Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Talk ‘The Galapagos Affair’

In The Galapagos Affair: Satan Came to Eden, married San Francisco filmmakers Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller explore the dark human history of the titular islands. Filled with deceit, jealousy, and murder, the island lore has all the trappings of a juicy whodunnit, and the film is being aptly billed as “Hitchcock meets Darwin”.

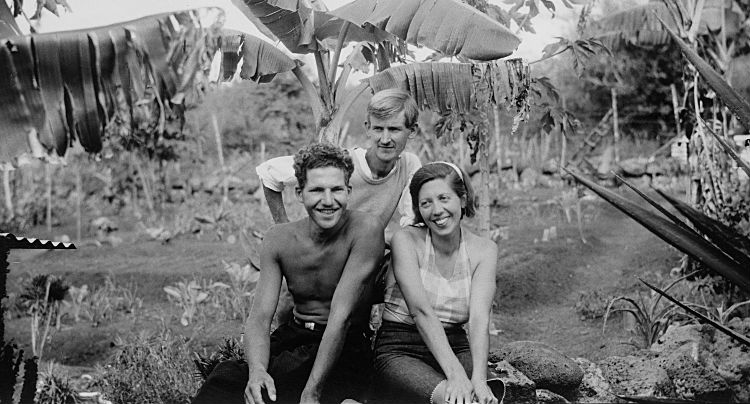

The film centers on German settlers Dr. Fredrich Ritter and his lover Dore Strauch, who escaped to the uninhabited island of Floreana to build their own private paradise. They weren’t alone for long however, as the Wittmer family and an Austrian Baroness soon barged into Eden, marking the beginning of a cramped, combustible situation that ended in death.Mixing unbelievable archival footage of the European ex-pats (narrated by Cate Blanchett, Diane Kruger, Josh Radnor, and more) who settled there in the 1930s with interviews with their descendants and present-day settlers on the islands, the film weaves an almost fantastical murder tale while keeping itself grounded in real emotion.

Goldfine and Geller spoke with us in San Francisco about discovering the Galapagos mystery for the first time, finding the incredible archival footage of the settlers, why they incorporated modern footage into the film, the film’s strange musical score, and more.

What was it like stepping foot on the Galapagos Islands for the first time in 1998?

Dayna: Oh god. I wasn’t prepared for how emotionally moving those islands were going to be. You read about them, about Darwin…philosophically, in a theoretical way, they’re out there. But to actually go to those islands, be with those animals…It was one of those “ah-ha” moments like, “Yeah, I kind of understand Darwin now. This is how it all began.” Geologically, they’re quite young as far as islands go. In terms of the important history that’s happened because of them, it’s very profound, and you feel it as soon as you set foot on one of the islands.

Dan: I remember thinking, “How on earth could anyone really carve out an existence here?” It’s so rough. Beyond being isolated from the rest of civilization, it’s not an easy place to be. When we first set foot on the islands, I had no idea of this murder mystery, but I remember thinking, “Why would you want to come here?” I knew the lore of the buccaneers and the pirates and all that. They were whaling, and it made sense as a temporary stop. But to set up a life there, to me, was an astounding leap to make.

Dayna: I have a hard time thinking about even leaving San Francisco, because we’ve spent decades here and we have a very rich friendship circle. For me, what these people did, saying goodbye to family and friends and thinking you’d probably never see them again, was such an anathema. I couldn’t wrap my head around it.

You originally visited Galapagos for a different project, correct?

Dan: Yes. We were there as cinematographer and sound person, shooting footage for an interactive educational project for our friend Doug. We were there without any notion of the human history of the islands. That wasn’t part of his scope for the project. We were quite surprised to begin to realize that there were inhabitants in Galapagos, though not indigenous. That was surprise number one.

Dayna: It took a couple days of being on the boat and seeing this book, which was about the human history of the islands, to wrap my mind around that.

Dan: And then that fateful chapter you read…

Dayna: (laughs) Yeah. The fourth chapter was called “Murder in Paradise”. In these little twelve pages, it was everything you could imagine in a Hollywood fiction film. As I was reading it, I had to keep reminding myself that these were real people and this really happened. If half of this stuff really happened…What an incredible story!

What was it like meeting Margaret?

Dan: We weren’t supposed to be on Floreana at all. The itinerary for the trip we were taking had us going to other islands. You don’t willy-nilly stop off at an island in Galapagos. The National Park controls the itinerary of the boats very specifically. Dayna had read this chapter, and we knew that Margaret Wittmer was the last to stay alive on this whole adventure. Dayna kept saying, “Can’t we stop at Floreana?” the whole trip. Every day. Finally, the boat broke down, and the nearest island was Floreana. That’s how we wound up going there. Our park guide Miguel had known Margaret for many years and said, “Off limits. Do not ask her about this. She doesn’t like to talk about this.” We were unexpected guests, but we sat with her and had tea and cookies, of course wondering whether they were poisoned or not! (laughs)

Dayna: No we did not! (laughs) It was a joke! At the time, neither of us spoke Spanish. Even though her primary language was German, because these islands are owned by Ecuador, by the time we met her she spoke fluent Spanish. She said, “En la boca cerrada no entran moscas”. Miguel started laughing, but we didn’t know what it meant. He told us, and we were like, “Oh my god!”

(The English translation is “In a closed mouth, no flies will enter.”)

Dan: Nothing we were talking about with her would have made that comment make sense, except in hindsight. She had a little bit of a reputation for playing with the notoriety and the myth. You couldn’t ask her about it, but then she would do something sly like that. She had a sly sense of humor. She was toying with us.

The seeds were planted for this project in 1998. It’s been a long process. Talk about the watershed moment when you discovered that footage of the inhabitants in the book existed.

