Alex Garland On ‘Ex Machina’, Oscar Isaac, the Fate of the ‘Dredd’ Sequel

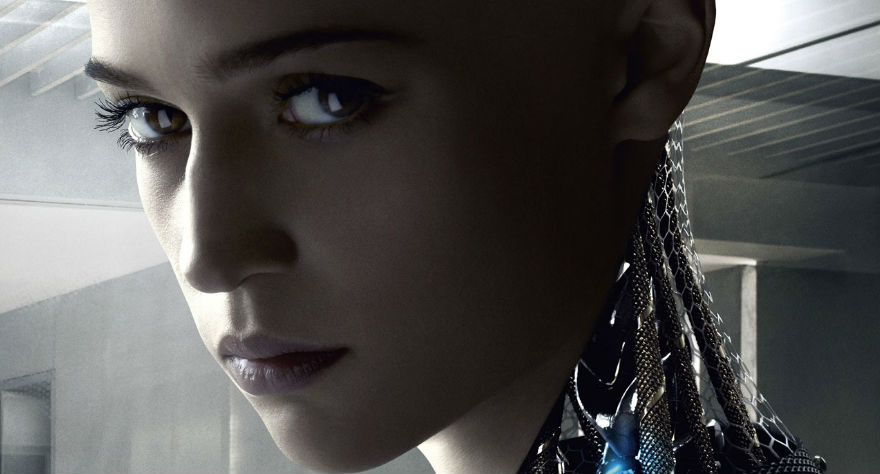

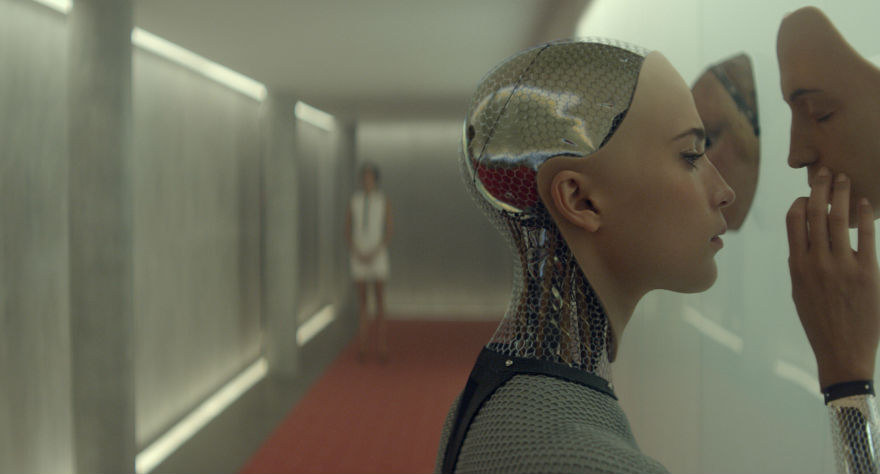

Alex Garland, a novelist-turned-cinematographer, has written some of the most geeked-about movies of the past 15 years: Sunshine, The Beach, 28 Days Later, and even a terrific video game called Enslaved: Odyssey to the West (if you haven’t played it…play it). Now, with Ex Machina, Garland is making his directorial debut, and it’s an indie sci-fi doozy. The film follows Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a young coder at the world’s largest tech company who’s invited by his boss, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), to participate in the grandest experiment in human history, involving a robotic girl named Ava (Alicia Vikander), the world’s first sentient AI. Mysterious, smart, and full of surprises, Ex Machina is about as awesome a feature debut a director could have, and we had the privilege of speaking with Mr. Garland in a roundtable interview during his visit to San Francisco to promote the film.

Ex Machina is playing now in New York and Los Angeles, opens tomorrow in San Francisco, and expands wide next Friday, April 24th.

What’s sexy about the uncanny valley to you?

You inadvertently flatter me with that question. The uncanny valley in this movie is, for me, something that is exhibited within Ava specifically in her movements. The way Ava moves is not robotic; it’s like a too-perfect version of how humans move. And in the perfection of those movements it feels a bit “other”. It’s quite hard to say why. I just feels a bit off, a bit “other.” The reason I’m saying you’re inadvertently flattering me is that, that had nothing to do with me at all. It was something Alicia Vikander arrived with. She was a ballerina since age 11 and she’s got incredible control of her physicality. The uncanny valley was brought here by Alicia as a way to approach playing this robot, and as soon as she said it I thought, “This is absolutely brilliant.

I’m trying to have a conversation, partly, about where gender resides. Is it in a mind, or is it in a physical form? Is there such a thing as a male or female consciousness, or is that a meaningless distinction? Maybe the gender resides in the external, physical form, or maybe in neither. There’s a broader question about what you call this creature: Do you say “he”, “she”, or “it”? It would be quite easy to present an argument saying Ava has no gender. That said, calling her “he” just feels wrong, with the way she looks. To use the word “it” feels disrespectful. You end up with “she”, and you end up with the strange thing of, is she a ‘she’? And just to be clear, of the questions that are posed in the film, some of them don’t have answers. But that doesn’t mean posing the question is wrong.

When it comes to sexuality, there’s a different thing going on there. Essentially, it’s about the fetishization of girls in their early twenties. Now, that’s not about gender; it’s a completely separate issue. I know there appears to be a Blue Beard narrative and a savior narrative in the film, but basically what you have is both a seeming protagonist and an audience being tasked with something, which is, “Tell us what is going on inside the mind of this being. Is it thinking?” Then, obstacles are presented to both the protagonist and the audience, which effectively get in the way of the question, “What is Ava thinking?” In the end, the thing the characters fail to do is establish what she’s actually thinking, and that allows her to trick them.

