Robert Kenner On ‘Merchants of Doubt’, The Art of the Lie

Climate change has been a hotly debated topic for many years, with scientists and researchers and global warming deniers vehemently arguing their points on national news channels. Robert Kenner’s new documentary, Merchants of Doubt, investigates not the arguments on both sides of issues like climate change, but the deceptive tactics utilized by PR people, working for big corporations, who pose as so-called “scientists” on television, tricking Americans into believing whatever “truths” are most lucrative for their employers. People were deceived about the health risks involved in smoking cigarettes for years. How could we be so gullible for so long? Because these “merchants of doubt” are some of the most clever people on earth. With hope, the film’s exposition of their deceitful tactics will help lower our susceptibility to the lies they’re shilling.

In San Francisco, we spoke with Kenner about the misconception that the film is about climate change; Marc Morano’s shocking candor in the film; the art of making docs entertaining; shooting on a Phantom cam; and more.

Would it be fair to say that the biggest misconception about the film is that it’s about climate change?

Yeah. I battle that all the time. It’s not a film about climate change. It’s about the “playbook.” Climate change is the big payday, and that’s where all the people have gone to. You hit it on the head. [The “playbook”] goes from one industry to the next. Energy is where the money is at the moment. It used to be tobacco. The movie’s really about how these guys create doubt. It started with the tobacco industry. They knew in the ’50s that their product killed customers. It’s tough to sell a product that kills customers! They knew they couldn’t say, “It doesn’t kill [people]”; they had the facts. But doubt was their product. Anything they could do to cause doubt helped create delay in creating legislation. They did it decade after decade. When there would be studies about lung cancer, people came out and said, “Maybe parrots are causing lung cancer,” or something like that. Scientists would pursue what they were saying as if there was some legitimacy to it, and you can see this from one industry to another. They’d keep coming up with alternative things to study, and then rule out. The purpose was to create doubt and delay, and if that didn’t work, they’d attack the messenger. It’s the same pattern over and over again. It’s really their playbook that’s the story we’re telling. And we wanted to see it through the eyes of the people we’re talking about.

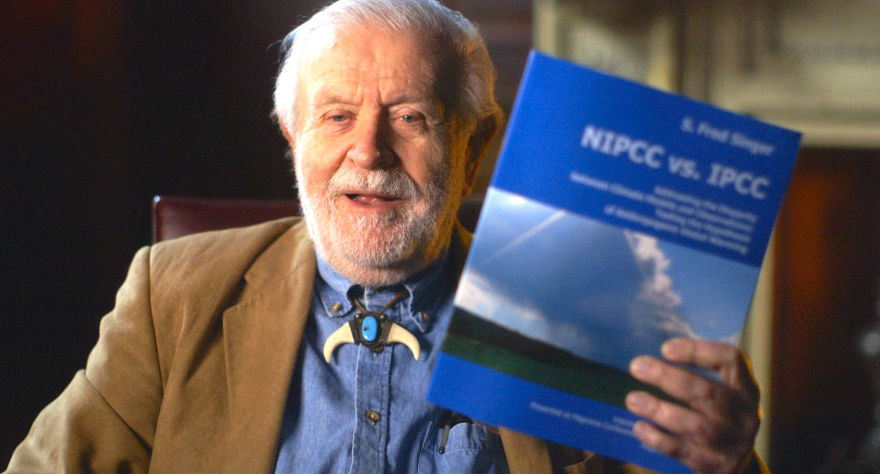

Marc Morano is an incredible documentary subject.

And he’s honest! He’s a totally honest guy. He’ll tell you how [creating doubt] works and how they do what they do. He’s an incredible subject. I know people who totally disagree with him, but then become charmed when they meet him. It’s hard not to. But when you put him up against the damage he’s causing, you judge his words a little differently.

He’s got such a magnetic personality.

[Shooting with him] was by far the most fun I had on this film. I’m still amused by him.

Your film resembles other docs that have a message about change, but it’s different in that it’s not confined to a current event or issue, telling people to take action right this minute. You could apply the principles at play in the film 50 years down the line, I’d imagine.

I don’t think this is a “do this now” type of film. It really isn’t. Maybe that’s not satisfying to some people. It’s about a pattern by which industries and ideologies work. It’s going to be going on in 20 years, and it’s been happening for a long time. Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays, came up with the idea of PR and propaganda. He was hired by cigarette companies. Women weren’t buying cigarettes. He heard there was a suffragette march. Just as the women went by the reporters, they took cigarettes out from under their jackets and started smoking. He called them “torches of freedom” and said cigarettes were about liberation. Then, he was hired by Woodrow Wilson to get us into WWI.

Which would make you happier: if your film entertained people, or if it caused the country to be a little less susceptible to bullsh*it? I’m willing to bet both will be true, but I just want to gauge your hopes for the film.

