Hossein Amini: I Struggle So Much With Dialogue…I Find Silent Storytelling More Interesting

Best known for writing Nicholas Winding Refn’s Drive, Hossein Amini makes his directorial debut with the ’60s noir-ish throwback, The Two Faces of January, based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith. Set in Greece in 1962, the film follows a vacationing American couple, Chester (Viggo Mortensen) and his wife Colette (Kirsten Dunst), who get intwined with a small-time conman named Rydal (Oscar Isaac) when he witnesses Chester committing a deadly crime at their hotel. Rydal offers to help the couple flee to Athens, and as the three evade the authorities on the streets, Chester is forced to compete with the younger Rydal for his wife’s affections.

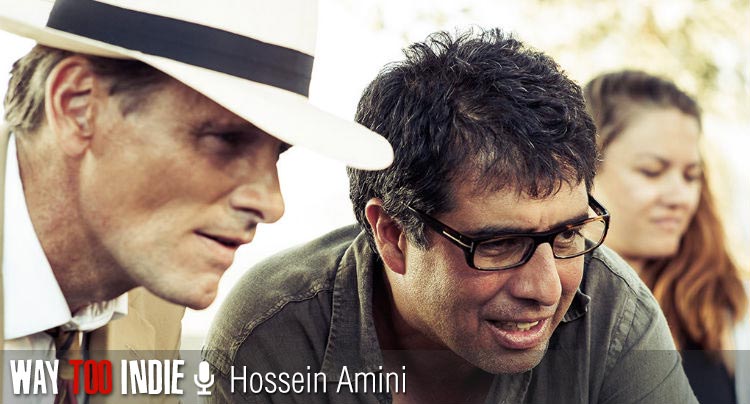

In media roundtable interview conducted at this year’s San Francisco International Film Festival, we spoke to Hossein about the film’s ’60s influences, his attraction to weakness in characters, Highsmith’s fascination with male competition, silent storytelling, the film’s period set and costume design, and more.

The Two Faces of January is out this Friday in San Francisco.

Your film resembles a lot of suspense noirs from the ’60s. What were some of your inspirations?

Hossein: I’m a total film nut, and I love film noir, so I couldn’t wait to get to Turkey to shoot that. I wanted to, in a way, recreate that period of [’60s cinema]. It was important to not be too contemporary with the camera moves. It was such a novel period in filmmaking, with the French New Wave and Italian cinema. I watched a lot of European movies from that time. But I always go back to ’40s and ’50s American film noir, because that was my first real movie passion. I remember seeing Kiss Me Deadly on the big screen, and it blew me away. It was the first time I fell in love with movies. Hitchcock is an influence as well. The French talk about a “film soleil” as opposed to a film noir, which is a film noir shot in the sunshine. I kind of love it. It’s that idea of oppressive heat and dust in these landscapes.

Did you feel that the more rugged landscapes revealed the real nature of the characters?

Hossein: That was absolutely the intention. We wanted to start off [Viggo] with this beautiful suit, and [Kirsten] with this dress, and gradually, as those layers are stripped off, it starts to reveal who they are. I remember liking those characters as I read the book. They’re so fragile, and I think it’s rare when you get movie characters who are weak. We make films about bad people or villains, but I think villains that are actually human are rare. I know how difficult that is; we did test screenings and the audience said, “I don’t have anyone to root for.”

I have to accept that, but I think that’s what makes [Patricia] such a great writer. She just strips these characters naked. She’s kind of cruel and compassionate to them as a writer, and that’s something I capture in the movie. I like Chester. I don’t know what other people think, but he was the character when I read the book that really made me want to do this. I felt he was jealous and drunk–all these weak human qualities–and yet there are sometimes moments of dignity.

Talk about the challenge of being an homage to those films without becoming “retro”.

Hossein: It is a fine line. Some people do find it goes too far into the Hitchcock pastiche, which wasn’t intentional. The characters are so modern; that would be my defense of what makes it contemporary. [Patricia] was so ahead of her time in that her characters change so quickly from being kind to cruel, from vicious to suddenly having remorse. It doesn’t happen in scenes; it happens almost within moments. One example is when they’re all sitting around at dinner and there’s dancing going on. Rydal is flirting with Colette, and then he remembers her husband is there, and he’s almost apologetic. That’s something about her writing that I found…it’s almost how I behave. That doesn’t say particularly good things about me, but I can suddenly be mean to my wife and feel terrible about it the very next moment. She captures this very modern psychology.

There’s a big father-son theme in the film.

Hossein: When I read the book I thought, what does The Two Faces of January mean? One is the idea of the god, Janus, that has got the two heads facing outwards. I thought it was interesting, because no matter how much [Chester and Rydal] hate each other, they’re twins, and they’re tied together. Also, it’s about the new replacing the old. Back in early times, the son would have to kill the father in order to become a man. There’s something about the sense of competition and admiration going together between a younger man and an older man. Highsmith is so fascinated with the relationships between men. I think she’s much more interested in that. In Ripley, she gets rid of Marge fairly quickly. The father-son thing is a way for her to show a love story and a hate story between men.

A lot of the storytelling in your film is told through the actors’ eyes. Some of the most significant scenes are silent.

Hossein: As a screenwriter, I’ve always felt the dialogue is there to set up those silences. It’s about the space between the lines. If you have a scene where a woman is on the phone with her lover, and then she goes to her husband and talks about the weather, it can be the most moving, powerful scene. The dialogue is irrelevant, really; it’s the subtext and the looks between them. In marriage scenes, the couple rarely talks about the problem, but the undercurrent is always there. I think that’s what I love about movies–the close-ups, the silences, the way you feel people’s pain. Quite often, we’d cut to who’s not talking in those three-way conversations, because I think that’s where the drama is.

I struggle so much with dialogue as a writer. I find it very hard to write. If I could write like Tarantino, I’m sure I’d be huge! [laughs] I find silent storytelling more interesting than people saying what they actually think.

Are you angling for a silent picture next?

Hossein: One of my favorite directors, [Jean-Pierre] Melville, who did Le Samorai and Le Cercle Rouge…there’s almost no dialogue in those.

Colette sort of fades into the background about halfway through the film. How does this compare to the book?

Hossein: The book has that thing of her disappearing from the picture. That was always there. When I wrote the script, I thought I needed to make it more of a triangle, and we shot it like that. In the book, it isn’t; Highsmith isn’t that interested in her. When I was editing with the editor, and when we test screened it, we found that Highsmith’s DNA came back to reclaim [the film]. People were more interested in the relationship between the men, the same way as an author she had been. We felt after a while that going back to the book and making her the catalyst and object of competition for the men [is better]. Kirsten resists that kind of thing, but I do think that her part was a struggle than the movie. She was better than the part, I think, and we both struggled to make that part better. But in the editing, the shape of the movie pushed it to her being watched as opposed to being in the center.

Talk a bit about the set and costume design. That must have been a fun experience to watch that come together.

Hossein: As a writer, my favorite thing about writing a script is the research. We went through a lot of ’60s photographs, which you can find on the web. It’s amazing, just home photos of people from that period. Then there are the movies from that period, like Alain Delon wearing a white suit. What I liked about directing for the first time was that everyone knows what they do so much better than you do, and it’s fantastic to watch how good other people are. If you let them, people really want to help you. I wonder if that happens on the second or third film, because maybe people step back. But here, being open to that was really helpful.