Jeffrey Hatcher On ‘Mr. Holmes,’ the Tricks of Modern Mystery

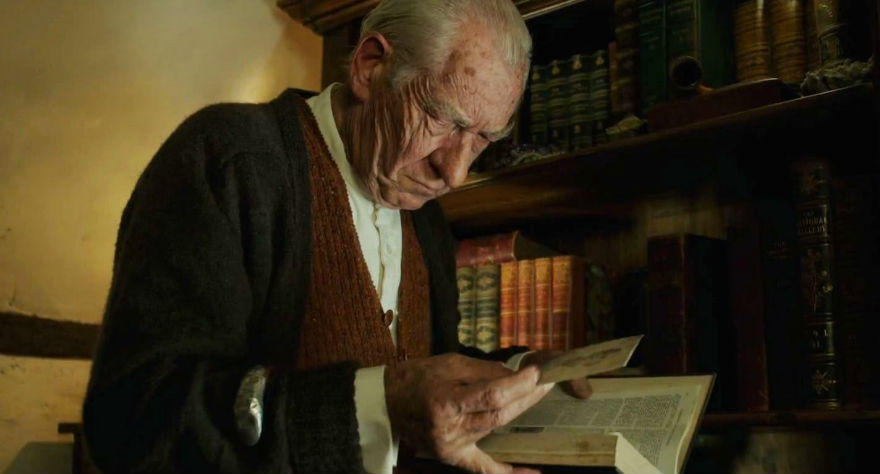

Bill Condon’s Mr. Holmes, starring Sir Ian McKellen as an aging iteration of everyone’s favorite detective, is a classic Sherlock page-turner in movie form. And rightfully so: it’s based on Mitch Cullin‘s 2005 novel, A Slight Trick of the Mind, which follows Holmes in his twilight years in a countryside home, his mind deteriorating, as he’s cared for by a housekeeper (played in the film by Laura Linney) and her son, Roger (Milo Parker). In Roger he finds a companion with whom he can share his memories before they fade away. The film also follows two parallel, flashback stories: Holmes’ trip to see the mysterious Mr. Umezaki (Hiroyuki Sanada) in Japan in search for a cure for his mental condition, and a classic Sherlock mystery involving a troubled woman reeling following two failed pregnancies.

I spoke with screenwriter Jefferey Hatcher about his experience working on Mr. Holmes, which comes out tomorrow, July 17th.

Were you on set during filming?

Yeah, for a little bit. For about two weeks at the end.

What’s it like writing the script, not being on set all that much, and then seeing the final product?

The things you focus on are the things you were on-set for. You remember, “They did this 800 times. They kept knocking that thing over.” You tend to have reference points no audience member would have. I’m always amazed with how actors can work with so much focus on them. Dozens and dozens of people watching you do something terribly intimate. I’ve done a little acting myself, but that kind of intimacy with that audience…[pauses] It’s always amazing to think how they can focus and function.

Would it be more nerve-racking for you to do something on camera as opposed to on stage?

Oh yeah, in front of a camera. It’s the same way we feel when we see ourselves in photographs. Onstage, there’s always some distance. There’s a bit of a haze.

The lights…

Yeah, right. I remember reading something Cary Grant said: “Screen acting is very difficult because I’ve got a double chin.” He’d have to keep his head a certain way or they’d see his double chin. It’s like, really? You’re thinking about this? I wouldn’t want to see myself on the screen.

So it’s the proximity.

I think so. I think actors who don’t care about that stuff, or actors who don’t care about how you perceive them and know exactly how to present themselves, do well. To have to think [like a screen actor] is kind of amazing. But the theater allows you a little more distance, even if it’s a small house.

The lights help because you can’t see faces.

No one quite gets that. I get up onstage and deliver a soliloquy to the house, and it’s like, I can’t see any of you. I can see a couple faces in the first couple of rows.

And you can hear them messing with their peanut bags.

Especially in England. The Brits, more so than us, eat during shows.

It’s more of an English thing?

Yeah. You come back from intermission during Shakespeare, and they’re eating ice cream. [In a British accent] This is the theater of the Elizabethans!

I hadn’t read the book going into the film. I was expecting more of a meditative, slower-paced movie. I was surprised to find the momentum of the film so brisk and thrilling.

The book has those parallel stories, though they’re in different sequence. That was always there. The question was, how do you shuffle it? At one point we had him going to Japan later in the script, giving it its own section of the movie. But it felt like we spent too much time just in Japan that way, so we rearranged it and made it a flashback. That was dangerous at first glance, because we had two flashbacks going on. But I think it makes sense because each story is progressing in its own direction.

The classic Holmes tale is the one with the woman in the past. Then you’ve got the domestic, current tale. Then there’s the sort of oddball tale in Japan. Holmes was going to a place where rational thinking and reason had ended up with the atom bomb going off. It comes off much more strongly in the book, but I hope it comes off in the film as well. In a sense, that’s my favorite section because it’s so controlled and tight and neat. His relationship with Mr. Umezaki is so peculiar. I’m glad the movie feels like it’s moving forward all the time and it’s not a bunch of people sitting around, talking about death.

The cast is really good. The kid, Milo Parker—he’s gotten a lot of praise.

McKellen was attached when Bill said he wanted to do it. We talked about various actresses, but very quickly, Bill said, “What about Laura Linney?” Beyond that I don’t think I had any suggestions about other actors. I adore Roger Allam, who plays the doctor. He’s got a great, soupy kind of voice. He should play Christopher Hitchens in a biopic sometime. We knew the kid had to be someone who wasn’t the classic, adorable kid. There had to be a strangeness and a quiet about him.

There’s rage in him as well.

I’d never say this to him, but he’s got, like, thyroid eyes that really pop out at you.

His glare is killer.

