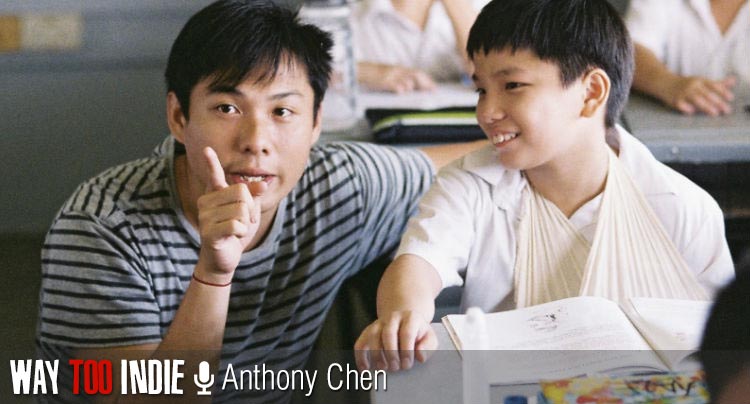

Anthony Chen Talks ‘Ilo Ilo’, Protecting His Humility

Singaporean director Anthony Chen is riding quite the wave of success with his feature debut, Ilo Ilo. The film won the Camera d’Or at Cannes 2013 and garnered many more accolades and awards following its smashing premiere. The film follows a strained Singaporean family whose relationship is stretched further when they must adapt to a new Filipino domestic helper named Teresa joining their household. Teresa develops a close bond with Jiale, the young boy she cares for daily.

We spoke to Chen at CAAMFest 2014 about why it took him so long to make his first feature, growing up with a domestic helper, the film’s success, his wife saying he’s difficult to live with, his stubbornness making him a better director, and more.

You won the Camera d’Or at Cannes 2013, which is a big deal for a Singaporean film.

Anthony: It was a big step for Singaporean cinema. Camera d’Or is a prestigious prize, and it’s the first time a Singaporean feature film has won an award at Cannes. I’ve had a very good outing each time I’ve been to Cannes. In 2007, I had a short film in competition, and it became the first Singaporean film to win an award at Cannes. In a way, I think Cannes has been very, very special for me. Cannes probably gave my my career as a filmmaker.

You made ten short films before making this feature.

Anthony: Yes, ten shorts. I’ve made a lot. My first short was made in 2004 when I was 19-20. It was my graduation film from film school. My shorts have done rather well in major festivals. Shorts have been very fundamental in shaping me as a filmmaker and honing my craft as a director. It’s given me a lot of confidence as well from one film to the next. When you get a good critique, that’s when you feel, “Perhaps I do know something about filmmaking.”

So you did shorts for about eight, nine years. Why wait so long to do your first feature?

Anthony: I didn’t feel I was ready at all. In fact, there was an opportunity in 2007 to do a film, after my short won at Cannes. Everyone told me, “Strike when the iron is hot!” That short opened a lot of doors. But I was quite young at the time. I was 23, and I didn’t feel I was ready, so instead, I went back to school in the UK and did a two-year masters in film directing. I wanted to train myself and mature much more before I was ready to take that next big step.

I imagine, with the mindset of, “Am I ready? Not yet,” you must have put a lot of pressure on yourself to make your first feature as good as it could be.

Anthony: I think it was important that mentally and spiritually I felt, “The time is now.”

My parents are from the Philippines, and my mother grew up with a domestic helper. You grew up with one as well, an experience that inspired the film.

Anthony: I think it’s something this part of the world doesn’t really get. A stranger comes into the family, working as a servant, but she very much becomes part of the family. She isn’t like an au pair who comes in during the daytime or during nights when the parents aren’t free; she literally lives with you. In Singapore, because of space constraints, the nanny usually sleeps in the same bedroom as the children. It’s a very intimate, personal connection. What’s fascinating is, the children probably have a much stronger bond with the nanny than the parents. The parents are always busy working.

Your work is very observational, and you seem to have a knack for identifying people’s behavior. Does this skill help you in everyday life to become a better functioning person in society?

