Dave Jannetta and Poe Ballentine Talk ‘Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere’

In the small town of Chadron, Nebraska, math professor Steven Haataja vanished without a trace shortly after starting his new job. It took several months to find his body, and the discovery only brought on more questions. Haataja was found tied up to a tree, burnt beyond recognition, and there was no evidence of anyone else’s involvement. The case remains open to this day, with some believing Haataja either killed himself or was brutally murdered.

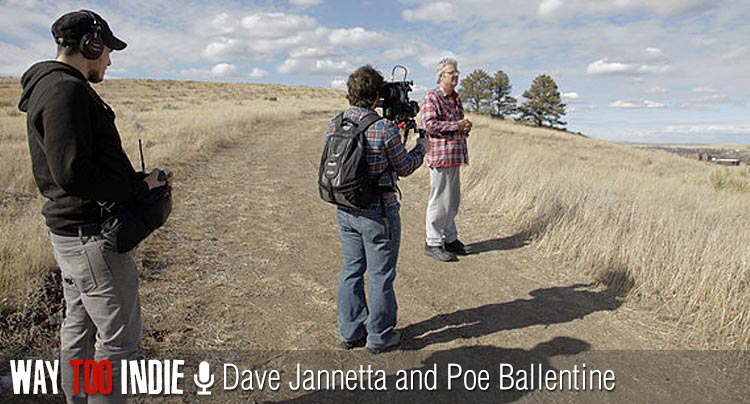

Chadron resident and writer Poe Ballantine was in the middle of working on his memoir “Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere” when filmmaker Dave Jannetta contacted him. Jannetta was interested in Poe’s memoir along with the Haataja case, and after discussions Jannetta came to Chadron to film a documentary surrounding the mystery. Ballentine weaves his own life story, Haataja’s death and the unique qualities of Chadron together in his memoir, and Jannetta uses a similar approach. Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere (the doc adopts the same title as the book) is not merely a crime story. Jannetta focuses on Ballantine’s own life, his family, and how he came to Chadron, while also profiling Chadron’s people and history.

In anticipation for the film’s world première at Hot Docs, Mr. Jannetta and Mr. Ballentine were gracious enough to answer some questions through e-mail about the film. The two men have very different personalities, but both share a mutual passion for the topics covered in their respective works. We talk about the difference between fiction and non-fiction filmmaking, the relationship between the book and film, facing obstacles while filming, what they hope the two works will achieve, and much more. Read below for the full interview.

Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere will have its world première at Hot Docs in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. You can find more information on the film here, and to find out more information about the festival (including all films playing, along with when to see them) go to www.hotdocs.ca.

Poe, your memoir was published last summer, and now Dave Jannetta’s documentary is premiering at Hot Docs. How do you feel about getting to see yourself on the big screen?

Poe Ballentine: I don’t really enjoy looking at or listening to myself, but Dave went to a lot of trouble so that I didn’t look like an idiot, so I’m going to try and be as cooperative as possible. I’m excited about the film because so much work went into it, and it’s fun to watch.

And Dave, how do you feel about getting to premiere your film at such a big event?

Dave Jannetta: After Love and Terror was accepted to Hot Docs I said to a friend, “It feels nice to be the pretty, popular cheerleader for a minute.” He thought captain of the football team was apt, but you get the idea. It’s difficult to get people to give a damn about anything and Hot Docs has definitely greased those skids. Making films independently is a slog and you can end up feeling like you’re creating in a vacuum. It’s hard to get solid, objective feedback. If festivals reject you they send form emails telling you it’s not your fault, there were just too many great films this year and “we’re sorry but we can’t tell you why yours wasn’t one of them.” You get really good at accepting rejection. I’m not positive what to expect from Hot Docs but they’ve been incredibly straightforward, helpful, and kind – exactly what a filmmaker hopes for. So I’m excited and thankful to be part of such a great festival.

[To Poe Ballantine] How did you feel when Dave Jannetta approached you about making the documentary? What made you decide to go along with it?

PB: I’m flattered anytime someone takes interest in my work, but because I work alone I thought the odds were pretty long of anything panning out between us. But he turned out to be everything you’d want in a documentarian, sharp-eyed, whip smart, funny, hardworking, detail-oriented, eager to learn, and you never knew what he might do next. I’d turn around and there he’d be in a Highland kilt, a bagpipe in his hands.

In the film, some of the people you write about in your memoir are able to speak for themselves, including your family. How did your wife and son feel about participating in the documentary? Did you learn anything new from Mr. Jannetta’s interviews with your family and the citizens of Chadron?