Oh, wow. This is a “Sophie’s Choice” moment! [laughs] People say I’m such a social activist and a hard-hitting journalist. But I’m also a filmmaker, and I take pride in my craft. I also like to be entertaining. But it has to be about something. In a funny way, the hardest subjects—getting into film talk here and avoiding this very difficult question [laughs]—are social issues. It’s more fun sometimes to take things that are off the money, and then put social relevance into them, as opposed to this movie and Food Inc., where they’re on the money and then you have to take them away from being too on the money. I have to work backwards and try to make it amusing, as opposed to adding some content into something that is amusing from the get-go. I did a film with Richard Pierce called The Road to Memphis, about blues music, for the Scorsese blues series. It was nothing but fun, but it’s also about these other issues that are underneath it. In a way, that’s kind of easier than tackling things straight on. People don’t like medicine; it doesn’t solve the problem. Hopefully you make an entertaining that can change people simultaneously. I don’t think you can change people if your film’s not of interest. In a way, they’re connected.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. For me personally, I don’t always necessarily consume movies for fun and entertainment. Sometimes it’s educational, sometimes it’s cathartic, and sometimes it’s masochistic, frankly. Would a film industry landscape in which your films didn’t have to be “entertaining” or “fun” to be successful be appealing to you?

We have to define entertaining. This movie isn’t a “yuk-yuk” situation. Adam Curtis made a film called The Century of Self, which I found incredibly entertaining, but it’s just a narrator over archival footage. It’s not what you’d call entertainment, perhaps, but I find it entertaining. It comes in lots of forms, but it has to intellectually engage you. There was this European film about food from about five years ago that was just images. I don’t even know if it had music. It was just sounds. Sometimes I think I use too much music in an effort to make it a more engaging movie. But then you go to the Berlin film festival, and some of these documentaries have no music. I saw Ida recently, and it’s incredible. There’s nothing except the source music in the film. So sometimes I think I’m trying too hard to be entertaining. Am I trying to make up for something with music? I love my composer Mark Adler’s music in the film, in our next film we’re talking about using more industrial sounds and maybe making the music organically grow out of those to where you don’t even know it’s music. I think it’s wrong to tell people what they’re feeling, which is what music does sometimes.

I found it hard to walk away from the film and not admire how talented these spin artists are, despite the questionable morality of their work.

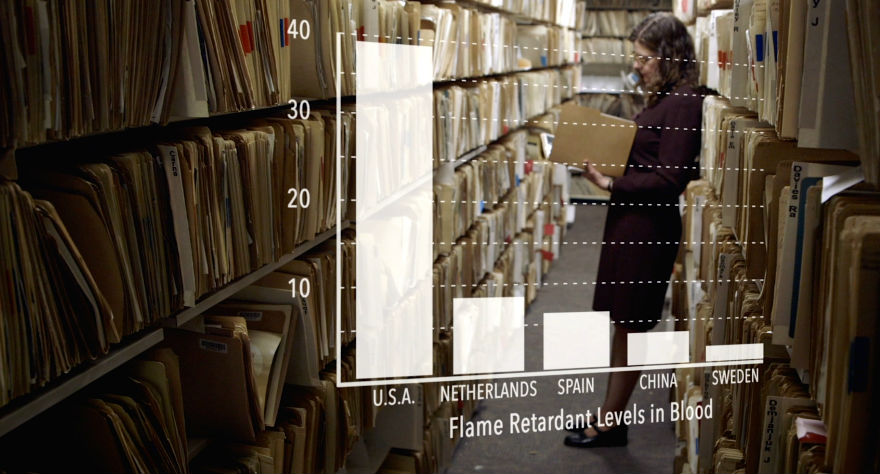

I’ll give you a story. Peter Sparber is the guy who worked for the tobacco industry and when confronted with the problem of house fires in the ’70s convinced people that couches were what started the fires, not cigarettes. He got it to where there was a law stating there had to be fire retardants in couches. Turns out, the retardants cause cancer. But [pulling that off] was very clever [of him]. He would never talk to reporters, never return their calls. I said to him, “You’re so good at what you do. If you can do tobacco, you can do anything.” He said to me, “Robbie, I never call reporters back,” and I said, “I know, I’ve heard. I’m shocked you’re calling me” He’d seen a lot of my movies, and he started talking about them. He said, “I’m writing a tell-all, and I have a very major director [attached], but it’s not working out. Maybe we should talk about it.”

I said that I was making a movie, and that it wasn’t just about tobacco, but about other things like climate change. He said, “You know, you could take James Hansen, the world’s leading climate scientist, and I could take a garbage man and get America to believe that garbage man knows more about science than James Hansen.” I thought, that’s scary. I called some reporters and said, “Guess who called me!” They said, “Boy, did he sucker you, Robbie!” [laughs] The guy is good.

