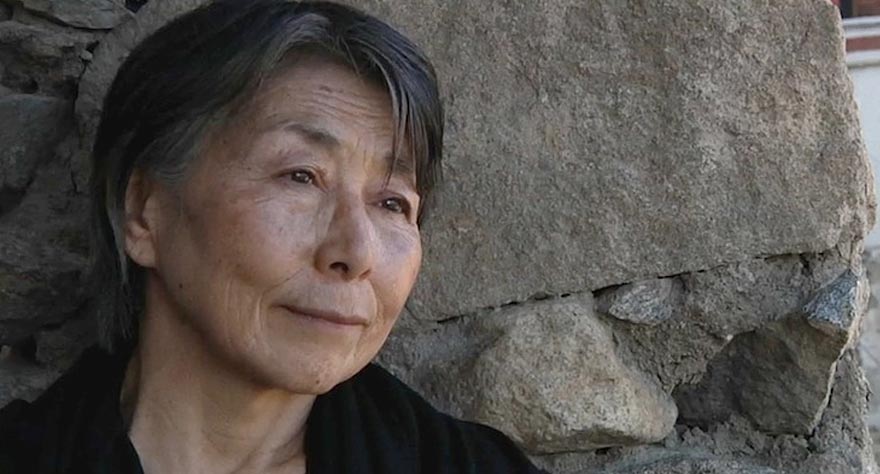

Documentarians Daniel Traub & Glenn Holsten Travel the World with ‘The Barefoot Artist’ Lily Yeh

Artist Lily Yeh is based in Philadelphia but has extended her community-based art projects to many of the world’s most conflicted locations. Through her beautification efforts, Lily has revitalized a Northern Philadelphia community, brought relief in the form of a memorial in a genocide survivors’ village in Rwanda, and many other artistic ventures in the pursuit of healing people. Since the mid-1980’s, filmmaker Glenn Holsten has chronicled several of Lily’s projects, and more recently, Lily’s own son Daniel Traub has lent his filmmaking abilities to chronicling of Lily Yeh’s work.

In the years since, the documentarians have teamed up to produce The Barefoot Artist a film on the life of Lily Yeh and the good she brings to communities through her art. Many years in the making, The Barefoot Artist is playing now at the IFC Center in New York City, and will open in Los Angeles’ Laemmle NoHo7 on December 18th. I spoke with the co-directors by phone about their new movie.

I wanted to start with the pretty obvious question or Daniel, because aside from being the co-director, you’re also Lily’s son. So how long has this documentary been gestating?

Daniel Traub: I actually hadn’t intended to make a feature length film. I had been living in China and I came back to the States in 2008, and my mother at the time was doing projects all over the world. A lot of her projects are short lived, and don’t really last for that long, so in a way her work lives in one form through the documentation. So she kind of asked me if I’d be interested in going with her to some of these places and it was hard to refuse to go to some of these places like Rwanda, China, places she was working.

Initially I was making shorter pieces just for her own documentation, but as I got more involved with it then I began to see it as a larger film. That there was the possibility of making a more ambitious piece, so it really happened more organically without my having an initial idea of making this film.

So Glenn, what then first drew you into Lily’s story?

Glenn Holsten: I’ve known Lily for… someone said 30 years which is kind of frightening, but it’s been a long time. Since the late ‘80s. I worked in public television in Philadelphia for many years and she was starting a village in North Philadelphia. So all that footage that you see of the village getting started was projects that I worked on, and I slowly became intwined with the village for a while. I taught there, took classes with young children, and I stayed in contact with Lily throughout my career, and when she went to Africa I said, “Can I go with you?” And then she was going to China to meet her family, and I said, “Can I go with you?” And she said, “Yeah.”

So all along I was making different projects with Lily and it started culminating in this story about her family, the two sides of her family getting together. That we filmed in China and Daniel was living in China at the time, so that’s how we came together to tell that part of the story. And then as we started to edit that footage together I started to realize I was missing a big part of her life, which is her creative side, her art work. Daniel had done some amazing documentation of that, so that’s when we decided to come together and make a movie about the two sides of her life.

What she has always said is they’re two parts of the same journey. So we had sort of had that as an inspiration.

So the entry point then for the both of you was this trip to reunite her family.

Glenn: I would say yeah, Daniel don’t you think that started off the movie?

Daniel: Yeah. Yeah, that’s right.

Glenn: And it was great because I knew Daniel from life in Philadelphia… it made production very, very possible and very interesting.

How long have you two been working together to make this film?

Daniel: That initial journey was in 2005, so I guess that makes it 10 years. It’s been over starting and stopping, and not one consecutive time period.

Glenn: This is a passion project, not a rent project, so you make it work.

How much of the project then was newly created footage, aside from that trip, or was it all just mining through the years of her work and pulling together a narrative from that?

Glenn: That’s a great question. I mean, I have to think in percentages I’d say it’s probably 50 / 50. We did some shooting afterwards. We did some more focused shooting in the end. In the big white interview, we call it the white interview where she’s sort of telling her story. What do you think Daniel? Do you think 50 / 50 or 60 / 40?

Daniel: Yeah, 50 / 50 is about right.

You have all this great archival footage, but as you mentioned Glenn you filmed a lot of it and Daniel you had as well. With that knowledge base, are you going through things you remember having worked on with Lily, or do you have to dig through the old material that you’ve amassed when pulling together that archive stuff?

