Gabriel Mascaro on Breaking Stereotypes and Empowering Characters in ‘Neon Bull’

In Neon Bull, writer/director Gabriel Mascaro takes viewers to a familiar yet strange world in northeastern Brazil. The film hones in on the Vaquejada rodeo, an event in the area where cowboys drag a bull to the ground by grabbing its tail. It’s a popular event throughout the region, and one Mascaro has a familiarity with. “I come from Recife, and at the school I studied at as a teenager there was a lot of influence about Vaquejada,” he explains, before talking about attending a Vaquejada party when he was 15 years old. “I never thought that, 15 years later, I would be making a movie about them.”

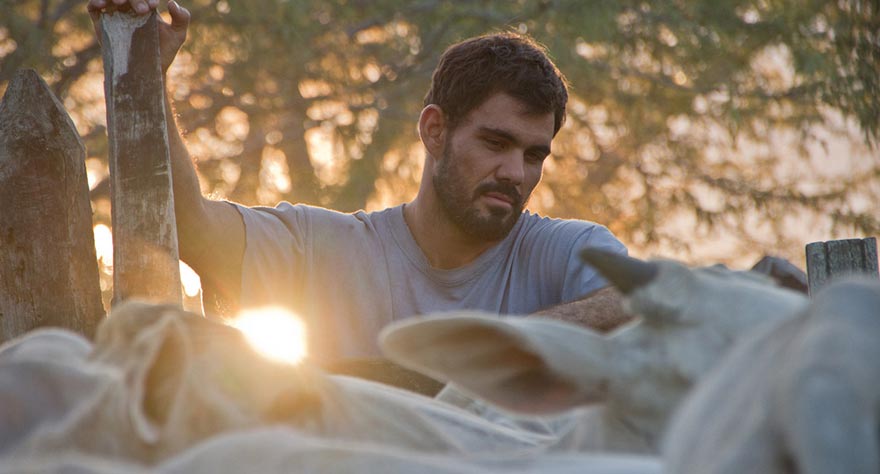

But Neon Bull doesn’t keep its focus on the rodeo events themselves, although the performance sequences provide some of the film’s best moments. Mascaro focuses on a small group of Vaquieros, people who work behind the scenes transporting bulls to each stop on the rodeo’s tour and making sure each event goes off without a hitch. The group’s makeshift leader is Iremar (Juliano Cazarré), the main Vaquiero who’s a pro at his job, and Mascaro observes Iremar and his coworkers as they deal with their daily existence both at work and within their surrounding environment.

Beyond his personal connection, Mascaro’s interest in making a film about the Vaquejada rodeo had to do with the link between the film’s subject matter and location. “When I started thinking about Vaquejadas as an environment to translate into a movie, I had the opportunity to meet a cattle rancher that also worked part-time in the textile industry,” Mascaro recalls, a piece of information he eventually used as the basis for Iremar’s character. The textile industry’s success in the region is one thing Mascaro cites as evidence of significant changes happening in his country. “Vaquejadas work as the scenery for a lot of the transformations that Brazil has been having for the last ten years, a lot of social and economic transformations.” And while the film is never explicit in laying out the political and economic changes going on in the background, it dominates what goes on in a film Mascaro describes as being about “a body in a transformational environment.”

That idea of transformation also applies to transforming preconceptions about gender norms. “The movie is very interested in the concept of a body,” Mascaro says. “It’s not fixed to a specific gender.” Neon Bull repeatedly finds ways to subvert the sorts of expectations one might make when watching a film about such an aggressive and masculine setting. Iremar is a strong, hulking presence when working as a Vaquiero but in his downtime, he pursues his dream of becoming a fashion designer, sewing clothes in a nearby textile factory. And partway through the film, Mascaro brings in a new character named Junior (Vinicius de Oliveira), whose slim body and long hair stand out when compared to the muscular rodeo workers around him.

Mascaro believes that, in order to break stereotypes involving masculinity and gender roles, the camera’s placement needs to be taken into account. “One of the central issues for me in regards to moviemaking is the relationship between the distance of the camera to the object being filmed. If the camera is too close, it might reinforce too much of a stereotype. If it’s far away, it might break the stereotype. You empower much more if you’re far away, with a full frame of the body. So I tried to translate this into a dance or choreography of the body into this transformational environment.”

The film does largely unfold through long, uninterrupted takes filmed with the camera at a distance, a choice that also gives Neon Bull a naturalistic, almost documentary-like appearance. Mascaro, who has a background in documentary filmmaking, and cinematographer Diego Garcia (who also worked as DoP on Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendour) use their style to help normalize some of the film’s more surreal or provocative moments, whether they’re aesthetic (the neon-drenched rodeo sequences) or explicit (a graphic sex scene between Iremar and a pregnant woman). This is a deliberate choice on Mascaro’s part, explaining that “even surrealism is within the context of a spectacle, a show, and that’s how it becomes naturalism.”

The other big contributor to the film’s natural mood comes from the cast, an ensemble made up of professional and non-professional actors. “We worked with Fatima Toledo, who did actor preparation for City of God as well, to break barriers between formal actors and non-actors and bring them to a common level so there’s no tension.” A lack of tension seems important for a film shoot like this, given the lengthy and well-choreographed sequences throughout. Mascaro says there was “a lot of work involved,” especially with sequences like Iremar urinating in front of the camera, a shot that took eight hours to complete in order to achieve the correct camera movement, along with Cazarré being required to piss on cue. But the biggest challenge was a scene where Cazarré had to masturbate a horse, a situation that Mascaro laughs about today. “[Cazarré] said ‘No way, you’re pushing the limits, I’m not gonna do this unless you do it first.’ So I did.”

This interview was conducted in September 2015 during the Toronto International Film Festival. Special thanks to translator Daniel Galvao.