Jehane Noujaim and Karim Amer Rally at ‘The Square’

Egyptian-American filmmaker Jehane Noujaim’s rousing documentary The Square was born of a revolution.

In January 2011, Noujaim traveled to Cairo when she heard rumblings of an uprising forming at Tahrir Square in opposition of longtime President Hosni Mubarak and his military’s abusive oppression. She arrived at the titular square engulfed by an endless sea of protesters and, with no previous plans to make a film, broke out her camera and started shooting.

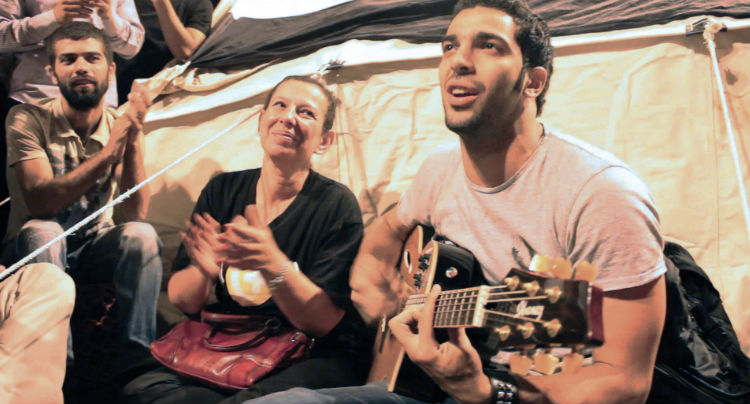

There, in the square, she met Karim Amer (who would become her producer), the rest of her crew, and three men who would become her cast of characters; Ahmed Hassan, an limitlessly spirited and vocal revolutionary; Magdy Ashour, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood; and British-Egyptian actor/activist Khalid Abdalla, who had also flown to Cairo when he heard the news.

As the revolutionaries stood their ground for days on end, unwilling to relinquish the small piece of the city they had reclaimed from the political leaders they resented, tensions between them and the military personnel grew increasingly combustable, the stakes began to rise to dangerous levels, and Jehane began to find her story. It’s a story of a new Egypt, written by young people starving for change.

The Square follows the lives of these revolutionaries as they fight to oust Mubarak and his regime, and fight even harder against his replacement, Muslim Brotherhood President Mohammad Morsi, who turned out to be just as corrupt as his predecessor. With jaw-dropping street-level footage, Noujaim captures the energy of the young people driving one of the most significant revolutions in human history.

Noujaim and Amer sat with us in San Francisco to talk about what led to the revolution, the importance of art in this new movement, Egypt’s generational gap, their inspirational cast of characters, and more.

On Friday, January 17th, The Square will be available on Netflix as well as screen in select cities. For more info, visit www.thesquarefilm.com.

A woman in the film says something to the effect of, “Egyptians don’t protest easily.” How extreme was the political and social unrest for Egyptians to flock to the square in such numbers?

Jehane: That was Bosayna Kamel. I made a film about her in 2007. She was a newscaster and she quit, because she said she was no longer going to tell lies. She started an organization called “Egypt We’re Watching You” with two other women. She was the first person I called when I heard rumblings going on. It’s funny you pick her, because she ended up running for president throughout this whole process.

Karim: The first woman to run for president.

Wow. You didn’t feel the need to explore her story more?

Jehane: We decided that she was her own story and didn’t want to go into it in the film. We wanted to keep the film about the square.

Karim: To your question, I think the country had reached a breaking point in terms of piled up frustration and oppression. I think that what sparks these incredible movements that are leaderless is a kind of social phenomena. I don’t think it’s one particular incident that sparked the whole thing. There was a series of police brutality that happened, and one particular case was Kahled Saeed.

Jehane: He was arrested, tortured, and killed. Brutally, brutally tortured.

Karim: The initial protest on January 25th was just a protest against police day. Nobody anticipated that it would be that substantial. The biggest impact wasn’t that people came down on January 25th; people had done that before, many times. Why this situation was different is because people came back the next day. And the next day. And the next day. That’s what made this different than other protests in the past. People were determined to continue, and when they did, the impossible happened. The barrier of fear that people had been living in for years crumbled. It was really magical.

Here’s a people who had lived in a country where no political discourse was happening, where you’re scared you might disappear or get arrested. People from all walks of life came down in the millions, and it was a real paradigm shift for people power and world history.

What Bosayna says in the film is that, yeah, it takes a lot. The cost has been high, but people aren’t going to give up.

Jehane: She also has the right to say that, because she’s been fighting in the streets for so long, trying to get people to understand what their rights are. She’s experienced that people have put up with so much for such a long time. Their rights have been trampled on. Egyptians have managed to live through these difficult periods with a sense of humor that is often difficult to understand, given the dire circumstances.

Karim, is it correct that you met Jehane in the square while you were setting up a stage for people to read poetry?

Karim: Yeah. There was a brotherhood stage and a left wing stage. My cousin and I had set up a stage that was an open mic for people to say whatever they wanted. The only people speaking on the other two stages were leaders, known people. The fact that people could say whatever they wanted–people had never seen that before. It was exhilarating.

So, you have this stage for people to read poetry and speak freely, and now you have this wonderful film that is going to influence a lot of people. Talk about the importance of creative work in this movement, how it can uplift, encourage, and educate people.

Jehane: It’s incredibly important. If you looked around at the people who really stuck it out at the square, a large number of people from the creative industry were there. There were times when things emptied out, and it was always the creatives that were leading change. You could see this demand for change, for people to pay attention and not turn a blind eye anymore, through the uploading of videos, through paintings on the wall, through stencils of the people who were killed spray painted on the walls of downtown Cairo so that the army couldn’t forget what they had done. Graffiti exploded. The only serious political conversation that’s been able to exist has been through cartoons and satire. It’s the cartoonists and satirists that have been able to get away with pushing the boundaries.