Oh yeah. I like the fact that you kind of have to work to get to him, which is very much like Holmes. He’s not like, “Come! Love me!” When there’s distancing like that, it makes it even better when you do embrace. Laura Linney does things I can’t even imagine. She’s so honest, never less than completely truthful. Her rage is real, her tears are real. She makes what could be an unsympathetic character very sympathetic, just by virtue of being herself. She’s a wonderful actor.

I think the three main actors are incredibly generous to each other. No one tries to steal a scene.

Sometimes there are people who say, “I’m giving you this scene,” and then they go away. None of these actors do. Their presence is so key. It’s almost as if they say, “Even if I’m off-screen, the camera’s on me.” It’s good for the film because Holmes sees people as supporting characters in his life. It’s a world of interns and secretaries and drivers, not people you actually live with. What’s cool about the film is, bit by bit, he brings them into his level, whatever that may be.

What is Holmes’ greatest fear?

He famously says to Watson in one of the stories, “I am an intellect; the rest of me is mere appendage, “which is a line we couldn’t use because it’s cut off in that copyright thing. The idea that your intellect goes away means that everything goes away. Because Holmes is suffering some form of dementia, that kind of fear of not being able to remember things or think through a problem…[pauses] It’s not simply, “I’m having some befogged days.” My essence, my soul, is being eradicated. For a man who depends, thrives, finds sustenance in that kind of intellectual pursuit, you’re really left with only two outs: commit suicide or embrace someone. The embrace is the hardest thing, because it’s not based on intellect. He had Watson and Mrs. Hudson, but they never talked about it. Here’s an example where he actually has to say to someone, “Live with me. Stay with me.”

In the post-internet age, it’s becoming harder and harder to surprise modern audiences with mystery stories. Everyone’s savvy and trying to stay five steps ahead of the plot. How do you surprise them?

It’s wildly tricky. I can’t go see a thriller where I’m not trying to out-guess it. Having the experience of having something just flow over you and be surprised [is great]. I’m probably the last person in America who was surprised by the ending of The Sixth Sense. I’m like, “He’s dead?!” It was great to be surprised. When I do out-guess something, there’s a sort of “meh” quality to it. You’re right about that. You want to play fair with the audience. There’s a bit in the movie where Holmes explains to Ann Kelmot how he knows one thing versus the other. There are quick flashes. You want the audience to say, “Yes, we saw that. The filmmakers played fair with us. But we did not expect to see the things that Holmes picked up on.” It is very tricky. The hardest thing these days is knowing the audience can go back and forth simply by moving the cursor. Have you seen The Conversation?

Yeah.

Remember the beginning? “He’d kill us if he had the chance. He’d kill us if he had the chance.” Then, when he listens to it near the end, he hears, “He’d kill us if he had the chance.” If you were watching that in 1971, you’d say, “Oh, he heard it wrong.” But now, with DVDs, you can turn it back and say, “No, she doesn’t say it that way!” They didn’t expect a world where somebody would be able to do that, technically. Now it’s harder to cheat the audience and say that something happened when they can go back and check it. If you cheat like that, the audience gets really pissed off.

You just really hope to god that, when you do the revelation, the audience goes, “Gasp!” It’s okay, actually, if some of them say, “I knew it!” Audiences sometimes like to think they’re ahead a few minutes. That’s okay. To be ahead 30 minutes is bad. But a couple of minutes isn’t such a terrible thing. Sometimes the audience wants their suspicion confirmed. You always want to present options for the audience to consider. It’s the red herring thing. If they have one option to consider, that’s what they’ll pick. So you have to give them at least two options, stated or unstated. A friend of mine says, “If the answer is either A or B, the answer should be C.”

I think being genuinely surprised is one of the rarest joys at the movies these days.

The big one here that I think we’re all so pleased with is the difference between bees and wasps. We say it right at the beginning of the film. We show you close-ups, something getting plucked out of someone’s neck. And yet, at a certain point, I hope the audience forgets that difference in the same way the characters do. To me, that’s playing fair.

In Chinatown, there’s a part where Nicholson looks into this pool, and there’s this stuff glittering. He turns to this guy, who says, “Bad for glass! Bad for glass!” Of course, it sounds like it’s a joke because he can’t pronounce grass. But he is saying glass, and he’s looking at glasses. All through the film, Nicholson is opening drawers, and there are glasses there. When he fishes out the glasses at the end and realizes they’re John Huston’s, they never say, “Oh, of course. That was a pair of glasses.” But there are these clues everywhere. The audience goes, “Aw, geez. I should have picked up on what he did.”

I think the bees/wasps thing is poetic and artistic as well. It’s not just a juke.

Something Bill put in that I hadn’t realized was how many times McKellen passes between glass. You see him in reflections and in windows. It’s all this glass within glass within glass. Some of these things aren’t things you think about, but it’s almost like you’re exercising some poetic muscle, but not intentionally. I think if you’re doing it intentionally, you can tell.

What makes Sherlock Holmes so enduring as a character? Depending on what’s going on in society in culture at any given time, we view him in a new light.

You can always tell what era Holmes stories are from. For example, Basil Rathbone, during World War II, kind of imagined that you’d need a Holmes who’s not doubting himself much, who’s going to win all the time. Nicol Williamson is a coke freak in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. It makes sense that it’s the ’70s. Jeremy Brett is this sort of crazy, near psychopath in the ’80s ones. I tend to think [he endures] because Sherlock is so anchored in the Victorian, Edwardian world. He’s so defined: we know what he looks like, what he sounds like, what he thinks. But there’s also a sadness and emptiness to him. There’s something missing in him. [Arthur] Conan Doyle will refer to it, and sometimes it’s a joke, and sometimes it’s not. But it’s always there. That’s the crack actors, writers and directors get to fill.