PB: My son is thrilled to be in a movie, my wife not so much. However I think she’s secretly pleased to be getting her beautiful mug on the big screen. Whenever you get a camera on someone and ask them poignant questions something juicy [is] bound to spill. Loren Zimmerman, the ex-LAPD homicide detective who unofficially took over the investigation, admitting that he was the most likely suspect in the murder of Steven Haataja was particularly enlightening [I thought].

[To Dave Jannetta] You’ve already written and directed one feature. Did you deliberately decide to go for non-fiction with your next film, and how would you compare the two types of filmmaking?

DJ: I often tell people that Rachel & Diana (my first feature) was my film school. It’s not a perfect film but I learned a ton. After Rachel and Diana I continued to work on narrative screenplays and was trying to make a living as a freelance filmmaker. That’s when I began thinking about possible documentary projects because it seemed to me they’d be less resource intensive but equally challenging. Then I came across a short description of Poe’s then in progress memoir [of] Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere.

I was most surprised at how the process of making narrative films vs. documentaries overlap and where they diverge. I’m not an avant-garde filmmaker, so at the most basic level I’m just trying to tell a really interesting story. It’s always the driving force. With a narrative film you basically get everything in place before you begin: screenplay, actors, locations, schedules, crew, etc. You should really be able to envision the final film from day one. Conversely, while making a documentary a lot of those things come in the reverse order. You have a vision of the finished project in mind but the capricious nature of the process doesn’t lend itself to rigidity.

Your film settles into a kind of rhythm as it goes along, going back and forth between the Haataja mystery and profiling Chadron itself. Was it difficult to develop this kind of structure during production? Did you ever have trouble in deciding what to focus on, or where it would fit within your film while editing?

DJ: Oh man – it was arduous to put it mildly. There were always three elements that were going to form the foundation of the film: Poe’s story, Steven Haataja’s story, and the story of Chadron itself. I was very familiar with Poe’s work before approaching him about doing [the film]. He spoke my language and I figured that what I knew of his life could turn into an interesting film no matter what. When we began shooting it was well before [Poe’s memoir] was published, so all I knew about it was a short description I’d read. For me, the unsolved death was intriguing but I had no clue where it would lead or how fulfilling that story thread would be. But I did know that I did not want the film to be an archetypal “true crime” documentary or procedural. And as soon as I arrived in Chadron on a scout trip and began meeting and talking to people I believed that if I could effectively capture a snapshot of what the town was like, people would find it interesting.

Poe Ballentine believes Steven Haataja was murdered, but your film gives time to different theories surrounding his death. How did your opinion on Mr. Haataja’s death develop while you were making your film, and where do you personally stand on the matter now?

DJ: It was like a pendulum. There isn’t a great deal of objective information surrounding the Haataja case so a good portion of what I was hearing was hearsay or not necessarily related to the death. But that doesn’t mean it didn’t have value. It was strange because I’d often talk with three or four people in a row who had similar opinions and it would really start to make sense. But I’d go back and look over the evidence or talk to three more people with divergent viewpoints and my opinion would flip. It’s really difficult not to suffer from confirmation bias – to have a preconceived conclusion and place extra emphasis on the evidence that supports it – but I think it’s imperative to keep an open mind to all possibilities. Occam’s razor can be helpful, but the assumptions start piling up pretty quickly and one hypotheses ends up as riddled with holes as the next. While I wouldn’t go on record saying I think it was a cold blooded murder I will say that I think, at the very least, someone else was involved or knows what happened. I realize that’s a cop-out and the fact that I couldn’t get a definitive answer is (in my opinion) a failing of the film. But life’s endings are rarely served neat and I think an ambiguous conclusion is fitting. At least for now. Steven’s story is incomplete – it’s built upon first and second hand accounts, conjecture, rumor, and a few solid pieces of evidence. But I guess that’s how history is usually written.

Since the documentary isn’t exactly an adaptation, how would the two of you characterize the relationship between the film and memoir?

DJ: I’d say the film and the memoir parallel each other and that I hope the experience of one enriches the other.

PB: Even though it has a lot of fancy writing in it, the core of my memoir is journalistic. Dave is more interested in faces, landscape, local color, and letting people talk. We’ve both examined the way in which reality is filtered and altered by whoever’s turn it is to tell a story, which explains why collaborative accounts such as news and even history itself so often miss the mark. Both of our projects are grounded in the central mystery and the portraiture of a small town reacting to a spectacularly tragic event, but I think Dave is more stylistically content with an open ending. While text gives you more room for laughs, asides, and waxing philosophical, film is better at straight exposition. We also attempt to retrace Steven’s freezing moonlit journey across private ranch land to the place where he was found, and I think the film does a better job than my book of showing how prohibitive and unlikely that venture was, at least on foot. Both of our examinations were intended to invite more information in the hopeful solution of this case. In this and many other ways I think our two projects make good companions.

