Oscar Travesties: 10 Great Films That Should Have Won Best Picture

It’s almost Oscar time again, and I’ve followed the Academy Awards for long enough now to know that they don’t always represent the quality and scope of the year’s best movies. Yet, there’s something about the award season’s glitziest bash that turns me into the film buff equivalent of a WWE fan, who knows deep down that the fighting isn’t actually real, but can’t help going mental when the contenders start hurling themselves from the top turnbuckle.

In anticipation of the 88th Academy Awards nominations, here’s a list of Oscar’s worst and weirdest oversights in the Best Picture category.

10 Films That Should’ve Won Best Picture

#10. Pan’s Labyrinth

Dark-hued, dangerous and melancholy, Guillermo del Toro’s visionary fairytale grows in stature year by year, already looking like one of the films of the young century. It is a deeply textured masterwork, creating a fully realised reality and alternative reality for its young heroine Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), who seeks refuge from the horrors of post-civil war Spain in a fantasy world, only to find it as dark and violent as real life.

Evoking the primal, ancient morality tales of old rather than the sanitized hokum of Disney, it strikes a resonant chord in our deepest wishes and fears. It was probably a bit too obscure for voters—foreign language films rarely get much recognition in the Best Picture category, although lightweight fare such as Il Postino has made a showing in modern times. Martin Scorsese’s The Departed took Best Pic, and it had the misfortune to go up against the excellent The Lives of Others in the Best Foreign Language Film category. I’m sure time will separate Pan’s Labyrinth from both movies significantly.

#9. Pulp Fiction

Quentin Tarantino’s burst of pure cinema is arguably the most influential film of the past twenty-five years. It changed the way people made, wrote and thought about movies ever since. Two decades later, QT is an auteur who can make whatever he wants, please the critics (most of the time), and pack out theatres across the world. Hell, he could even adapt his grocery list for the screen and it would still be a hit.

Pulp Fiction was the perfect blend of attitude, style, music, dialogue, set pieces, dance moves, top shelf performances, and sheer, balls-out bravado. It was sensational, and struck at exactly the right time.

#8. Field of Dreams

The 62nd Awards were arguably the nadir for Oscar, with the twee Driving Miss Daisy beating a strong field including Born on the Forth of July, Dead Poet’s Society, My Left Foot, and my pick, Field of Dreams to Best Picture.

You don’t need to be a baseball fan to be enchanted by this tale of Iowa farmer Ray Kinsella (Kevin Costner), compelled by ghostly voices to build a baseball diamond over his crops. Told straight and featuring Costner at his most disarming and sincere, it’s a wonderful piece of modern myth-making. It’s a film about nostalgia and regret, but also an optimistic, magic hour celebration of the dreamer in all of us.

#7. The Killing Fields

Losing to Milos Forman’s grandiose, gaudy and rather campy Amadeus, Roland Joffe’s The Killing Fields is an impassioned yet sensitive depiction of the apocalyptic Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. It’s centred on the relationship between two journalists, American Sydney Schanberg (Sam Waterson) and Cambodian Dith Pran (Dr. Haing S Ngor) caught amid the brutal regime change.

Working from a grown up screenplay by Bruce Robinson (Withnail & I), Joffe captures the chaos and turmoil of those years in great detail, with escalating panic as the US ditches its Cambodian allies. Schanberg is reluctantly forced to follow suit, leaving Pran to fend for himself in Year Zero. Ngor’s dignified, resolute performance is humbling—a first-time actor, he survived the ordeal in real life before making it to the States in 1980.

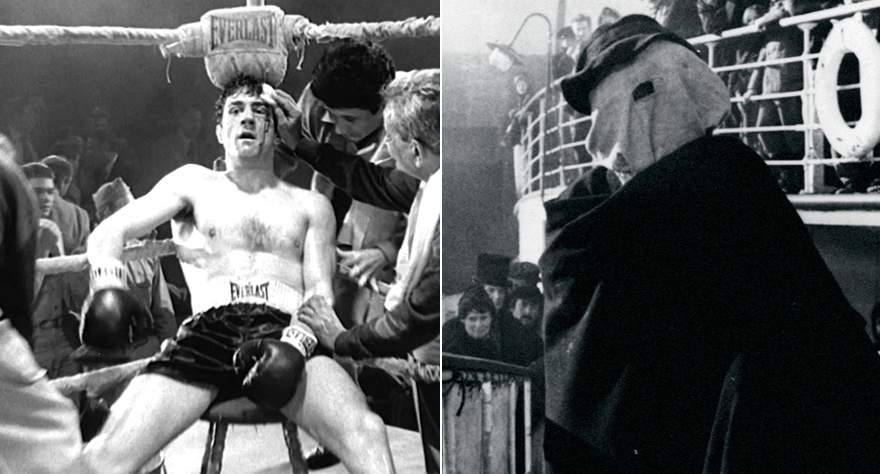

#6. Raging Bull / The Elephant Man

Take your pick, either film would have been a worthier winner than Robert Redford’s Ordinary People, which no one has seen since it took the Best Picture trophy at the 53rd awards. Both biopics shot in wondrous black and white, Scorsese and David Lynch’s films examine opposite ends of the human spectrum—Robert De Niro’s repugnant, self-destructive Middleweight Champ Jake La Motta, and John Hurt’s gentle and intelligent John Merrick, trapped inside a hideously deformed body.

Raging Bull is brutal and depressing, The Elephant Man ethereal and heartbreaking. Both have become modern masterpieces.

