Jason Cohen and Tom Christopher Talk Facing the Fear of Forgiveness

Facing Fear, a short film by Bay Area resident Jason Cohen, just got nominated for the Oscar for Best Documentary Short. It explores the nature of forgiveness through the story of two men, Matthew Boger and Tim Zaal. One night when a 14-year-old Matthew, who came out at a young age, was roaming the streets of West Hollywood, he was jumped in an alley by a group of punk neo-Nazis and beaten nearly to death. He remembered one of the persecutors clearly. 26 years later, he and Tim (who had now left that terrible lifestyle behind) met again, and were faced with the impossible challenge of forgiving another (Matthew) and forgiving oneself (Tim). They began doing presentations across the country about the incident and how it affected their lives, and face the fear of forgiveness to this day.

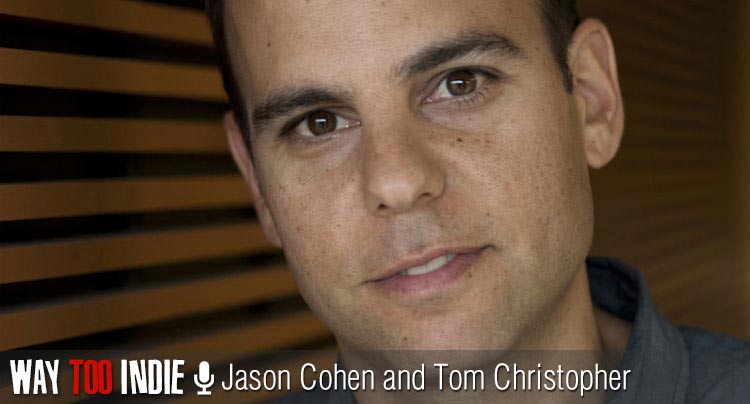

Cohen invited me to the Saul Zaentz Media Center in Berkeley, California, where the film was produced (it was shot in LA). In a building where a slew of great films were worked on (One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest, Amadeus, just to name a couple), I chatted with him about what’s so scary about forgiveness, giving a former neo-Nazi skinhead a fair shake, the advantages of the short film format, Matthew and Tim’s relationship today, representing the Bay Area at the Oscars, and more. Following my interview with him, I spoke with editor Tom Christopher about his experience with the film, which I’ve included below.

For more info, visit facingfearmovie.com

Talk about the relationship between fear and forgiveness.

Jason: We named the film Facing Fear, and when you hear what the film is about, the first, obvious notion is of the victim, Matthew, facing this fear of meeting his perpetrator, which was obviously part of it. But, for us, the rest of it was facing the fear of the process of forgiveness and everything involved in it. It can be scary, and it was scary for both of these people, the victim and the perpetrator, equally. When you hear stories of forgiveness, you’ll tend to sympathize with the victim and assume that they’re bearing the burden of this process of forgiving. We wanted to clearly show that Tim was facing plenty of demons and that the process was as difficult for him as it was for Matthew. Maybe even more difficult at times.

I feel that typically when people see someone like Tim, who’s done what he’s done, they think “monster”. It’s fascinating that half of the movie belongs to him.

Jason: When we started filming, they’d been back in each others’ lives for about six or seven years, so they had been on this journey and were in a good place. They’ll both admit that it’s something they still struggle with today, but for Tim, I feel like he’s struggling with it more. He has other things going on in his life that are still a direct result of his past life, and he’s got a lot of guilt. As he says in the film, there’s an inner struggle that he’s having, forgiving himself for that person he used to be. Matthew has personal issues, too, but Tim’s a really complex person.

I think you said it; when people [learn about] Tim, they think “monster”. But when you meet him, he’s a teddy bear. He’ll admit it. He loves to talk, and he’s very outgoing. You would never–aside from the fact that he’s 6’3 and bald–have any clue that he could have been leading a life like that before. It just wouldn’t cross your mind.

Was your intent from the beginning to focus on both Matthew and Tim’s perspectives equally?

Jason: The intent was that we wanted to show that the process of forgiveness is a two-way street. We wanted to show both of their stories equally. If you sit down and watch the film, they have about the same amount of screen time, which was intentional. We wanted it to come from two perspectives and show that it wasn’t just one person’s story. We wanted to show the impact they had on each other.

