Interview: Joshua Michael Stern of jOBS

The inevitable first wave of Steve Jobs movies is upon us, and it’s no surprise so many studios and filmmakers are salivating at getting their version of his story projected on screens across the world; Steve Jobs is one of the geniuses of our time, somewhat of an enigma, and has changed the world with his ideas. Director Joshua Michael Stern has the enviable (or unenviable, depending on how you see it) position of having his take on Jobs’ story, jOBS, be the first of many to hit theaters. He chatted with us about the pros and cons of being first, whether Jobs was a good person or not, what made Jobs so frustrated all the time, Ashton Kutcher’s approach to the iconic role, and more.

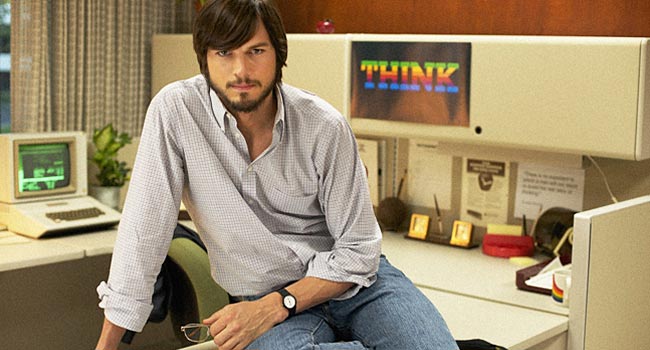

jOBS, starring Ashton Kutcher, opens in theaters this Friday, August 16th.

There have been a lot of filmmakers and studios clamoring to make a Steve Jobs film. Did you feel any pressure being the first out of the gate?

I did. You know, it’s really hard to be the first one out of the gate, but we really did rely on a lot of what was known about him, which is not very much—he was a true enigma. To be the first was a very scary thing, but this entire project was frightening.

Did you want to be the first?

I think it was important to us when we started, but that wasn’t the goal. It just happened quickly, and we knew that it was important to make it happen because there will be other people making these movies. It was scary, but for me, if it’s not scary, it’s not worth doing. If it was going to fail, it was going to fail big! [The film] was ambitious, but a lot of fun and really rewarding.

It is ambitious, and I think one of the smartest choices you made was to not concentrate on the Steve Jobs we’re all familiar with, but instead showing us how he got to be that man.

That was the intention, showing his early 20’s to his late 30’s. [The story] stops a couple years before the first iMac—that blue, translucent pod-like computer that became known and people associate with Mac. For me, it was everything that happened before that—the prehistory, what it took for him to get us there, the adversity that he encountered, and the fact that a man with less fight and vision would have given up. It was a very dramatic story and it had all the hallmarks of a great drama—the villains, the palace intrigue, and the emotionally wrenching moments that you look for in any movie—but this was really his life. It’s a movie, to me, about a man who has an epiphany about what he wants to do. He never separates from that product again. He becomes one with Apple. He becomes Apple. It becomes his obsession, and this is a movie about obsession as well.

After getting to know Mr. Jobs through your research, do you think he was a good person? Or is this an irrelevant question?

I think it’s subjective. If what you define “good” by is someone who shows love by giving the world products that he loves and he thinks will make their lives better, then he’s a wonderful person. I think that’s what he wanted to do from the beginning. He was sincerely, in my opinion, that man. He cared deeply about what he was giving people.

One of the things that became very obvious to me, especially when he was younger, when he first started the company, was that people told me he had a really hard time explaining things. This is from a man who’s known for his keynote speeches where he speaks brilliantly. He was trying to articulate technology that didn’t exist, but he could see it. It’s like a musician who’s like Bach, but he’s never read or knows anything about music, but he wants to explain the Aria to musicians who don’t know what he’s talking about. He’s said many times in his interviews that things were “obvious”, but to others, things weren’t obvious, and that would breed frustration, and that frustration was evident in everything that he did. He was very rarely wrong, but it took so much and was so expensive to give him the things he wanted. It’s still true, by the way. Mac products are still expensive.