I think people are a little anxious and fearful of artificial intelligence, but you actually think it’s a good thing, perhaps even an improvement on human beings.

I do, and I also think that a lot of the stuff that’s perceived to be anxiety about artificial intelligence has actually got fuck-all to do with AI. There are two separate things going on: You’ve got Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk saying artificial intelligence is potentially really dangerous, being possibly anti-AI. And I’m talking about strong AI, not video games and mobile phones. That’s potentially true and potentially reasonable, but you could say the same thing about nuclear power. It’s potentially dangerous, and that doesn’t necessarily stop us from using it. The question is [about] how it’s used. With humans, it tends to be the case that, when something’s possible, we then do it.

The question to ask is not, “Should we do it or shouldn’t we do it?”, because we’re going to do it no matter what if it’s possible. The question is, “How are we going to deal with it when it happens?” That aside, I think a lot of the anxiety doesn’t actually come from AI. There have been a lot of stories about AI in film lately, from Transcendence, to my film, to Age of Ultron. There are tons of them that suggest this zeitgeist in the air. Why is that? Has there been any real breakthrough in AI? Not really. I think it’s probably got nothing to do with AI. I think it’s to do with tech companies. It’s because of our laptops and our phones. We don’t really understand these things, but they know a lot about us. So what you get is a sense of anxiety, either consciously or unconsciously. I think these AI stories are a consequence of that anxiety rather than anything specifically to do with AI.

There are a lot of little things Oscar does with his face that convey a lot to the viewer without giving anything away. Was that a conscious decision on your part?

People say a director got a performance out of an actor. I didn’t get any performances out of any actors. This is something Oscar brought because he’s an incredibly gifted actor. What I think you seek from an actor is that they will elevate everything to do with their character and find things that you never even thought of, improvements and stuff like that. That’s true of the DP, the production designer, the brilliant composers…and true of Oscar.

Does that suggest that you give your actors free rein on-set, or do you like to have some sort of collaboration?

The way I see it, I perceive myself as being a writer, primarily. I write the script and present it as a blueprint to people. Then, I’m not looking to control anybody. It’s almost like what you’d ideally want anarchy to be: a group of people, quite autonomous but also collaborative, working together with a shared goal. That’s my approach to filmmaking, broadly. I don’t like auteur theory. I find it boring and misleading and inaccurate a lot of the time. It’s definitely not what I am. I’m part of a team, and I like that. Years ago I used to work on books. You sit in a room, and you write a book. That’s “auteur.” There is no real comparison to working on a film with a lot of other people. Actually, the thing I dig about film is that it’s collaborative. That’s the pleasure in it.

Can you tell me more about the relationship between Oscar and Domhnall’s characters?

There are two things going on there. One is, [Nathan] is deliberately winding this guy up, presenting himself as something from which this machine needs to be rescued. He’s presenting himself as a bullying, misogynistic, predatory, violent man so this kid can rescue the machine from him. Now, there’s a question: Is that a complete confection? Is that just an act he’s doing? Or is he amplifying something that’s within his own character? That’s one of the hovering questions going on in the story. There’s another thing he’s doing, the “dude, bro” stuff. For me, it’s slightly trying to represent the way some tech companies try to represent themselves. It’s kind of like going, “Hey dude, hey bro, we’re pals! We’re a bunch of hipsters listening to music! By the way, can you give me all of your money and all your information? Thanks, dude!” That kind of speak cracked me up a bit.

So Domhnall’s character is administering a Turing Test…

Sort of. It’s pedantic, but it’s sort of a post-Turing Test. It’s a blind test. A Turing Test is really a test to see if you can pass the Turing Test. You can pass the Turing Test and not be sentient. What he’s saying is, this machine would pass the traditional form of the Turing Test; I want to know if I can show you it’s a machine, and you still think it’s sentient. It’s a step up.

There’s a kind of Turing Test going on between your team and the audience. You’re trying to convince the audience, through Alicia’s movements and visual effects, that she’s a synthetic thing walking around on-screen.

Initially. And hopefully, people are forgetting that.

Most of the legwork for the illusion is done by Alicia, but the visual effects are pretty incredibly. They had me stumped.

The effects are really brilliant, and they were run by this guy called Andrew Whitehurst, with a big team under him. I’ve met some really smart people in my life, [but with Andrew,] I did sometimes think, “You are literally the smartest guy I’ve ever met.” He has enormous creative instincts. I remember him saying early on, “I want to hang these plastic strips inside her torso that will diffuse light and make these structures inside her look slightly more mysterious.” It was a really subtle, nuanced idea that was very typical of him. Very late in post-production, there was a problem to do with the way the camera rendered pixels. It was going to cause us a huge problem, and he said, “I’ll fix this.” He wrote a bit of code that basically reworked the pixels and fixed it, and it fucking blows my mind that he’s able to do these things.

Can you comment on any movement for a Dredd sequel?

Not really. Not because it’s one of those coy things, like I’m demurely going to say “no.” It’s because there isn’t, as far as I can tell, going to be a Dredd sequel. The basic mechanics of film financing say, “If you make a film that loses a ton of money, you’re not going to get a sequel,” and that’s basically what happened. I understand and appreciate the support the film has had, the campaigns that have existed for it, and it’s extremely, genuinely gratifying. I love it in all respects except one, which is when I hear about people buying copies of the DVD in order to boost sales and change the figures. What I want to say to them is this: Don’t do that. Keep your money. The people who are making the decision are much colder and harder than that. The graphs they’re looking at aren’t going to be sufficiently dented by it. The support for the film is truly appreciated, but if there is going to be a sequel, it’s not going to be from me and the team who worked on the previous film. It’s going to be another bunch of people, and good luck to them. I hope it happens, and I hope they do a better job than we did.