Interview: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders of The Out List

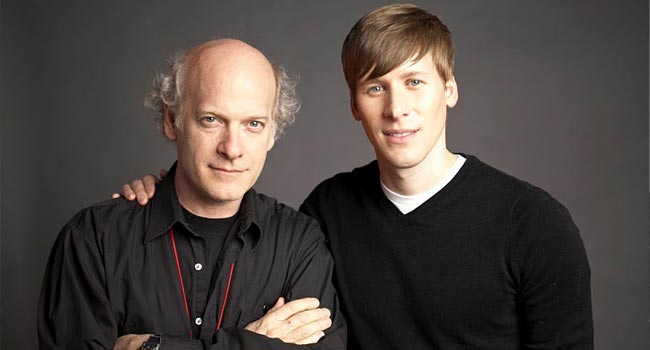

Director/photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders has pointed his camera at some of the most famous and important people in the past 50 years—Barack Obama, Alfred Hitchcock, Hilary Clinton, Jimmy Carter—and his portraits have been featured in the Museum of Modern Art and Vanity Fair.

In 2008, he launched an HBO documentary series called The Black List, in which African Americans are stood in front of a blank (beautiful) backdrop, and simply share their life stories with us, face to face. The documentary earned much praise and was followed by two more entries, The Black List volumes 2 and 3. The project was expanded further with The Latino List and now Greenfield-Sanders aims his lens at LGBT Americans in The Out List (premiering tomorrow night at 7:30 on HBO).

After an electric screening at San Francisco’s Castro Theater last night for Frameline37, on the eve of the Supreme Court ruling on the constitutionality of Proposition 8, Timothy sat with us to talk about his filmmaking process and his thoughts on this important time in gay rights history.

One of the major topics of the film is gay visibility in America. Do you think the LGBT community is represented adequately on television and movies, or do we have a long way to go?

Television has become a place where America—between New York and Los Angeles…that America—get to see gay people much more than they ever did and get to understand them better. Television is very powerful that way. But…there’s so much more to do and so many more people to turn around. That there needs to be a Supreme Court case right now depresses me.

When you live someplace like San Francisco or New York, it’s easy to forget how much of America is unfamiliar with the LGBT community.

The last ten years have been so extraordinary. I came to New York when I was 18 in 1970. It was a year after Stonewall. If you step back and look at what’s happened in 44 years, it’s tremendous. The days when I was a kid in New York…the idea of gay marriage was…nobody even imagined it! It was so off-the-charts. Today, it’s very common in people’s heads, even though some people aren’t used to it yet. It’s part of the dialectic.

Media has played a large part in that.

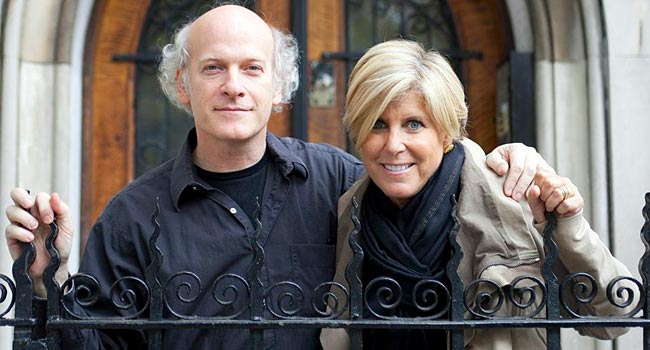

Yeah. You look at this film, and there are famous people in it who are as famous as anyone in the world. Neil Patrick Harris is a hugely important television star who’s publicly out. Suze Orman, Cynthia Nixon, Ellen [Degeneres]. I think it makes a very big difference. It’s a big deal.

The cast you’ve assembled is incredible. You’ve included famous people, but there are school teachers, playwrights, and drag queens given the same platform to tell their story.

It’s a very difficult thing to pick 16 perfect gay people (laughs). We did it!

You did!

I’ve been making films for a while, so I have other films we can send to people so that they can see the seriousness of these films and understand it’s going to be on HBO. But, it still takes six months to get someone to sit [in front of the camera] for you. It’s very hard.

Wanda Sykes says in the film that her simply talking about her wife and kids during a comedy bit is a statement for gay rights in itself. She doesn’t have to make any type of declaration—living her life in the public eye is declaration enough. This film, on the other hand, addresses the subject quite directly. The subjects are looking straight at the camera, straight at us.

The concept of the “direct-to-camera” interview—which I started doing with The Black List—seems so simple. Today, you look at a GAP commercial and they do it, the Oscars do it. All of it is “direct-to-camera” because it’s so powerful. In 2008 when I did it, Errol Morris was the only one who was doing that kind of filmmaking. My still portraiture is all about this feeling that you get looking at someone looking at you. I knew I could convert that into film and it would work.