I’ve often thought that the greatest symbolic realization of Steve Jobs’ dream is the iPhone. I was at a lunch somewhere where the busboy—who makes under five dollars an hour—and a multi-millionaire eating at a table both had an iPhone. It was the leveler. It was his technology in the hands of everybody, from the poorest to the wealthiest person on earth. A billionaire probably has an iPhone, and his gardener probably has an iPhone. The big obstacle when he was developing all this technology was to be pure within himself to do all the research and development internally, and not do it like every other company does it—including Google, including everybody—where they just buy a company that has spent all that money, done all that research, and incorporate it into their own. He did everything internally.

There’s a great sequence just after he receives the news that he’s about to be a father and tells the mother to fuck off, basically. He has a private breakdown in his bedroom, seething and looking almost monstrous. Talk a bit about Ashton’s performance.

I can’t say enough about Ashton in this movie. He was so committed to this role since day one. He researched the role and lived the role. He gave himself to this part and this movie in a whole, complete way. It’s a difficult role to live in because Steve was a very conflicted person. If you’re going to play him, you’re also going to have to fall in love with him, because you’re going to have to justify his actions, some of which were not popular and not kind on the surface. [Everyone has things that] are eccentricities to everybody else, but to us they make sense. That’s the truth about all of us, and nobody more than Steve Jobs.

I really constructed that scene to represent the fact that he felt, but he couldn’t communicate. He couldn’t quite tell his girlfriend what was really going on with him, but when he left the room, you could see it broke him apart. That scene that you pointed out—and you’re the first to do it, so I’m glad you did—is pivotal for me. It’s the moment where he becomes “Jobs.” He goes from being this hippy to letting go of his past, letting go of the girl he’s dating, letting go of Daniel Kottke—who he never speaks to again—and symbolically letting go of Steve Wozniak. He becomes what he needed to become. He puts his hair to the side, and…BAM!

So that’s the moment.

That’s the moment. To me, that scene and when he’s crying in his father’s arms are sort of bookends to that period of his life. That was a very important moment. Ashton just went into the room, and there was just a cameraman, nobody else in the room with him. We talked the scene through, I gave him certain things to hit, and he would just do it. It was great.

I like how you show a close-up of him sort of frantically adjusting his belt.

We put a lot of the mannerisms of Steve in the film. I could spend a whole movie shooting Steve Jobs’ hands and crazy-focused eyes. But yeah, those were little anxious, obsessive things he used to do with his fingers. I’m glad you mentioned that scene. It’s a great representation of Jobs. He spoke to his girlfriend, he wanted to make his reality the truth—which was that he wasn’t a father—so he just walked into a room, broke down, and then brought himself together, coming out of the next scene sort of realized. To me, it’s like an origin story where he puts on his uniform (laughs.)

Was Ashton comfortable taking on such an intimidating role?

He was scared. He did so much preparation so that when he arrived on set he could focus. He worked with a coach, he lost 15 pounds, he went on a fructarian diet, which is the diet Steve was on when he was young.

So he took care of the nerves before he arrived on set.

He had nerves. He was calling me up at 2am. “Man, I don’t know if I’ve got it. What are we doing tomorrow?” He needed to know those things. Acting is, in my opinion, very difficult, in that, the night before a big scene, you know that by 6am tomorrow you have a big, cathartic scene where you have to break down. And, if you don’t nail that scene—if you’re not on cue, if you’re not connected, if you’re not in the moment—that scene will live in the movie forever, not fully realized. That’s a lot of pressure. I have to have the kind of relationship with the actor to where I give them space when they arrive on set to really work on getting him there. Ashton really got into the headspace before he got on set every day, and sometimes that was a rough place to be. He needed to be this guy, and this guy wasn’t always fun to be. There’s a lot of frustration in the early Mac days. He kind of carried that weight in the role. Steve in his late 30’s, when he comes back to Mac and sort of takes over again, is much more realized and so much more zen and thoughtful, and beginning to be that guy that we saw ten years after that.