Charlie and Lucy Paul Talk Ralph Steadman, ‘For No Good Reason’

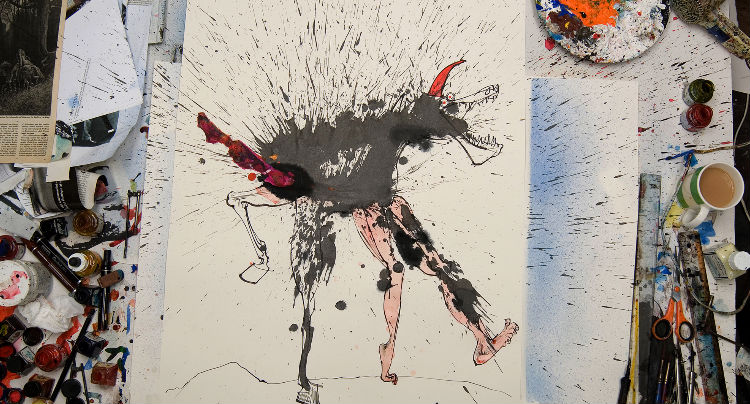

In Charlie Paul’s For No Good Reason, the British filmmaker allows us a peek into the world of artist Ralph Steadman, one of the key Gonzo visionaries and good friend of Hunter S. Thompson. The film chronicles not only his career, but his artistic method, capturing the way Steadman slaps the canvas with paint and manipulates the splatter until it resembles something out of a fever dream.

Paul and his wife Lucy, the film’s producer, sat down with us in San Francisco to talk about recording Ralph’s artwork for 15 years, Ralph’s hatred of drips, crafting an unconventional film for an unconventional artist, emulating Ralph’s artistic process in filmmaking, and more.

So you had this idea of recording Ralph Steadman before it was possible technologically?

Charlie: Absolutely. The reason the whole film came about was that I was actually shooting this process on film. And I went to Ralph because I heard he had shot his art with camera above his desk that he could record with by pressing a button. It was fascinating.

So I asked him if I could record him with this camera above his desk and if every time he did a [painting] he would press a button to start recording. Ralph, being a great embracer of technology, said he would try it. And that was 15 years ago. Ever since, every picture Ralph has ever made has been recorded using this process.

His artistic process is incredible. Can you remember the first time you saw him at work and what that was like? It’s unlike anything I’ve seen.

Charlie: Well, it was quite shocking to be quite honest. Other artists that I have worked with would paint away with a constant process. Ralph is explosive is in his art. He stands up there, he whacks it down. As the ink’s moving around, running down the page, he manipulates it and adds scratches and that kind of stuff.

Lucy: It’s a very live exchange between him, his canvas, and his creation. It’s a real live communication between him and the page.

Charlie: We do a great Q&A with Ralph. We’re doing one with Pixar tomorrow. He’s on Skype with a laptop in his studio, and within 15 minutes he will whack a picture out. It’s fantastic to watch. You basically have to lift his art very carefully so it doesn’t drip. He hates drips.

He hates drips?!

Charlie: He doesn’t like drips. You might have noticed it’s all full of splatters. He loves splatters. So you have to be very careful how you move his art from the table. So while it looks like Ralph is out of control, he is actually it’s a very controlled process.

His art is explosive, but he doesn’t seem like an explosive kind of guy. Talk about that juxtaposition.

Charlie: That is Ralph. Ralph is the man you see in the film. The objective of the film is to show the difference between the two. Ralph is lucky that he has a way of expressing what is going on inside. So I guess if he didn’t have his art to offload those ideas, he might become an angry and volatile person. But Ralph is a very stable, warm, and generous man who is a pleasure to be around. Not a dangerous man like Hunter would have been for example.

Can you both tell me a story about you and Ralph?

Charlie: After [being around him for] 15 years, you have a lot of memories. [Laughs] For me, seeing these sentimental pieces of art appear out of nowhere was, as a filmmaker, the most amazing privilege to come across. The highlight of any given day was for Ralph to create a piece of art that I knew would make it into the film.

Lucy: He’s quite unpredictable. He’s very warm and generous, but he is a little bit crazy as well. So in a way it’s not the kind of big stories; it’s just those little moments.

Charlie: The other fantastic thing about working with Ralph is that he is never parted with his art. It’s always in the studio. He only sends out reproductions to magazines and so on. So on a regular basis I would open a drawer and in there would be a piece of art which I haven’t seen for 30 or 40 years. For me it was mind blowing.

The subject matter demands the documentary not be conventional. Talk about the style of the film and doing him justice in that way.

