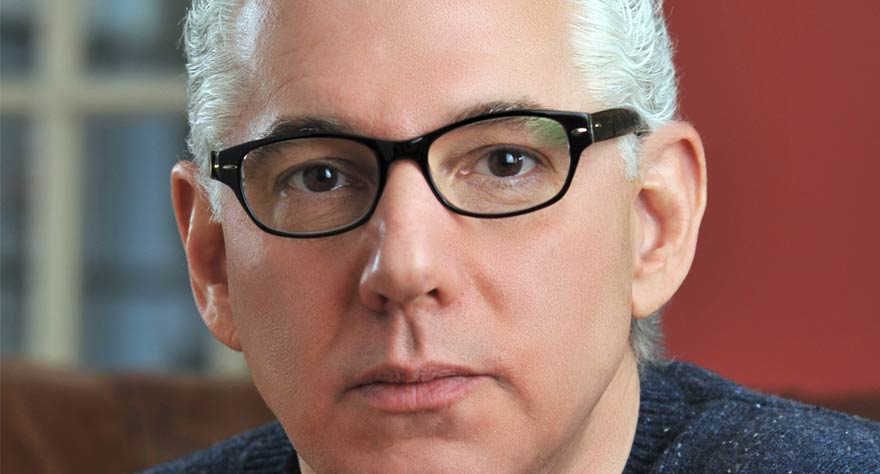

‘Kids For Cash’ Director Robert May Talks Moral Judgments In Documentaries

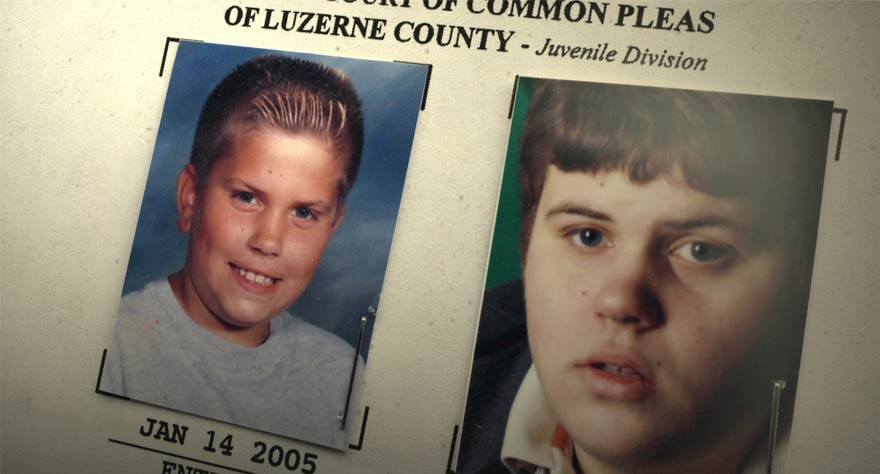

When the news of Luzerne County’s Kids-for-Cash scandal first broke in 2007, revelations about judicial kickbacks for sentencing minors to for-profit juvenile facilities sent shock waves through the news media. That shock was felt more greatly among the residents of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania than anywhere else, as President Judge Mark Ciavarella and Senior Judge Michael Conahan were highly trusted members of the community prior to their involvement in Kids-For-Cash. Wading through the haze of swarming media, film producer and Luzerne County native Robert May decided to dig deeper into this scandal with his directorial début Kids for Cash. In looking past newspaper headlines, he found significantly more intricacies and emotional complexities than the surface of this story would provide.

Speaking with the first-time director, but seasoned producer, about his new film, set to hit DVD tomorrow, December 2nd, I spoke with May about handling dual roles, discussing deeply personal matters with strangers, and navigating 600 hours of compiled footage before editing.

How did you first come across this scandal and how quickly did those thoughts turn to, “This should be a documentary”?

Robert May: My producing partner and I were developing another story, a fictional story, at the time when the scandal broke which was in January 2009. I live in Pennsylvania even though my offices are in New York. We were actually working in Pennsylvania on this other project, so when the scandal broke… we were together for maybe about a week at this story retreat and every day the headlines were getting worse and worse, and then it was on television & radio stations, and then it was international news and I was like, “What is going on?” Because I knew these judges, I actually live in the county in which this all happened, but quietly before all this.

I kept reading about it and it just seemed so unbelievable to me, and I knew that these judges were very celebrated in the community and they had been around for a long time. [It felt] like, “How could this happen?” It just sounds so draconian, you know? One day they wake up and they’re selling children? It didn’t make a lot of sense and so I was very curious about it because the media at the time was really, very one-sided. It was just all that they were selling these kids and it was the big scheme, and that made me really curious as to, what was actually going on here? Was there more behind it?