Fortunately, everything I needed collided at the right time. The right camera—which a friend of mine had invented. I used it for something and I thought, “Huh, that’ll work.” All the right things happened. That’s why The Black List was so successful. In 2008 you didn’t see films like this. On top of that, if you had gone to a network and say, “We’re going to do a film and there’s black people talking directly to camera and there’s no cutaways except maybe a photo here or there and that’s it.” they’d say, “You’re crazy, it’s bullshit, it won’t work, it’s boring.” It’s anything but boring.

Talk a bit about your aesthetic. You’ve done everything there is to do in terms of photography. You mentioned that you needed that camera to be invented. Was technology holding you back from achieving the image you wanted?

No, it’s just that…I was a filmmaker before I was a photographer, so I’m very aware of the technology. I wanted to have two cameras, but I wanted [the subjects] to look into the cameras. A friend of mine had made this camera for some other use, a single camera. I said, “Can we put two cameras there? I need to edit this.” I need to be able to cut between the close-up and the medium shot, because people don’t speak perfectly. That’s what editing is for.

I asked Toni Morrison to sit down for [the camera set up]. She was a friend of mine for 30 years and I had been shooting her portraits forever. I said, “Toni, I have this idea to do this film about African Americans. I’m not sure how it works, but I need you to sit in front of this camera and we’re going to do an interview. Will you be a guinea pig?” and she said yes. I also did it with Thelma Golden, who’s a museum curator. Those two gave me the confidence that “this works.” We edited [the footage] and it became my trailer to raise money.

You’ve been doing the List series for about six years now. Have the aesthetics changed at all, or are they essentially the same?

The people change.

That’s enough.

Yeah. It looks so simple. You watch this, and you think it’s just people talking. But, every decision I made [about the aesthetics] from the beginning…If I had made one decision incorrectly, it wouldn’t have worked. Do I change the background color [for every subject]? Do I move the lights? Do I ever cut to an interviewer? We did it a certain way and I knew not to touch it. It’s perfect. I’ve done it with people who are not that interesting, and it makes them so much more interesting! (laughs) It’s something about the immediacy. You feel a connection to the person. On top of all that is very good editing.

When filming, do the subjects see a camera or do they see a person?

They see a teleprompter with Sam’s (McConnell, the interviewer) face. They’re just looking at a kind of ghostly face. Sam sees the same thing. After a few minutes, you get used to it and your talking to this face which is reacting in real time to you.

You can really feel that in the film.

You can try having people look into the camera while you stand next to it, but they always end up looking [at you]. It doesn’t work. It’s not cheap—it’s an expensive thing to do.

It pays off. Let’s talk about this screening here at the Castro Theater. What a warm reception!

I was nervous that we wouldn’t get anyone here because it was at 4:30 in the afternoon (laughs). It was an amazing audience. It’s a very gay city, a very political city. To show at the Castro is a big deal.

We’re on the eve of history, with the Supreme Court ruling on Prop 8 coming tomorrow.

I’m nervous about tomorrow and I’m hoping for the best. It’s hard to believe in 2013 we’re even talking about these things. We shouldn’t be waiting on a Supreme Court ruling on whether people should have equal rights. It’s insane.

If the decision goes the gay community’s way, will it feel like a victory, or are you thinking, “We should have already been here”?

It’ll be a victory, but it’s not enough. There’s so much wrong. Where do you start? There’s never a definitive victory.

You’re doing some great work with HBO, putting out films that can help change the world.

I feel very lucky. I’m 61 years old, I had a great career as a photographer, I was able to—as digital technology was destroying photography in front of my face (laughs)—combine digital technology with filmmaking. I’m very fortunate. HBO…there’s nothing like it. They support films that would have no audience without them. They would never get made. They need to give Sheila Nevins (president of HBO Documentary Films) the highest medal there is in the United States. She deserves it. She’s done so much for all kinds of people, not just gays, blacks, or Latinos. If you look at the films she’s produced and helped to get made, it’s remarkable.

The List series has become a brand in a sense, and that’s an amazing thing as a filmmaker, to turn a style of film into a brand. I’m proud of that. You never run out of interesting people. In that way, I’m very lucky. There’s always someone new, always someone who’s been forgotten and deserves attention. These films are able to put someone like Wazina Zondon, who is a school teacher in Brooklyn, on the same level as Ellen Degeneres. They each have an important message.

The Out List premieres tomorrow night on HBO at 9:30

Update: The Supreme Court ruled the federal Defense of Marriage Act, which defines marriage as a union between one man and one woman, is unconstitutional. A win for Gay Marriage.