Kanye West, Terrence Malick, and the Price of Auteurism

When examining two artists’ work, writers rarely consider jumping across the media barrier to study themes and trends in art as a whole. Artistry isn’t limited to one form of multimedia, and auteurism can be examined between novelists, filmmakers, musicians, and/or playwrights. After listening to Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo and watching Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups, I couldn’t help noticing similarities in the static energy of both projects, whose many moving parts turned into commotion. Although Malick and West’s creative processes are worlds apart, their evolution as artists can be seen as parallel as they explore spirituality, perfection and challenge the notions of art itself in their polarizing careers. But when comparing their recent output, it seems that they have taken one step beyond the apex of their highest artistic potential. The Life of Pablo and Knight of Cups are problematic works due to how involved they are in their own space, whether it be Malick’s cold, dreamy world or West’s personal heaven—empty of consequences. Both projects present a false sense of grandeur that falls apart on the principle of a weak foundation.

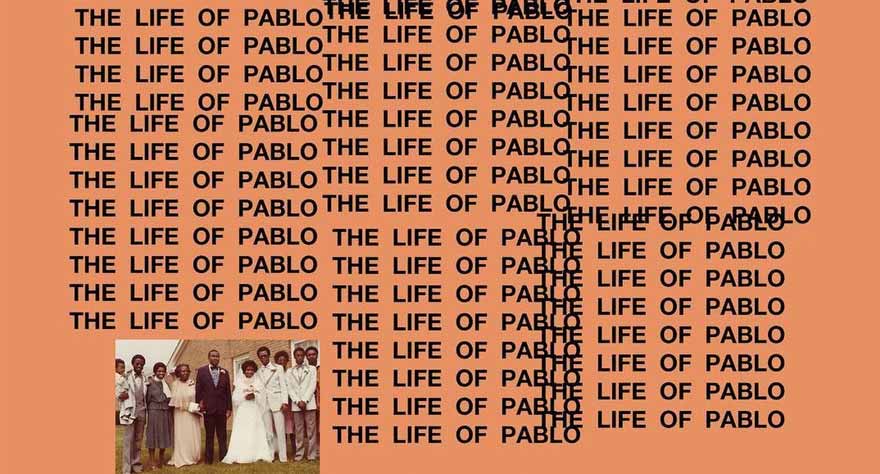

The titles of both The Life of Pablo and Knight of Cups allude to conceptually grand pieces doused in imagery and inspiration. After many assumed that West’s album was alluding to Pablo Picasso or Pablo Escobar, it was a bit of a surprise when West hinted that the titular Pablo may be St. Paul the Apostle. Yet, despite what the album promises, The Life of Pablo gives very little insight into the life of any Pablo, whether it be Picasso, Escobar, the Apostle or an alter-ego of West. In fact, the album meanders from track to track in a shallow and sometimes chaotic way. My first concern when listening to the much tighter 10-track album that premiered at Madison Square Garden was that Pablo wasn’t conceptually innovative unlike Yeezus or My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. That concern is even more grounded in the final album, which includes a lot of songs that feel like bonus tracks.

Knight of Cups central idea is much clearer, but not necessarily better in execution. Malick uses tarot card readings to characterize and split his film into chapters. The Knight of Cups tarot card comes from the “Minor Arcana” deck; when the card is upright it represents opportunities, changes, and new romances, but when the card is turned downward it represents recklessness and a person who has trouble distinguishing right from wrong. Knight of Cups follows Rick as he attempts to flip his attributes while meeting other individuals who represent different cards from the deck. Each of the first seven chapters, all named after a card in the Major Arcana deck, show Rick meandering between romantic flings and family members before finding his inner peace. His turmoil is cleared in the eighth chapter, called “Freedom.” Here, the tarot card concept comes to an abrupt halt—“Freedom” isn’t even a tarot card, yet many of the unused cards could’ve represented the same ideas of Malick’s final chapter. Ultimately, Malick captures the ideas of the cards as superficially as West creates a “Life” for any of his titular “Pablos.” Both works are sprawling and sometimes random, but they’re missing a central, cohesive idea. Though the works never hit a conceptual grandeur, they aren’t thoughtless and have some conceptual ingenuity.