When you came across this material that was so close to home did that have any influence on your decision to step into the director’s chair?

As a matter of fact I didn’t originally intend to direct it. When you’re producing documentary, it’s a fine line between producing, directing and editing, because if you’re creatively involved you’re creating the story as you go ‘cause you don’t know what the outcome is going to be typically. Whereas in a narrative feature you follow the script and so forth.

So in this case, my intention was to go to some of the directors we’ve already before but when I did, I really got a lot of encouragement to consider directing it myself because I was really well-prepared. Like Steve James for example who I’ve worked with on a number of occasions, on Stevie one of his films a number of years ago and then The War Tapes, that I produced that I brought Steve on to edit, and it was a first-time director we both worked with there. Creatively, Steve and I and my producing partner we were really creatively involved with that way that film turned out so I just got a lot of encouragement. “You should go, you should do this yourself, you’re ready.” That’s when I decided to do it and I became very passionate about the subject as well.

Did that type of experience help you avoid some of the issues that typically affect first-time directors?

Maybe. I’ve dealt with a lot of first-time directors. Tom McCarthy, who was a first-time director who wrote and directed The Station Agent. I took a real chance on him and really believed in him. We’ve worked with other first-time directors as well, so I’ve seen Tom McCarthy who did an exemplary job as a first-time director but not all of our first-time directors experiences have been as great as say Tom McCarthy. So I’ve seen the good and then the challenging.

I think being a pretty tenacious producer, and I’m very anal in the way I do things… You know, always watching for things to help protect a first-time director, and yet have a producing hat on, it was harder than I thought because I had to produce and direct and the lines got blurred a lot of times. I’m still arguing with myself about certain things. But I had the discipline as a producer and I think that helped me avoid some of the pitfalls first-time directors get into.

Plus, I really did have a lot of support. Like folks like Steve James and Tom McCarthy, who gave me notes on the cuts. I’m pretty collaborative so it turned out to be a really great experience.

How long did you spend making this documentary?

We started in 2009 and picture was locked in late 2013, then it came out in theaters February ’14, so it was a long time. I mean, it was a couple of years of editing and also the last year I spent editing pretty much by myself. The first year we had a team of editors on it but we were closely getting the story in line. It was a complex story to tell. We shot 600 hours of footage to get to the 102 minutes. Our budgets were dwindling, so I took it on in the last year just to hone it and get it to where it is.

600 hours of footage sounds like a mountain of footage, at the end of that process how close of an idea do you have to what that final film is going to look like?

That’s an interesting question, I would say in the last maybe 10 months, 9 months or so, I started to see exactly what this story… In the very beginning we had no idea where this story was going because it was really a story about a small town scandal rocks a nation, then we discovered this whole, big issue but I didn’t want to make an issue-driven film. For goodness’ sake nobody would see it. So it would be like, “Now what?” Because we had this entertaining twist, we had access to these two judges, the villains, and I always wanted to tell a story from the villain’s and the victim’s perspectives, that was set right from the beginning.

But both of them gave us more than we bargained for, if you will, and so I think I ended up making the movie I wanted to make but it was a lot more complicated than I thought. Because it’s a story of villain and victim, but it’s also a story where the villain, while earmarked by Judge Ciavarella and Judge Conahan, the villain I think in the movie is even broader than we thought. I think the villain of the movie is society as a whole. And also local communities who don’t know what’s going on with their own children in the community in school and so forth. So the villain role was really expanded beyond the two judges, that’s when it became a little more complicated.

You mentioned that you actually got these two judges to sit down with you. A lot of times in documentaries about people who are the subject of scandal, we don’t get to hear directly from that person, so I’m curious what it was like getting in touch with Ciavarella and how you got him to agree to be in your film?

First of all, I really didn’t think it was gonna’ be possible. Again, I was working on this other project when the scandal broke and we kind of shifted for a day or two and said, “We should look into this project but we should only make it if we can get access to the judges,” and I really felt that was going to be pretty impossible. They’re going through a federal prosecution, why would they talk to us? They had nothing to gain. I didn’t know them either so I had to figure out how to get to them, so I was able to figure out how to get a meeting with Ciavarella, and then from there my pitch was, “Look, I’ve read everything there is to read about so far in this story and it seems like a very one-sided story… I’m interested in telling the story from both the villain and the victim’s point of view,” and I said to him, “You’re the villain.”