The word “forgive” gets thrown around a lot these days, but I feel like most people find it hard to truly forgive.

Jason: Matthew has said, “forgive but never forget”. He doesn’t want to forget what happened. It’s part of him. It’s part of his fabric, and it got him to where he is today. Even though he’s forgiven Tim, it’s always going to stick with him. I think Tim would like to forget it a little bit more. [The incident] defines them a little bit, even though it’s not necessarily what they wanted to be.

Philomena has a similar theme of forgiveness to your film, though that message seemed to be lost on a few of the people I saw it with in the theater. Your film gets straight to the point and examines forgiveness very clearly and concisely. The theme won’t be lost on anyone. Is this an advantage of the short film format?

Jason: We knew we were making a short film the beginning, so our goal was to tell the story in as complete a way as possible in this short window, but still have an arc to it so that the viewer is entertained, for lack of a better term. We wanted to hit on the key elements of each of these subjects’ lives that advanced the story. And then there was examining this forgiveness process and coming to this resolution that is where they are today. Nowadays, with short films, people are seeking them out. Part of that, unfortunately, is that people aren’t going out to theaters to see films as much.

If you’re watching a film on your laptop, cell phone, or iPad, you’re much more likely to watch a film that’s 30 minutes or less than one that’s 90 minutes. It’s how it is, and we recognize that. We want everyone to see our film on the big screen; we worked so hard on it to make it look how it looks, to make it sound how it sounds…we cringe when we think of people watching it on their cell phone. But, our ultimate goal is to get the film out there so that everyone can see it. We have a nice open and get into it in the first five minutes of the film to really suck people in, and if we can keep them…then that’s great. (laughs)

Talk about that great opening voiceover. It’s really compelling. Tim says…

Jason: “I don’t know if I could forgive somebody the way that he’s been able to forgive me.” We start the film with that to say, “this is a film about forgiveness, just so you know”.

When Tim and Matthew started doing their presentations, they weren’t even close to making amends, right?

Jason: We didn’t want it to seem like they were forced into [working together]. They weren’t ready. They weren’t comfortable with each other yet, but they did it. In retrospect, it helped, and it advanced this process that they were in. Matthew would talk about that, just being around each other, stuck on a plane or a car to go to one of these presentations, they just had face time, which is what they needed. They needed to get to know who the other is now as opposed to 26 years earlier. The process of forgiveness isn’t a cut-and-dry thing; it took them 5-7 years to get to where they were.

Their first encounter kind of defines their relationship. What’s fascinating is that these days, Matthew and Tim often only connect when one or the other is going through a hardship. They help each other through it. It’s like their relationship can only operate at a heightened emotional level.

Jason: They’ll readily admit that they’re not buddies, hanging out on the weekends. They lead very different lives. But they both know that when life is tough and they’re dealing with issues, they can pick up the phone and call the other person. Neither of them had that support structure before, especially Matthew, who was homeless on the streets and didn’t have the support of his family. He’s been able to have Tim as a confidant, [and vice versa]. It’s funny, when they do their presentations, they specifically make a point not to talk beforehand. They want to do it fresh. The way they do their presentations is they just show a short video about their story and open it up to questions.

Was the goal of the film to show that people can forgive in even the most extreme scenarios?

Jason: Not necessarily. We tried to take as objective a look at this story as we could. We’re not saying we want people to forgive or that it’s the right way to go. The goal is to have people talk and discuss, take it back to your own life, and figure out how it plays into your own situations.

Perhaps someone could never forgive what Tim had done.

Jason: Right. We’re not telling anyone that they should. It all depends upon the person. I can’t tell somebody who’s been through something even more horrific than this to forgive. I don’t know what they’re going through. To tell people that “forgiving is the answer” was definitely not the goal. A lot of people have taken that away, and we’re happy! But some people have said, “No. I could never forgive that.” We say, “Great.” As long as they think about it.

Fruitvale Station didn’t get any Oscar love, but the Bay Area’s got you representing for us at the show!