Glenn: We dug through the old stuff, and reminded ourselves. There are some moments that I always remembered, but there are some things are there that we found that are absolute gems. There’s a couple of overhead shots that I didn’t remember shooting at all in North Philadelphia that showed the landscape really well. Even the quality of the tape, it was on beta, beta tape. So even the quality of the tape looks like another life ago. So it was funny going through all the old stuff, we enjoyed it.

The film begins with a statement about beauty’s relationship to destruction that serves as close to a thesis statement as you’re going to get for Lily’s work. How early on did you know that that would be an effective encapsulation of your film?

Daniel: I think that’s something that my mom, Lily often says. So I think it sort of stuck in all of our minds. We tried several different beginnings, and I think we had something early on, it may have included that or not, but in a way we went through the editing of the whole film and then that sort of emerged again to be a key phrase. Then I think we put it back there. On some level we started at that then went through the process and reaffirmed that that was the key phrase in the film.

Glenn: Yeah, you’re right, we had that at the top of the very first cut and then we strayed from it. We doubted ourselves. We shared it with a bunch of audiences and felt like we didn’t attack it fully as we had in the past so we reworked the top to include that, and then that footage of her drawing that black line on the white paper.

You spend a large chunk of the film in this genocide survivor’s village in Rwanda, Daniel was that something you filmed on your own?

Daniel: Yeah, it was on my own.

What was that experience like?

Daniel: I had gone about three times to Rwanda. The first time I went I was actually working on another project in Uganda, near by, and my mother was working in Rwanda at the time so I was right next door. I just crossed the border and spent about a week there, not filming just spending time and learning about the genocide and the project. And then later, I think about a year later, my mom went back and I decided to go back with her to film, so I already had some background.

It took me some just sort of learning and familiarizing myself with the situation until I felt able and prepared to go there and film. It was very powerful and moving. I became pretty close to some of the people that I filmed and it was just a very powerful experience. I think filming in a way it’s helpful, because there’s a little bit of a shield; you’re shielded from what’s happening in front of you to some extent. That made it easier a bit easier to be working.

Daniel, you have a small role in the film. Was there ever a debate about whether or not to include yourself, or perhaps include yourself to a larger extent?

Daniel: Yeah, that was one of the debates that we struggled with. Glenn and I and the editor. I didn’t want it to be my story, I thought the film really should be about my mother. I thought that to have me more in the film, then it becomes more of my story and I didn’t really want that. I think that we kind of settled on a degree to which I’m involved that I think we all felt comfortable with. That I think works well.

And I think if I were more in the story, in a way it becomes too complicated. Different story strands. I mean, we tried it in different edits, I think we all agreed that it became a little bit overwhelming and too convoluted.

Glenn: Yeah, Daniel had written some narration bits and there was also a scene in India where they have a conversation about their relationship. We did try them all but it felt like it pushed it into that zone that Daniel’s describing, where you weren’t sure where to focus. We streamlined it a bit.

I think the film does a really admirable job of challenging critics of beautification projects, that label those projects as misplacement of resources, I was curious if either of you had any thoughts on that.

Daniel: Well one thing is it’s not only a beautification project. In Rwanda, she is engaging the people in different projects to help them make a living, help them in education projects, water purification so, I would say that the beautification is just one part of it. But even if it didn’t, I feel that it’s extremely valuable. Particularly in Rwanda, building a memorial is something they needed on a very fundamental and emotional level, so I would refute any critics.

Glenn: North Philadelphia’s been the same, it started out as a park, but now it’s an after school center, it’s a business incubator; it’s an employer of residents of that neighborhood. And many of the people who have worked there I’ve known for years and years and years, so it’s been a staple of that community. It’s really grounded a lot of lives there so it does start with art, for sure, but it’s always been part of her design to move through it. Keep art always there, and view everything in an artistic lens, but business and development are definitely a priority as well.

What do you hope audiences take away from the documentary?

Daniel: A lot of what I’ve heard from audiences is that it triggers a lot of things that resonate in their own lives. There’s some family issues, and a sense of being able to kind of go into their own stories and have the courage to go look at them and explore them. That there is a way to resolve them. So I think that’s one aspect.

And I think what my mom has done with her life is also very encouraging, and it brings people a lot of hope, so I think that’s another aspect.

Glenn: I know what I take from the story is this crazy, braveness that Lily has where she just starts. She doesn’t start with an overall plan, she doesn’t say, “I’m going to change this neighbor,” “I’m going to build this memorial,” she says, “I’m going to start with this person right now,” and her method is with art. “I’m going to start making art and we’ll connect that way.”

So I hope that people feel empowered to start addressing things that they want to be a part of, whether it’s just a family issues – she faces a very difficult family situation head-on, she goes and brings the two families together. She’s an agent of change. So I think we all have the potential, and she’s a human being too, so she has flaws and frailties but she’s also a pretty crazy, brave woman. But I hope that people that in their own selves, just a little bit of that spark.

Are either of you at work on other specific projects now?

Glenn: Yeah, Daniel’s got a great book out, of his photographs of North Philadelphia. He’s a fine art photographer as well as a director of photography. And he and I have been working on a film about a mental health recovery community in Philadelphia that has a beauty parlor that’s part of a therapy program there. It’s called the Hollywood Beauty Salon, and it’s about the lives of these members of the beauty salon that’s part of a recovery community. That will hopefully be out in the world in the Spring.