Dayna: The first inkling was when Doug called and said, “You know that story you were completely gaga over a couple years ago? This professor at USC told me about this little stash of footage.” Could this be real? We looked at this VHS tape that had five minutes of the footage that had been transferred, and we were like, “Oh my god! That’s what they looked like! They existed!” Then we thought maybe we could actually make this movie.

So that sort of sent you on your way.

Dan: Definitely. That and knowing that Margaret had written a memoir, Dore had written a memoir, and we found John Garth, who visited every year, kept a journal. Then there were the newspaper and magazine articles that Dr. Ritter and others wrote. Now we have all of these first-person accounts, Roshomon style. What if we made this film all from their point of view? They’re the unreliable narrators. It makes for a more intriguing whodunnit, I think. You can view the footage through their eyes. You can start hearing Dore say something about the Baroness, and while the same shot is continuing to play out, get Margaret’s take on it. Then the Baroness herself. It allows you to keep reinterpreting that footage. Who’s telling the truth here?

Dayna: After we finished working on our Ballets Russes film, we got back in touch with the USC professor who knew about the footage. We went down and looked at this room filled with disintegrating 16mm reels. It smelled like vinegar.

Dan: It’s called “vinegar syndrome” when the acetate devolves under its own age.

Dayna: We thought, we’d better get this footage transferred as soon as possible. It was clear that not all of it was going to be salvageable. There were reels that were just solid, glued-together blocks. We took as much as we could.

So you have this mountain of material to cull from. But now you introduce footage these modern subjects into the film, who live in Galapagos now. What was the thinking behind including them in the story?

Dan: These are people who similarly decided to leave civilization behind and move to Galapagos and therefore could speak about their psychology, emotion, and fear as well as about the murder mystery itself. There are people who were born to those parents, in 1940 or 1950, who grew up in what was supposedly paradise for their parents. We were curious: What is it like not just to leave civilization and go to a place like this, but to be born in a place like this? Is it paradise for a child? Do you hunger for civilization? It’s the backwards story in a way, and I think this and the archival element inform each other in a way.

Dayna: It was great to tell an unsolved murder mystery, but our films always have a meta theme that’s always above the obvious. In this case, there’s a lot of philosophical questions that come up when you go to these islands and you think about this story. Some of those are addressed in the writings of the protagonists from Floreana, but some of them weren’t so easy to scratch at. We knew the people on the island today knew about this and told campfire-like stories. Once we talked to those people, we found that they could actually speak to the more existential issues.

Dan: The counterweights in the movie are interesting to me. The more you know about the moderns, the more depth there is in the murder mystery. Otherwise, you could get distracted by the almost melodramatic, insane goings-on of the facts of the murder mystery story. It helps keep it focused on the psychology of why those people on the island were there and what they were thinking.

Dayna: We did do a cut of just the murder mystery, just to play with it, and it was very claustrophobic. As interesting as that story is, you need a break from it.

You have all of these components to juggle and assemble into a film somehow. Sounds like a headache!

Dan: We had a great editor! (laughs) Bill Weber edited the film, and it was highly collaborative, because it’s too much for any one person to try to pull through. It took a lot of trial and error. Bill’s an incredibly gifted editor. The team could steer this gargantuan project forward. We have work-in-progress screenings with 10-15 people who we trust to get a sense of how things are going.

Dayna: I always say to new filmmakers, don’t expect to get it right the first time. Or the second time. Or the third. It’s a process, and you’d better be patient with that iterative process if you want to make a good film.

At what point did the voice actors come onboard? Was the shape of the film already set?

Dan: By the time we started to record them, the film was at fine cut. We chose to have them read wild, meaning not to picture. They could feel their way into the roles, and we knew that we could bend the timing of the images to suit the performance. What carries the movie is the sense that these are real people talking to you. Why not let them record in a way that felt dramatically appropriate? After we fitted the footage around the performances, we could finally say we were done and give it to the composer to start playing with.

The score is so weird.

Dan: Good! I’m glad you said that. We were aiming for weird! We’d worked with Laura [Karpman] on Something Ventured, the most recent movie we made. We said, “Keep it weird.” We’d temped with weird music, like Trent Reznor. Laura said it also needed to have moments that are fully orchestral and chromatic, because this is a hybrid story. It’s a desolation story, but it’s also got romantic elements. She was able to pull both of those pieces together, keeping that essential strangeness but also introducing more lush passages. She’d do that through really cool instrumentation, with Indian glass bells, chromatic didgeridoo…

Dayna: Laura called us one day and told us she’d taken a position in Valencia, Spain at the Berkeley college of music. We were like, “How are we going to do this if you’re in Spain?!” She said to trust her and that something great would come out of it. When she got there, she’d Skype and email us and say, “I didn’t even know there was an instrument called a chromatic didgeridoo, but one of my students is an expert at playing it. I’m going to record it, and I don’t even know how we’re going to use it!” She started doing that with students from across the world.

Dan: This Russian violinist is brilliant. She plays the Baroness’ theme like someone possessed. She’s called out in the credits especially. She was roughing and temping with these riffs from her students, who were top instrumentalists, but she did write and compose a very specific score.

Do you think that because the mystery is still unsolved, the film is better for it? In other words, would it have been a worse film if you’d discovered the truth?

Dan: I like the idea that it stays mysterious. It’s not definitely solvable, but enough pieces are there that you can begin to assemble your own version or many versions of what you think may have happened. It’s not so shy of facts and accounts that you’re just left saying, “Well…I don’t know.” But you don’t get closure all the way, because wondering is half the fun.

Dayna: My favorite films are ones you want to talk about afterward. Because it’s not conclusively solved, people are going to discuss afterward in a way that they wouldn’t if we’d found the smoking gun.