Jason: We’re totally happy that we can represent the Bay Area down there. A lot of people don’t realize that it’s a Bay Area film because it’s all shot in LA. Everything else was done here in Berkeley. It’s not on local people’s radars, but we’re trying to remind them.

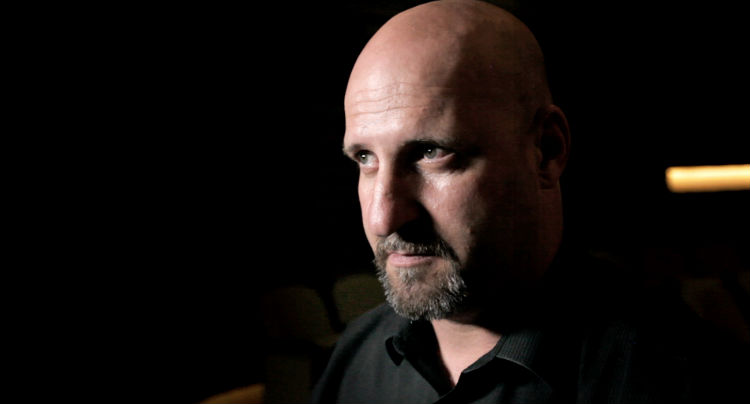

[After my chat with Jason, he took me to the room where they edited the film, and I caught a quick interview with editor Tom Christopher as we sat in front of the very equipment he used to make Facing Fear.]

Now that the film has been nominated for an Oscar, how has it changed your schedule?

Tom: First of all, it’s very cool for it to have happened. It’s not something you ever count on or expect. A lot of people have been coming up to us, sending us texts, emails…it’s just been a really heightened sense of communicating with people I maybe haven’t talked to for years.

So you’ve reconnected with people through the film?

Tom: Yeah. People have heard the news, or they want to see the film, or they’ve seen it. We’ve been in about six festivals all over the country and in Amsterdam as well. It’s been interesting. Both Jason and I have reconnected with old peers and friends.

How did you react to the film personally?

Tom: This film would affect me differently every time I saw it. I haven’t worked on it for months now, but I would screen it for people occasionally. I would find that a different part would affect me each time. “This is the part where I’m getting really involved in the story, today.” There are little nodes throughout the film that can grab you. It’s a human story where you can be very empathetic to the people you’re learning about, even though they’re very different from you.

Talk about crafting the film and making it equal parts Matthew and Tim.

Tom: We were really trying to create a single voice. That’s what’s really happening. It’s not just Tim’s story or Matt’s story–it’s coming from a single voice. In editing, I tried to make it so that the men were interrupting each other, cutting each other off while they’re talking. If you were looking at this in film school, you might think, “This guy made a bad edit here!” What I’m trying to do is have them interact in some way, sometimes visually. In an interview, you’re not dealing with visuals that often, but when I was able to do it, I did. There were certain cues that would cause a place to be a great edit. Sometimes it’s a visual cue, like something they’re doing with their hands or their face. If you can interact that way, you build this unified voice, I think.

Was there ever anyone who had a problem with the film giving a voice to Tim?

Tom: On a film like this, you’re working on a very big issue, I think. I’d bring it home with me, and I’d talk about it at dinner. I’d have a lot of interesting conversations with my wife and guests at dinner. They’d ask, “How can you make this work? There’s no way!” I thought, my work is cut out for me. I can’t even get my wife to agree that I’m going down the right path. I realized that there was going to be a lot of resistance to this story, right from the first week I started working on it. It’s not a spreadsheet kind of job; you don’t put things in columns like, “I want 30 seconds of him here, now I want 35 of him.” It’s all about feel. It’s like a piece of jazz, like you’re playing an instrument.

There’s a musicality to editing.

Tom: I tap my foot when I edit. I just do. It’s a natural thing. I’m grooving with the piece. I’ve actually been in movie theaters where people say, “Stop doing that!” I get lost in the moment. This is a job that involves timing. Everything’s timed. What you’re trying to do is find a groove for the piece. The way you do that is with the pace of the cutting and the nuance to how you draw someone into what’s going on. It’s not easy. You have to be experimental.