Joe Berlinger Talks ‘Whitey: The United States of America v. James J. Bulger’

Joe Berlinger has spent over 2 decades creating critically acclaimed documentaries, making him one of America’s leaders in documentary filmmaking. The Oscar-nominated director, responsible for films like Brother’s Keeper, Metallica: Some Kind of Monster and Crude, is most famous for his collaboration with Bruce Sinofsky on the Paradise Lost trilogy. Released between 1996 and 2011, the three films followed the witch hunt and unfair convictions of the “West Memphis 3,” with Part 3 culminating in their release from prison.

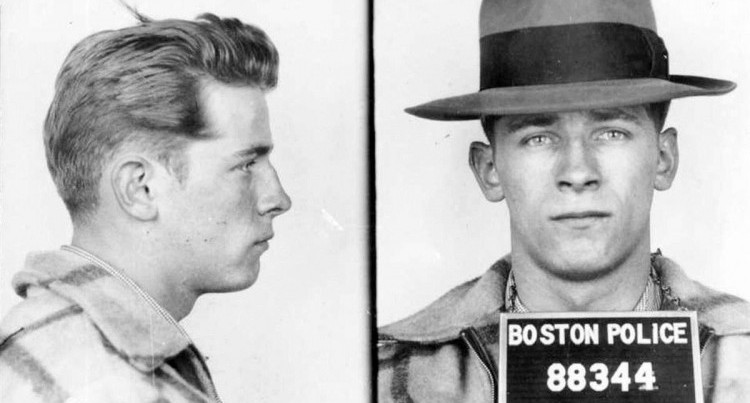

Berlinger returns to true crime for his latest film Whitey: The United States of America v. James J. Bulger. Berlinger focuses on James ‘Whitey’ Bulger, a crime lord in Boston responsible for a multitude of offenses including murder. Whitey escaped the FBI until his arrest in 2011. The documentary was filmed during Bulger’s trial last summer in Boston, and the film interviews family members of victims, defense attorneys, prosecutors, government officials, and plenty more to paint a picture of Whitey’s reign of terror over Boston.

But the film makes a shocking suggestion. The FBI claims that Whitey was an informant, but Berlinger lets Bulger’s defense team lay out their argument that Whitey never informed on anyone. In fact, he had different FBI agents in his pockets to make sure he wouldn’t be taken down by the authorities. It’s a dense, complex and messy tale, one that Berlinger effortlessly handles without losing viewers. Earlier this year at the Hot Docs Film Festival I sat down with Joe Berlinger to discuss Whitey. He talked about the different aesthetic challenges facing him on the film, his approach to documentary filmmaking, and Boston’s reaction to the film, among many other topics. Read on for the full interview, and be sure to check out Whitey: The United States of America v. James J. Bulger in theatres now.

For the Paradise Lost trilogy you and Bruce Sinofsky went into that case at the very beginning, watching everything unfold. Now, with Whitey, you’re coming into a case with decades of history behind it. What were the challenges facing you as you came in to start filming a story with such a long and notorious background?

It was a very challenging film to make in that respect. First of all, how do you educate the audience on this huge backstory? The trial was the only present tense element of the film, but because federal trials are not allowed to be photographed I had no access to the trial. I had to think, how do I make a film that’s not just all talking heads and archival footage? I used a leitmotif of people converging and driving, so I did a lot of introducing of cars to try to give the film a sense of motion. I used aerial shots to make the courthouse and the city of Boston a character. I tried to amp things up visually. Not that I reinvented the wheel with this, but as a cinema verité filmmaker I did recreations for the first time. All of those things were challenging, but the biggest challenge was where to find a balance. It was like Metallica: Some Kind of Monster or Paradise Lost 3. If you never heard of Metallica or the West Memphis 3, how do you make a film for those viewers? How do you make the film accessible to those who know nothing about the subject matter while making it rewarding for those who know a lot about it?

Those were the aesthetic challenges, but I think the fact that I was coming into the trial at the end of the story actually provided the film with its driving force. The point of my film was challenging the conventional wisdom. So much has been written about Bulger, and to me the trial and the making of the film was the opportunity to separate the man from the myth. It was the opportunity to start looking at what the truth behind the situation is. And the truth is very elusive. One of the themes is that we don’t know what the truth is. One of the big questions driving the film is whether or not he was an informant. All of the media to date, all the books that have been written, the movies about to be made with Johnny Depp and Matt Damon playing Whitey in different films, they all take as gospel that Bulger was an informant. That’s not necessarily the case. The film establishes there are some deeply troubling questions brewing about the idea that he was an informant. One of the aesthetic challenges was to use the first third of the film to present the conventional wisdom and then start picking it apart. Aesthetically and thematically it was a big opportunity to come in at the end of a 30 year history and say “The things you think you know about this guy are not necessarily the case.”