Mr. Haataja’s family have publicly expressed their dislike with your documentary along with Poe Ballantine’s memoir. Since you didn’t have access to the people who knew Steven Haataja best, my question is how you, as a documentary filmmaker, try to compensate for these kinds of restrictions. How do you adapt yourself to give a fair portrayal to your subject(s)/subject matter, even if you aren’t able to include some key perspectives?

DJ: Perspective is the key word in your question. I did talk with Steven’s family early on, and their discontent with the book and film are articulated on various blogs and message boards. I had to do a lot of soul searching and tried to keep up a dialogue with them throughout the process but it’s not much fun to be reviled. Who should be able to tell Steven’s story? Is it exploitative for people who didn’t know him to undertake projects that outline some of the details of his life and death? It’s a moral grey area and I’ve had emails from people who knew Steven both excoriating me and thanking me. But that’s where the most interesting stories live. Black and white is too easy, it’s boring. It’s when the questions you’re asking are in shades of grey that you’ll tend to find the most value. All that being said – without Steven’s family on board [and for budgetary reasons] I made the decision fairly early on to restrict the perspective to the town of Chadron. Even though Steven only lived in town a short time before he disappeared I feel like I was able to find people who had an understanding of him as a person and who could communicate the essence of who he was. The tragedy of Steven is only one element of the film. If it were entirely about Steven and his death I do think [it would be exploitative].

I will say, however, that the process was made much more difficult after an edict from [Steven’s former employer] forbid their employees to discuss the case with me. This was after a meeting in which their director of communications seemed amenable to the idea of the documentary. I’ve even heard rumors that they now put something in their contracts for new employees saying they can’t discuss the Haataja case. What are they trying to hide?

The memoir wasn’t actually finished while filming took place (It was published in the summer of 2013, and you can buy a copy here). Did the filming process influence the writing process, and vice versa?

DJ: When I first arrived in Chadron, Poe had an umpteenth draft of the book that was basically shelved. He hadn’t been able to get it right, was worried about how the town would react, and was almost relieved that it was resting quietly in the shadows. He even remarked to me at one point that he hoped it could be published posthumously. I decided that I wouldn’t read a draft right away because I wanted the film to be its own entity. But I was interacting with [Poe] daily while we were filming so his ideas were seeping into the film whether I liked it or not. As I started conducting interviews he went back to his book and started [revising]. After about a year I read a draft of the book and we were able to talk more clearly. On subsequent trips we worked hard, watched movies, discussed books, ate homemade seafood étouffée, drank, and above all talked about stories. And these things, more than the book itself, impacted the actual production and editing process.

PB: Dave’s film gave me a chance to review every aspect of the case from another perspective, so it’s a much more thorough, balanced, and accurate treatment than it would’ve been without his intervention. I also started carrying around a megaphone and calling everyone “babe.”

What do the both of you hope Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere will achieve, and are you concerned with how Chadron will react?

DJ: The case of Steven Haataja’s death is still unsolved, and I think there’s more to the story. I hope that the combination of the film and book are able to knock something loose and lead to a resolution. This might not happen right away but the film will be around for people to examine. Maybe in 50 years when I’m sucking pureed brussels sprouts through a straw in a convalescent hospital someone will finally be able to put all the pieces together and figure it out.

As one of the interviewees says in the film, “If it had been a fucking football coach who disappeared they would’ve called in the National Guard.” I’ll add that if Steven was an attractive blonde female or privileged white male they wouldn’t have rested until they had all the answers. Part of the tragedy is that Steven was a quiet, gentle, cerebral wallflower. This story wouldn’t have been told if they’d found him right away. But I don’t blame Chadron as much as contemporary America. I loved it out there, made some great friends, and hope to go back often. I don’t think I portrayed anything or anyone unfairly but that doesn’t mean I won’t piss some people off. So yeah, I’m a bit concerned. But as Poe wrote to me in an early email, “It’s quite possible, since Haataja was burned alive, that there is still a killer at large, and dozens of citizens, some dangerous, will not be happy to see their accounts presented or their deeds come to light, and so the risk in this is not only artistic, but that’s of course the very quality that makes it fascinating.”

I also hope the film does its part to nudge Poe from the literary shadows. And I’d obviously like audiences to see and enjoy the documentary, to spend a little bit of time pondering the positive effect of one man’s life on a small community, the way in which facts sometimes have very little to do with the truth, and that the truth is gossamer anyway.

PB: Mr. Jannetta and I have discussed this extensively. We both want standing ovations and frenzied women ripping off our clothes. We’d also like to put Chadron on the map and prove once and for all that the place called Nebraska really exists. As with the book, most will be pleased by the documentary, but there will be grumps, rubes, dorks, loafers, and killers who’ll choose not to like it. Vive la difference!