Karim: At the heart of this movement is culture and freedom of expression. What’s galvanizing Egyptians are young people who choose to break the narrative and write a new one. That’s part of a global paradigm shift. There are a lot of young people around the world who are now starting to say, “We deserve better.” The successes and failures of these movements around the world are all connected in determining whether we get to that better space that we all know is possible. That’s what we end the film on, this idea of a global conscience, which is what we’re really fighting for in Egypt and what people have been fighting for with all of these social movements around the world. The fight against apartheid, the fight for civil rights in this movement, Irish independence, the occupy movement; all of these movements are interconnected. The best part about releasing the film here and in other places is seeing how people relate to the film who have nothing to do with Egypt.

Has the film screened in Egypt?

Jehane: We haven’t been able to show the film there yet. I had a conversation with Ahmed and Magdy the other day, and I felt so bad because they’re not able to experience the incredible reactions from people. Although, they were incredibly motivated and touched by the audience awards at Sundance and TIFF, which are the only awards that mean anything. (laughs)

One of the many themes in the film is the generational dynamic in Egypt. There’s a big gap there. In one scene, Magdy’s mother is upset with him, saying that he’s running around and “playing” revolutionary. Not much later in the film, Ahmed says that the greatest victory of the revolution is that children have begun playing a game where they “play” revolutionary.

Jehane: What Magdy’s mother said was very much a comment on what the Brotherhood is doing for a lot of these people who are unable to support their families. Magdy has been supported by the Brotherhood for 25 years. It’s interesting that you saw that. For many of the people who fought in the revolution, one of the big victories for people who fought in this revolution is that there’s been a cultural change, a change in consciousness similar to what happened here in the civil rights movement. There may not be all the tangible results that we demanded taking place, and we’re still fighting for some of the demands of the civil rights movement to be turned into laws, but there’s a kind of consciousness that’s changed where we’ll never accept some of the things that we accepted before people stood up and said no more. That’s what’s beginning to happen in Egypt, and it’s crucially important.

You can’t really ask for a better film subject than Ahmed. What’s amazing to me is that you found him and the rest of the crew in the square, all at once. How did that all come together?

Jehane: We all met because we were sleeping near each other in tents. The revolution was very much about using whatever skill you had to help move it forward. So, if you were an electrician, you’re figuring out how to hook up the street lamps so people can charge their cell phones in the square. If you had access to a restaurant, you were bringing food to the square. It was incredible. As a filmmaker, I could film, I could tell stories through images, and I could be a witness. It became a movie later.

I met Karim, who was in the process of redoing the largest hospital in Egypt. If you can redesign a hospital, you can figure out how to produce a film. I met [Muhammad] Hamdy, who is a very talented director of photography, and he helped us figure out the cameras. It was the first time I’d ever used a 5D. Cressida [Trew] came on as one of the filmmakers and decided she was going to film Khaled and some other people. I don’t know whether Khaled knew at the time that that would mean he would be waking up to a camera every day (laughs), but we got very intimate moments with him because of that.

All of the characters we met in the first 18 days. You choose characters by [asking yourself], “Is this somebody that I want to spend the next couple years following?” You have to feel quite passionate about the people that you’re following and that they have important voices to be shared with the world. I felt that about each one. Khaled is incredibly articulate during very confusing times. Magdy is one of the most open-minded people I’ve ever met. Having been raised and deeply committed to the Brotherhood, he was incredibly open to other people’s points of view.

I fell in love with Ahmed when I met him, and everybody does. His joy just emanates from him. His passion, his belief, his principles. That’s something all of the characters share; a steadfast dedication to their principals, no matter what. Ahmed was inspiring. He was somebody who would literally start a discussion in the square and in five minutes be surrounded by 50 people. By following him, I knew that I was always going to be at the center of the action.

There’s a breathtaking shot where the person holding the camera runs after Ahmed as he charges to the front line of a barricade.

Karim: That was the DP, Hamdy. He’s an incredible cinematographer. When you witness the electricity of people claiming their rights and coming together, it just changes you fundamentally. When you witness people being attacked and the state being abusive, it rallies a nerve in you, and you feel like this story needs to be told. Our team that came together all felt that way, that the narrative we started writing as young Egyptians needed to stay in our control. We couldn’t allow state or international media to rewrite the narrative or end it where they wanted. That’s what drove people to put their lives at stake. What you’re capturing is history. What you’re capturing is evidence. What you’re capturing is a society’s unraveling and the founding of a new nation. You don’t care about your life when you’re in that position. You’re witnessing such acts of bravery that you think, “If they’re doing it, what am I doing?”

That’s what’s been great about the film. We show the film to a lot of high school students, and one girl said, “I don’t feel comfortable calling myself an environmentalist anymore, because what am I actually doing for the environment besides posting things on facebook? Am I really willing to take a stand?” That’s been important in the release of this film, to show the importance of the street, how hard it is to affect change, and yet how we all have a stake in world change.

Is it gratifying to be able to show the film to people across the world and see them relate to what’s going on in Egypt?

Jehane: It is. It’s been incredible showing it to high schools and colleges. The youth of this country really get it at a core level. They’ve come up to us and said, “These people feel so alive. I want to feel alive like that.” The film is about fighting for change. It’s a process, and it takes commitment. I’ll never forget when the military put out a law that said protests were banned, and Ragia (a character in the film) was being interviewed by CNN. She said, “We have to protest against this law.” The reporter was like, “But…protests are banned…” and she said, “Yes. We have to protest it.”