I was impressed by how smooth the presentation is because the material is quite dense.

It was the densest film I’ve done to date.

What challenges do you have in presenting so much information to the audience without getting them lost in the details?

That’s exactly it in a nutshell, finding that balance. The use of aerials was there to give the audience some moments to breathe. To me, music is always important to me in a film. I felt like the score drives the action forward and helps the audience absorb the information. I don’t think I’ve ever used music this aggressively in the film. Some people have complained about it. They ask why there’s wall to wall music in the film. For me it’s to help tell a story and help provide a kind of dramatic thrust forward for a film that could have been bogged down in pure interviews. At the end of the day this is a largely talking heads film, but you don’t necessarily feel that. It’s just certain aesthetic choices.

It’s interesting because when you establish the forward momentum I think it makes people more open to taking in the information. I had to keep my attention on it because I felt that if I turned away for several seconds I’d miss a major development.

I’ve jokingly said “Please don’t text during this movie.” You take two seconds away and you’re gonna be lost for the rest of the film.

You had a lot of limitations in this film. For instance, you said in an interview that you only had the prosecutors for one interview. How do you handle getting across your goals or vision for the film with these limitations? How do you adapt yourself to handle these roadblocks?

I’m pretty relentless in trying to get as many people to co-operate as possible. I won’t rest until I can get their perspective in the film, and if I can’t I have to figure out another way to get the information in there. I also think it’s important not to have a preconceived notion of what your film is prior to its completion. Films are a process of discovery. When [Bruce Sinofsky and I] first went down to do Paradise Lost, we thought we were making a film about guilty teenagers. That’s what all the press was about [at the time]. We thought we were making a film about disaffected youth who could have done something so terrible as to sacrifice three 8 year olds to the devil. Had we locked in to that perspective and tried to just focus on getting that, we would have missed the real story. And after about 3 months of being down there, things weren’t connecting for us. We came to the conclusion that these guys were innocent.

Going into Whitey I didn’t think I would be sympathetic towards Bulger, not that I’m sympathetic to him as a human being. He’s a cruel killer that deserves to be behind bars. I think some of his claims deserve to be looked into, but were swept under the rug at the trial. The local media treated it as a sideshow when it was essential to the case. Of course you come into a situation wanting to tell a story, but what’s helpful is keeping an open mind. I guess the point I’m trying to make is that I don’t try to lock into a preconceived notion of what the film I’m trying to make is because sometimes you miss the story.

Have you considered revisiting Whitey Bulger’s story? There’s obviously a wealth of material here to work with.

I don’t know. Look, I thought Paradise Lost was it and then I ended up making three films over 20 years. The cut for Sundance was 130 minutes, and people felt the density and the length combined made it too long, so we cut it back to its current 107 minute runtime. I just don’t know.

How has the reaction been from the city of Boston?

There were some people in the audience who found the film really powerful, but what’s curious to me was the reaction of a handful of journalists who have made a cottage industry in writing about Whitey being an informant. I think they were being intellectually dishonest in their reaction to my film. They were highly critical that I would have the nerve to even mention the fact that Whitey wasn’t an informant. It was very ironic that they were calling me intellectually dishonest for presenting it when I feel they’re being intellectually dishonest for criticizing it. First off, the film is called Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger, so if one of the major defense arguments is that he’s not an informant how can I leave it out of the story? Secondly, those writers who said it was irresponsible for me to even bring that argument up should have disclosed that they’ve made a lot of money and made their reputation on breaking the story that he’s an informant. I think there’s a little pot calling the kettle black here.

Truth is a major element in your film. It’s very unlikely that you’re going to find the complete truth about what happened with Whitey. You’re not going to get, say, direct results from your filmmaking. What are the results you’re trying to obtain here? The film deliberately raises more questions than it answers.

I’ve had the experience in my career where, with the Paradise Lost films, Bruce [Sinofsky] and I got really tangible results. That’s a rarity. You make films for a lot of different reasons: you want to move people, you want to tell a good story, you want an outcome. Paradise Lost is one end of the spectrum where you have tangible results and an impact in people’s lives. But somewhere down the line you also want to start a conversation or debate. I don’t think I’ll ever know the truth about the Bulger case. The government should not be in the business of deciding who should live or who should die. My goal in focusing on the criminal justice system is that we need to believe in our institutions of government. We need to shine a light on injustice wherever it is so it doesn’t happen again. My desire for the truth to come out in this case is to provoke a dialogue. I don’t think there are going to be tangible results like in Paradise Lost. I certainly hope people will see this and understand that, if the justice system is run by human beings, it’s extremely fallible. We need to have clarity and truthfulness in the situation because it’ll happen again.