Charlie: I made the film to reflect Ralph’s art. And Ralph’s art is full of scrappy bits and pieces. Ralph would use montages, center-tape, ink, paper, and draw things and stick things. So that was a technique that I felt I had to use. The film is full of bits of edge-of-frame and clapper boards because that is Ralph’s art. I had to make the filmmaking process the same as Ralph’s art-making process if I was going to reflect Ralph’s art.

You’re right. On top of that, the idea of making a conventional film about an unconventional artist would have been defeatist in the first place.

What was the point through this 15 year process that you thought this had to be a film, not just a recording of him painting?

Charlie: I wanted to the film to be like a piece of art. So I recognized if the work I was going to do was to reflect Ralph’s art, it would have to be in a medium that was a standalone medium, much like Ralph’s art is standalone art. So that’s how I realized it was going to be a film rather than a TV documentary.

Lucy: [To Charlie] When you first started out, you weren’t making a film necessarily. You were just recording and observing your artistic hero. Probably about 5 years ago, the people that we work with and myself said, “Charlie, this is phenomenal footage you’ve got here. We need to make film out of this!” Then the process started with more seriousness in producing a specific outcome.

The editing process took about 3 years. Because Charlie works in such a visual way, it was difficult to find an editor that Charlie was going to respect was willing to let go of this project that was so personal. So we interviewed quite a few editors.

You’re so fortunate that you’re friends with Ralph and that your access to him is so unprecedented. Was there a measure of fear that, because this film was such a long process, it had to be spot-on in reflecting who he is?

Charlie: I think it was the amount of time I took to make the film which allowed it to be so spot-on. If you have a schedule that you have to meet then you have to bridge gaps and try to make things up. I was fortunate enough that, if there was something in the edit that wasn’t delivering, I could go back to Ralph and discuss what we could do to fill that gap. So Ralph might respond with a painting or give a bit of advice. It allowed the film to end naturally.

Lucy: And also with Ralph, there isn’t a way that you can get him to do things. If you point him one direction, it’s almost like a natural instinct for him to go the other direction. So really you were observing, not pushing him one way. There was no comprising.

Charlie: Absolutely. Ralph definitely drove the artist creation within the film. So my job was to find a way to make a cohesive film. It took a long time because if I wanted something specific, I couldn’t ever ask Ralph to do it. I would just have to wait for it to naturally evolve.

That’s interesting because the way you describe that process sounds like his process.

Charlie: Absolutely. My clear objective in the film was to represent Ralph’s art and his process as closely to his art that filmmaking could be. So in the same way that Ralph will let the splat lead his way, each day we filmed I let Ralph’s first intention dictate how that day went. Therefore, it was a privilege was a filmmaker to be led that way rather than be worried about to fit your film. That was never a concern.

What characteristic of Ralph’s do you identify with most?

Charlie: Ralph’s unrelenting efforts to make the world a better place is what attracted me in the first place as an artist. I think Ralph’s integrity and his intention is one of the greatest things an artist can have.

The music in the film suggests that you’re aiming at a younger generation. Was that important to you?

Charlie: Absolutely. Ralph has been around for many years and many people know about Ralph through the times of Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and all of the classic books that Ralph has worked on with great literary artists of our time. So for me it was about making Ralph accessible to a new generation. It was very important to me to make Ralph contemporary and not just someone of the past.

Lucy: The message of his art holds such resonance for young people today as well. Because he is very live and very current. He’s still commenting on what he feels about the world today.

Charlie: Yeah. And the wonderful thing about good art is that it’s not tainted by time. Pieces of art that were made 40 years ago are as fresh today as they were then. So there was no reason to treat Ralph’s art like archive material. It’s relevant, current art. So that’s what I thought that a younger audience will appreciate this as much as an older audience, so to exclude them would be the wrong thing.

Have you had conversations with young people who saw the film that weren’t familiar with any of his concepts?

Lucy: Yes. They were blown away by it.

Charlie: Yeah, it’s been a marvelous thing to introduce Ralph to a new generation. It’s an honor.

Are you still recording him?

Charlie: Yes. I saw him last week and he still has the camera above his desk. I’ve given him one button to press, so when he goes into the studio and press the button, all the lights turn on and the camera activates. He still does this process. He is creating more now than he has in years.

What’s great about this process of him pressing the button and taking these shots is that it reveals a new dimension to his art that you can’t see by simply looking at the final product.

Charlie: Yeah, he is as amazed as I am by the process. Artists forget what they are doing as they go along. They’re absorbed in the moment. That process is important to me because coming out of art college I was disillusioned with the way films were representing artists. The habit is to move around a finished painting, often with a third-party describing what you’re looking at. I always felt that wasn’t the artist intention, to have a critic describe the finished process.

Here, the pace of the film is dictated by the artist. He can press the button lots of times and the film slows down, if he does one it speeds up. So the artist has full control in the medium he is working in. And it’s been great to take it to Ralph and have him respond in his own way.