#5. The Exorcist

William Friedkin’s iconic horror has lost some of its shock value over the years, and I think it is all the better for it. Once you’re over all the head-spinning and spider-walking, you can concentrate on the story itself, and it always amazes me each time I see it how positive the film is. The Exorcist is a good movie in the purest sense of the word, and I think that you can draw encouragement from it no matter what your theological standpoint.

If you’re a person of faith, it makes great propaganda for the church, showing the Devil as crude and debased, while God’s humble servants selflessly lay down their lives to save a possessed little girl. If you’re agnostic, you can be buoyed by the sheer decency of the human characters in the film. If a bomb goes off in a public place, there are always people who run towards the explosion, disregarding their own safety in the hope of saving others.

That’s what the characters in The Exorcist are like, especially old and dispirited Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) and young and doubting Father Karras (Jason Miller)—on blind faith they ride to the rescue with no evidence that God has their backs. Despite its diabolical reputation, I find The Exorcist such an incredibly uplifting film.

#4. Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Like Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick didn’t get much love from the Academy—between them, they won a grand total of zero awards for Best Director. 2001: A Space Odyssey wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture, but I’m listing Dr. Strangelove because I absolutely hate the film that beat it, George Cukor’s smug, shrieking My Fair Lady. (Interesting side note: Audrey Hepburn sported one of two dodgy Cockney accents in the Best Pic category that year, along with Dick Van Dyke’s chimney sweep in Mary Poppins.)

Perhaps coming a little too soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Strangelove‘s acerbic satire has become synonymous with the insanity of war. Comedy madman Peter Seller’s three performances are rightly celebrated, but it is the supporting trio of Sterling Hayden, Slim Pickens and George C Scott that really stick with you, ultra believable as crazed military men deliriously willing to push the world over the brink of mutually assured destruction to get one over on the Ruskies. Kubrick observes all this madness with a sardonic, deadpan gaze, and the film concludes with one of the most terrifyingly beautiful scenes of all time – the end of the world set to Dame Vera Lynn’s We’ll Meet Again.

#3. Vertigo

No popular filmmaker quite flaunted his kinks and fetishes on the screen quite as obsessively as the Portly Pervert (aka Master of Suspense) Alfred Hitchcock. Vertigo, his most personal vision, was met with a mixed reaction by critics and making little impact at the Oscars, only picking up a couple of technical awards.

These days we’re all amateur psychologists, so I think the modern audience is better positioned to appreciate Hitchcock’s masterpiece. It’s the eerie, twisted tale of a detective ruthlessly shaping a shop girl into the object of his obsessions, an icy blonde (what else in Hitchcock?) that he couldn’t prevent committing suicide because of his fear of heights. James Stewart is magnificent, tainting his good guy image to queasy effect.

#2. The Third Man

Orson Welles already had the greatest film of all time under his belt (Citizen Kane), and a few years later he gave us the greatest movie entrance of all time in Carol Reed’s funny, thrilling and fatalistic The Third Man. We follow Joseph Cotten’s gullible pulp novelist through the noirish, expressionistic underworld of post-war Vienna in search of his old best friend Harry Lime (Welles), wanted by the authorities for peddling dodgy penicillin. Anton Karas’s fabulous zither theme perfectly captures the tone of the film, managing to be jaunty and slightly sinister at the same time. A thing of joy.

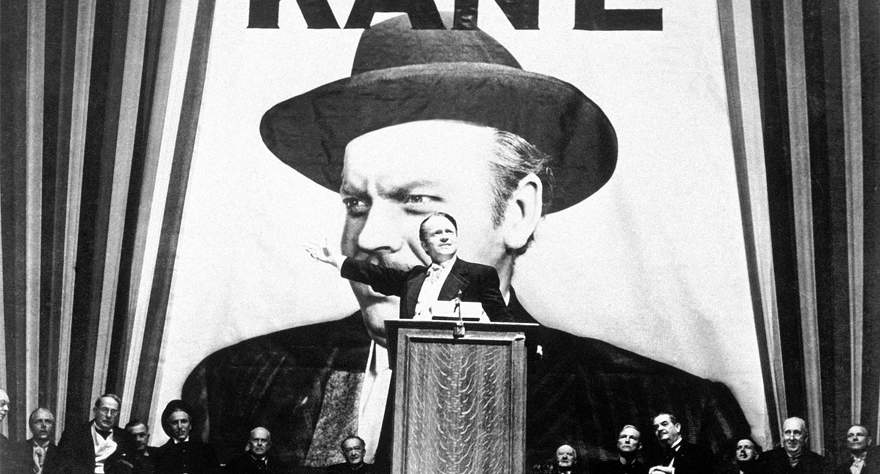

#1. Citizen Kane

Although regarded as a cornerstone of modern cinema, Orson Welles’s masterpiece lost out on Outstanding Motion Picture to a film well-regarded but little-seen these days, How Green Was My Valley. Maybe it isn’t so difficult to see why – the Oscars have always been a popularity contest, and I think you need to be a bit of a cinephile to get the most out of Citizen Kane. The film is like Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu, a magnificent, chilly mausoleum to its creator’s limitless talent, ambition and vanity. A miraculous piece of film making, but there’s little warmth within.

Also worth mentioning is another losing Best Pic nominee at the 1942 ceremony, a tight, atmospheric detective thriller called The Maltese Falcon. While small in scope, it crystallised our notion of noir, and its influence can be seen in movies as diverse as Chinatown, Blade Runner and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?