That’s really what interested him I think. He was vilified, regardless of his guilt or innocence, he was certainly vilified in the public and the media and so forth. And I was curious too because everybody loved the guy and they agreed with his zero tolerance policies right up until they found out money was involved. Then they were like, “Well wait, what are we doing to these kids?”

It was really that, that I was going to tell the story from both sides… He said he’d think about it, then a little bit of time went by and then he approached me and he said, “I’ll do it under the condition that I don’t tell my lawyer.” I’m like, “Well… you’re a lawyer and you’re a judge so as long as you sign our releases and stuff it’s fine with me.” And that’s what he did. Then the other judge was a similar thing. I approached him similarly.

What’s the importance to you in leaving moral judgments out of the film and allowing the audience to come to those conclusions on their own?

I think it’s a big deal. I don’t like documentary films that literally preach. You start the film, you end the film and you know a little bit more about what you knew going in and I just don’t think that’s the way life works. For me, to be able to get to the bottom of what happened, or try to understand what happened, it was really [about] going in there in a non-judgmental way. First of all they’re not going to talk with us if we’re going to have an attitude with them or judge them, but I was curious because a community literally loved these guys.

As I said earlier, they sent kids away on minor infractions and the community and schools, everybody loved it. Then everyone immediately distanced themselves from his practices once they found out money was involved. Well, why weren’t they questioning the practices before that? I think what we found in screenings all around the country, but for the money, the kinds of things that were happening in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania were happening around the country. You could never get to that point if all we did was just say, “Okay, this guy took money. That’s a bad thing.” And then at the end of the movie yeah, that’s a bad thing. But we would never understand how could he have done it all these years and no one said anything? There was a lot of complicity and complacency.

At the end of the day, I think that audiences are a little stunned. The film makes people feel uncomfortable for sure. It starts out just like the story was. This villainous guy, what explanation could there possible be? And then it goes into a very complicated story, because it goes into the grey of how we get into these kind of things as a community or as a society or just a person.

In the early stages, it feels like you’re telling a black-and-white story and then you see all the grayer aspects to it.

That’s right.

Did you have to discover those for yourself? How much of that work was on you as a journalist?

That’s exactly right, I didn’t know it either and I thought he was as evil as everybody thought in the beginning and then I realized it’s much more complicated than that. I think we discovered this story as the audience discovers this story. I think that’s the best way to put it. And that was important to tell it that way because you’re seeing how people react, they reacted in a very one-sided way to the judge, but they really didn’t understand the huge impact that caused this to happen in the first place, and caused schools to funnel kids in to him, or police departments to funnel kids into him. So it literally took a village to create him and what happened. I think this film throws out all those questions without actually being obvious about it.

There’s a very tense scene later on in the film that takes place outside of the courthouse with Ed’s mother confronting Judge Ciavarella, when that moment happened were you lucky to catch it or did you know something was going to happen?

We had no idea, as a matter of fact we hadn’t even met her prior to that day. We told her story in reverse. We had two cameras there and it caught the entire exchange. It just so happened that one of our [cameramen], our DP in that case, was standing right next to her. Nobody knew who she was, I didn’t know who she was, and that’s what happened. And we got it and that changed the course of the film, too. It was the worst-case example of what can happen with a kid [that goes into the juvenile system]. You have an altercation between a villain and a victim right there and then after that happened, that’s when we contacted her to try and find out the depth of her story.

In getting into aspects like her story, you’re asking a lot of people some very uncomfortable questions, recounting very uncomfortable details. As a documentary filmmaker, what’s it like to go to these normal people and ask them to reveal themselves?

I’ve had some experience with that, because some of the other films even though I didn’t direct them I was there for some of the interviews, did some interviews. But what was different here was we had some very long days, our crews were out of New York so we had to utilize them carefully. So we would set up interviews in the morning and in the afternoon. One in the morning, one in the afternoon. Sometimes we would be interviewing a judge in the morning and the kids in the afternoon or vice-versa. And I can tell you at the end of every day, all of us were completely and emotionally drained by those interviews because judge for example would completely trust us and we kind of had a really good rapport with him, very conversational. Neither judge knew, at least officially I don’t know if they knew privately, that we were filming the other, but they both acted very similarly.

When I would leave they would say, “Look, I feel so much better after talking to you, this is almost like therapy.” And the same thing would happen with the kids and families, too. They’re pouring their hearts out and none of them know we’re talking to the other. I knew that eventually we’re going to have to share this with the families as well, so that weighed on my mind. But I would say that the emotions of those two sides of the story on a daily basis was a lot. It was a big deal. I have two kids and a family and I would come home at night and I’d be drained from these interviews.