JC Chandor Talks ‘All is Lost’, Robert Redford’s Silent Performance

In All is Lost, JC Chandor’s man-at-sea movie starring a 77-year-old Robert Redford, the director takes a dramatic departure from his dialogue-driven ensemble piece, Margin Call, and delivers a moving, intimate piece of cinema that, quite simply, follows a man on a boat as he fights to survive crushing waves, rainstorms, starvation, and all the mental and emotional trials that come along with it. Redford’s performance–which is nearly silent (he only has three lines in the film)–is as captivating as any he’s given, but in a way that’s wholly unique.

We spoke to Chandor about how you must see this film in the theater, his choice to go the silent route, the difficulties of filming a boat capsizing, Robert Redford’s ego, and more.

All is Lost is in theaters this Friday, October 25th.

The film is pure cinema, essentially silent. It’s different than Margin Call on that and a lot of other levels.

Most of my directing up until this point was in bizarrely action-y sports commercials. When I was coming up, that was the only thing that would allow cheap production values. I thought it was a good entry point. I was doing stuff for DC Shoes, Red Bull. Margin Call, as a writing piece, was a chamber piece, basically. I wanted to get out of that, as a director.

Was it refreshing?

It was. It ended up being exhausting and intense. I went a little too far in one direction (laughs). There was also something fun in the way Margin Call was released. I gave in to the fact that it was going to be released day-and-date, because I actually thought it would be better for the film and more people would see it. It can be seen on a smaller screen and still have the same impact. For [All is Lost], that’s not the case at all.

I completely agree.

You have to see it in a movie theater. I love that about it. A lot of the films this fall have that in spirit. They realize that there is something great about the film experience. Not all stories need three years to tell them. Some people’s lives are most interesting just for a moment.

There’s a spectacular shot where the ship barrel-rolls. How the hell did you shoot that?

We had chopped off some of the bottom of [our ship] so it was easier to keel. They basically sprung-loaded it. They were pulling the ship from one side–jacked it, jacked it, jacked it–then essentially had a release. They popped the release, the boat started going, flipping. The whole trick of the movies is that, within any 40 second sequence, there’ll be six or seven totally different locations we use to shoot it. It’s all done like a jigsaw puzzle–it’s post traumatic stress syndrome. I don’t even want to think about it (laughs). We had to organize it, because it was shot out of order. Moment by moment, shot by shot, it was completely out of order. We had my editor right there in the studio and near the port in Mexico where we were doing a lot of the shooting, so I would just check in with him. It was very efficient–I could be walking from one tank to another, one stage to another. I’d just be constantly how things were working and learning what was getting used and what wasn’t.

That’s the only shot that’s blatantly, admittedly a stunt guy swimming up as it’s [rolling]. That’s the one divine intervention moment of the film, where it’s good luck instead of bad luck, but it’s just luck. Bizarrely, most of the people who go overboard and live to tell the story had something weird like this happen. For everybody else who falls overboard–which is, like, 90 percent of them–it ends there. There are these stories where a person will get washed over by a wave, but the wave has such a huge pattern that it’ll sometimes suck you back [to the boat]. People talk about literally being “dead” in their mind, and then being sucked back. We thought that was pretty cool.

Your camerawork is really, really intimate.

The film was totally meant to be that you are just in the moment with this guy. We shot the film in the style of a “bungie cord effect”, as I like to call it. Essentially, we shouldn’t be more than 6 or 7 feet away from this guy, ever. Every shot is eye-level, hovering over his shoulder. You’re always right there. We shot most of the movie handheld. There’s not dolly in the movie because it’s a boat, so you don’t want a dolly on it (laughs). We had a 60-foot Technocrane, and the crazy thing about that tool is, the tendency is to do a J.J. Abrams type shot. He’ll have two or three huge Technocranes all kind of dancing around something, which is beautiful in that context. This film was about feeling you were literally hovering with this guy. The cool thing is, that tool allowed me to hover anywhere in such a quick way. It wasn’t about the tricks you could do once it was there. It was about quickly being able to reach out to a particular spot in the action or follow along with him where you sort of float along. We had these amazing operators. Your tendency is to say, “Now, swoop up and see what he’s doing!” Then, you’d immediately realize, that’s just Robert Redford climbing around on a weird little boat. It took us the first week or two to realize that. The two shots that peel away the furthest are there for very specific informational purposes, like showing the hole in the boat. Besides that, the [camera] is tight.

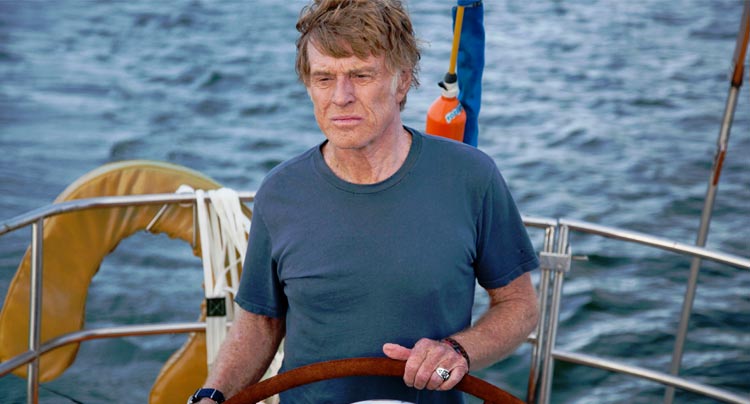

Talk a bit about Robert’s performance. It’s almost entirely physical, and he looks perfect for the part.

Yeah, he’s led that kind of life (laughs). There are tricks that you can do when preparing for a role, frankly, that aren’t plastic surgery or anything, but can make you look better. He could have required me to do things to make him look better, but he didn’t. He knew that that was where I was going with it as a look, and he–at this point in his career–embraced that, which is awesome. “This is what I look like.” It was about pushing himself. He admits–in a joking fashion–that his ego kicked in. He didn’t have to do all those stunts, but once he started to, he liked it (laughs). He’s tremendously fit. He’s so athletic. I think his knees are starting to be a little arthritic because he’s used them so much, but his upper body is fitter than I am. He’s ripped. We built triple rows of handholds into the boat, and as long as he was firmly planted with his hand on something, he was able to do whatever. It was pretty amazing.

In the same way that Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman is about a woman’s work, this film feels like it’s about a man’s work–he’s patching things up, lifting things, fixing things.

The whole point of the film is that what he’s doing is not necessary in any way. The boat serves no function besides enjoyment. There’s a sense of false adventure to the adventure. He gets his adventure, but from that point forward he’s kind of stuck in it (laughs). I would question to call it “work” in only that the fact that it’s all forced was pretty integral. It’s strictly about survival in its most basic form. There’s no other purpose to it.

I love the first line in the film. Do you think what this man does in the film is worth anything?

Yeah, I do. He says, “I fought to the end. I’m not sure what that’s worth, but know that I did.” I think, for him, making sure people knew that he fought to the end was very important. It is for me, too. It’s certainly my relationship with life and death being worked out in the film.