You talk about the tobacco stuff. That was a long time ago. Has the advent of the Internet significantly changed the playbook, or is it the same as it was 50 years ago?

I’m sure there are different things that you do, but ultimately it’s the same playbook. There are different mediums to go after. There are certainly less investigative journalists, and there are more PR reps working for industries they used to investigate. That’s a change. But the playbook is the same playbook. There will be new mediums to come in the future, and they’ll figure out a way to take advantage of it. It’s like advertising; you go where the eyeballs are.

At first I thought, well, the Internet gives skeptics a larger platform to stand on and reach the masses. But after I saw the film, I thought maybe the internet isn’t as significant a tool as I thought, in terms of deterring deceptive PR tactics.

Also, how do you know who to believe on the Internet? There used to be Walter Cronkite, one voice that was trusted by most of America. It’s splintered off into many voices, and it becomes harder and harder to know who to believe. But on the other hand, there’s more information available to us than ever, so there’s a good side and a bad side. I feel the life of the playbook will live on.

The movie opens with a magic show at the Magic Castle, and I was so excited. I love magic! It was not what I was expecting at all.

I hoped to fool people! [laughs] It’s not what you think it’s going to be. We did that with Food, Inc., too. That movie opened with that Tim Burton-like scary music, sort of like a kids’ horror film, and this one opens with Frank Sinatra and “That Old Black Magic,” like you’re going to get taken on a ride. And in a way these merchants of doubt take you on a ride. They’re really good, but at the same time, it comes at a cost.

Magic is a great metaphor.

An example of how it works great is when Glenn Beck says to Steve Meloy, “Are you in bed with big oil? And if so, how good in bed are they?” Meloy says, “I’m just trying to do the right thing.” Meanwhile, he’s getting paid huge bucks by coal and oil and tobacco and every product that needs someone to go out there and shill for them. Then, we go to Jamy Ian Swiss talking about how three-card monte works, and he’s saying, “It’s not only how quick the hand goes; you need to have somebody there to work with you who’s winning to create the illusion of confidence.” I love when he says that the word “con” comes from “confidence.” That’s what I think these guys are doing, creating the illusion that they’re independent and looking for the right answers.

The metaphor came about halfway through the movie. We were saying to each other, “These guys are like magicians.” You say it enough times, and all of a sudden it’s like, “Wait. Let’s get a magician!” [laughs] We needed something. At one point it was going to be this meta story of, “How do you make a film about something nobody wants to see?” At one point I was filming with George Schultz, Reagan’s Secretary of State, who believes climate change is a really important issue. I figured, before he could sit in his seat, I’d ask him how I’d do this, and I’d interrupt him all the time. He’s such a stately, wonderful gentlemen, but kept saying, “Slow down! Give me a chance to talk! Don’t mention climate change!” [laughs] It’s really funny, but it just didn’t work. Another time we thought we might do a comic book novel throughout the film, but the magician just tied it all together.

You’ve got a killer credits sequence, too.

I’ve grown to really love credits. Someone said we were the Saul Bass of documentaries. [laughs]

I assume you worked with a digital effects company for the playing card effects.

Two, actually, because we switched in the middle. Every one of those companies has the word “big” in it, like these Astroturf groups that have “citizen” and “freedom” in their names. All the animation guys have “big” in the company name. It was BigStar NYC and Big Block in Orlando. BigStar did our Food, Inc. credits.

The effects look great.

We used a Phantom camera at 1000 fps.

It must have been fun.

It was incredible. Halfway through shooting, a tech person said, “Do you want to go to 1500 fps?” I didn’t know there was 1500! [laughs] To play footage of a guy spraying cards back at 1500 fps would take eight minutes, so it would take forever to see one take. At some point, we switch from the actual cards to the animated cards. I love animation when you don’t know what’s real and what’s not.

Your approach to the graphics seems very different in this film compared to Food, Inc..

I wish we had more opportunities [for graphics] in this film. We had stuff at the beginning, but not so much at the end. I would have loved to come up with something at the very end, which I didn’t. I couldn’t quite figure out what it was. In Food, Inc. we used the graphics for humor, whereas in this film our characters delivered the humor. Morano steals the show. I didn’t need to carry the same weight with the graphics like I did in Food, Inc..

There’s that funny moment where James Taylor is talking about being a “scientist” as a woman on a motorized cart bumps into something in the background.

We watched that, and we’d crack up [in the editing room.] We’d show it to people, and no one would laugh. Then, we put his name on the screen, right where the woman was, and everyone cracked up.

You’re directing the eye.

Like the magician. Like the deniers.