Anthony: That’s a great question, but I’m pretty sure the best person to answer it is my wife! She’d probably say, “NO! He’s so difficult to live with!” [laughs] She’s always telling me: “I just don’t get it. You’re always making such delicate, sensitive films about humanity, but you’re so difficult to live with!” I’m very obstinate. I’m very stubborn. I want things my way. I think I see things. I think I’m very sensitive to people and their actions and nuances and emotions. But I’m equally as flawed as the characters in all my films. I think that’s why humanity is worth celebrating. We’re flawed. I don’t believe that just because you understand relationships that you become some kind of saintly person or something. You wish it was like that [laughs], but it’s not the case.

Does your stubbornness make you a better director?

Anthony: I guess so. I’m very obsessive-compulsive when I make my films. I grasp very tightly on what I’m working on, and until I make sense of what it’s about, I don’t let go. It’s very tense. It’s interesting. A lot of critics have told me that I have a very accurate observation of the female psyche. My wife disagrees with that as well! [laughs] “If you understand women so well, why don’t you understand me!” The truth is, because I understand her so well…whatever she wants, I don’t give. [laughs] I can be very manipulative.

You won the award for Best Film at the 50th Taipei Golden Horse Film Festival. I understand this is a big deal for a Singaporean film.

Anthony: The Golden Horse has a real legacy. It’s always been known as the Chinese Oscars; it’s beamed to 1 billion Chinese-speaking people all over the world. It’s crowned well known filmmakers like Ang Lee and Hou Hsiao-Hsien. For the longest time, Singapore hasn’t been on its radar. What was a real pivotal change was when our film garnered a record six major nominations and went on to win four. All of a sudden, it made Chinese audiences look at Singapore differently. We’ve been excluded for a long time because we’re an English-speaking country and a multi-racial country.

What is it about your film that’s caused it to break through these barriers?

Anthony: I think it’s the themes in the film that made something that was very culturally specific much more universal. Coming-of-age, family, economic crisis, migration; these are themes people deal with all over the world. I’m beginning to feel this because the film has had such an incredible journey since Cannes. My sense is that, what really connects the film with audiences is that there’s an honesty to the film that feels genuine and not fabricated or manipulative. There were critics telling me that, one reason the film did well at Cannes was that every other film was trying to do something, trying to show off in terms of style, cinematography, subject matter…there’s a lot of gusto. This was the only film that wasn’t trying to do any of that–it doesn’t try to be something it’s not.

You’ve lived in London for a few years now.

Anthony: I actually met my wife in London. I think I can see myself staying in London for a long, long time. It’s a very inspiring city. It makes you feel very small, because there’s so much talent all around you. Just like New York, it’s a city for the arts, with music, theater, cinema, visual arts, museums. What’s amazing is, every time you go out, you feel like there’s so much genius and talent around that whatever you achieve won’t be enough for the city.

You like that feeling.

Anthony: Yes, I do. I feel constantly challenged and put down. You have to struggle and keep going as an artist. It forces you to constantly grow and reinvent yourself. I do like that feeling. It keeps you humble.

What have you learned from Ilo Ilo as a director?

Anthony: It’s allowed me to get a grasp on the international film business. It’s very interesting that a director is talking about the business end of things, but for the first time I saw how things work. I understand how it works when a film ends up selling to different territories around the world. Making shorts for a long time, I was thinking that the short was the short, and then I went to festivals and it was over. It’s almost like I hadn’t come of age as a filmmaker, and then I realized that there is this much bigger community out there, and there’s a certain way films work.

You’ve been on an incredible streak with Ilo Ilo, touching people across the world and winning awards along the way. You were talking about the film being successful at Cannes because it doesn’t beg to be loved; you weren’t grasping at awards as you made the film because you were humble. Will it be a challenge, following the success of this film, to maintain that humility and not strive to capture that kind of notoriety again? How will you stay grounded?

Anthony: I’ve been thinking about that for a long time. My challenge on the next film is to protect my attitude and my values toward filmmaking. I have to find that very raw, undaunted passion for making films. How can I continue to be naive and stay true to myself? Now, I’ve got lots of scripts being thrown at me. The doors have opened, and there are times when I feel like, “Should I do it?” I hope that I can preserve my mentality toward filmmaking, but it really comes from here [points to chest]…from the heart. We’ve seen a lot of auteurs meander around in their careers because all of a sudden there was a lot of money and opportunities. I’m hoping that, with my second and third film, there will be the same sense of me as a filmmaker, the same directorial integrity. I think it’s very important that my films have real heart.