didn’t, really. I’m of the generation they call “Thatcher’s Children”. She was elected in 1979 and was very influential. My whole development happened under Margaret Thatcher and her government. I grew up under that system completely, and it was very pervasive. Where we lived, we didn’t take notice of our environments. We just thought, “This is the world.” I had never questioned those things. Stuff earlier generations thought about, I never did. The idea that there was a common bond between people and that our struggles were all the same was a completely alien idea to me. As Margaret Thatcher said in one of her famous speeches, “There is no such thing as society.” That’s how I grew up. The idea that justice and equality didn’t happen naturally in the world and that you had to make them–that was completely alien.

I was gay and young, and I was very fearful. My attitude was, nobody’s going to look after gay rights except gay people. That’s my tribe. It’s not that I was anti-women’s rights or anything like that, I just only focused on gay rights. The minute my friend told me the story about [LGSM and the strike], my whole world view [was changed]. Miners marched at the front of gay pride. All of the possibilities opened up for me. It was a very profound moment. What I’d like is for young people to watch the film and have the moment I had.

How does it feel, Jonathan, to have work you did 30 years ago inspire young people in 2014?

Jonathan: It’s extraordinary. What’s so strange is, we went out and we did it, and we didn’t really think about what the consequences were. And perhaps even more so for me, because I was going to be dead next week, you know? You’re living with HIV and, you know…I was diagnosed in October 1982, right at the start of the epidemic. It was a death sentence. Everything week that passed was like an added bonus. The great thing about LGSM was that it kept me busy. I was always one step ahead of the virus because I was always doing something, so there wasn’t time to get ill! It really wasn’t until Stephen turned up and said he wanted to write a screenplay about LGSM. He walks away and I thought, yeah, well…

Stephen: “That’s never going to happen…” [laughs]

Jonathan: But suddenly, I get another telephone call. “This is Stephen. I have written the screenplay and it’s going to be made into a film.” The doorbell rang and there was this tall gentleman standing there and he says, “You don’t remember me, do you?” [laughs] But anyway, he came in and said he’d written a character called Jonathan. It didn’t ring any sort of alarms. It was fine. Then, I got a call saying the director and the actor who is going to play you want to meet you. I asked when, and he said tomorrow. I thought, well that’s just enough time to make a cake! [laughs]

Stephen: A very good cake. Lemon drizzle!

Jonathan: You have to have cake to entertain guests. I went to the door and Matthew was standing there, and then I saw Dominic West. I was gobsmacked. They asked really open questions, about events, how we got into politics–the whole gamut. It was so easy.

Stephen: It’s funny how many people who, when I said I was going to write this film, said, “Yeah…okay. I look forward to seeing that…”

There’s a lot of power to this film. People say all the time that films are powerful, but there’s a real energy of positivity to yours.

Jonathan: The first time I saw it…[pauses, fighting off tears]…I found it really difficult. There were all these people who are no longer with us, who had been ravaged by the AIDS epidemic. They were all sitting on my shoulder. I couldn’t really take it in. Afterwards, Dai Donovan got up and made this amazing, passionate thank you speech. Here’s something we’ll be able to show future generations. There’s something in this film–the way it’s written, the way it’s directed, the performances–that just has that feel and flavor and smell and taste of the times. It’s extraordinary. I don’t know how it’s happened. It’s like magic. There are times when you sit in the theater when you get overwhelmed by the taste and the touch. This film has that.

Stephen: Matthew describes the story as a romance not between two people, but between two communities. In a way, it follows that formula. But because it’s about communities, it’s very crowded so that all sorts of points can be made very, very quickly. What’s important about the story and Matthew and the actors is that I’ve written a screenplay that doesn’t have any room for anything other than hitting it absolutely on the mark. Everything is totally specific. Almost every actor in the film is playing a part smaller than they would ever play. Everybody. Russell Tovey is in for less than 40 seconds. Bill [Nighy], Dominic, Andrew [Scott]–they would all play leads in other movies. You get this incredible precision in their work.

In Chekov’s plays, there are always three points in the story for each character where something is different. In Three Sisters, Anfisa the maid goes from one place to another, until the end where she has a room and a bed. It’s absolutely essential. Every single person has at least three places where the circumstances are different, and they express it. Our actors hit it completely on the money. It’s brilliant.

Like you said, this is a true ensemble piece with no central hero. It’s progressive, I think.

Stephen: And harder to sell, unfortunately. [laughs] Why I like writing like that is that you have to have complete faith in the actors. It’s simple dialogue, but it carries a lot. You have to believe that they will bring it. Everyone did a great job at every point, even people who played tiny parts. They got the tone. I find it very humbling to watch it.

What’s great about the film is that the gay characters aren’t portrayed as victims and aren’t sexualized.

Stephen: That was hugely important to me. Gay people can take a punch–almost all of us have had one or two! [laughs] We’re tough. The film shows that, and I’m very proud of that because that’s really important to me.