When Knight of Cups and The Life of Pablo reach their thematic potential, they often focus on the same things: spirituality and a quest for perfection or redemption. These are some of the same themes that Malick and Kanye have tackled throughout their careers.

Malick’s work has always been upheld with inspiration from spirituality and religion. The Tree of Life is the epitome of his theological questioning, but To The Wonder and Knight of Cups also examine religion in their exploration of men lost in the worlds they inhabit. Knight of Cups’ spirituality and mystery doesn’t always lend itself to Christianity, but its opening lines come from The Pilgrim’s Progress, a Christian allegory written in 1678 by John Bunyan.

West isn’t unfamiliar to large productions sampling from a multitude of sources; speeches, sermons, and classic songs show up in some form or another throughout The Life of Pablo, along with dozens of other samples. The Life is Pablo’s opening track is “Ultralight Beam,” the most holistic and singular song of the album, which borrows from an Instagram post of a little girl saying, “We don’t want no devils in the house, God.” These words, which open the album, are unexpected from a rap album or a Kanye West album, but they mark a message that is revisited multiple times on The Life of Pablo. “Ultralight Beam” continues in a spiritual direction and, at times, nearly breaks into full gospel, whether it’s because of lyrical content or an actual gospel choir.

In relation to spirituality, West and Malick also explore a divinity in their own characters or personas. In the rap community, West is sometimes viewed as a god. This maybe indicates why The Life of Pablo features an enormous amount of other performers—work from his “disciples.” And while West has stated he’s a Christian, it’s a statement that comes with controversy after tracks like “Jesus Walks” and his album Yeezus, where West often paints himself as a false profit.

On the other hand, Malick takes no claim to be a god among men, but a theme throughout his work is a quest for perfection. This could manifest in striving for a perfect marriage in To The Wonder; a perfect walk with God in The Tree of Life; or Rick’s journey for divinity in Hollywood while finding redemption in Knight of Cups. At Malick’s best, his characters are human and their wonderings are relatable, but this theme of perfection actually provides ammunition to his detractors. Christian Bale wandering through Los Angeles meeting with countless women is, understandably, seen as pretentious and not insightful to the real everyman. Ben Affleck searching for true love through Rachel McAdams or Olga Kurylenko amid airy whispers in To The Wonder comes off as equally shallow and disengaged.

The Life of Pablo and Knight of Cups are hugely spiritual works, albeit in hugely different ways. West’s inward spiritual examination is more on the nose and ironic than Malick’s, yet it is clear that West and Malick take inspiration from a theistic entity—presumably a Christian one—that drives them into exploring divinity or the futility of perfection, respectively. As strong as these ideas were in previous Malick and West joints, it is hard for me to perceive their recent outputs as anything but slight.

Once upon a time, I wasn’t just a casual fan of West and Malick’s work, but their latest offerings have left me questioning their visions and career trajectories. My biggest complaints about their latest work actually relate back to the way the artists react with their audiences when they aren’t behind a camera or a microphone.

Malick’s dissociation from the public eye is evident in his most detached work yet. With Knight of Cups, Malick has lost the touch and understanding of the human condition that actually drove his earlier works. Instead of capturing a relatable story with real characters, Knight of Cups meanders and searches, but the exploration is never more than a surface deep perspective of an uninteresting man.

On the other hand, The Life of Pablo is an album of the moment that’s caught up in the zeitgeist. This is as much of reflection of West’s inward interests as it is a reflection of his every (unfiltered) thought. At times, The Life of Pablo becomes a misaligned musical rant that throws too many half-fleshed out ideas in the form of samples and guests instead of coherence and quality. The album, at its worst, could be compared to West’s twitter persona—scatterbrained, both musically and lyrically.

The Life of Pablo and Knight of Cups both reach moments of grandeur, but these moments only point to a greatness that is usually absent throughout the rest of their works. My initial response to The Life of Pablo was mixed, and as I continue to listen to the album I find it more problematic (but that still hasn’t stopped me from listening). Inversely, my only viewing of Knight of Cups was a chore that left me bored and irritated, but I find myself thinking about it more often than I anticipated.

At the heart of both works is a problem with auteurism. I have previously mentioned that both pieces serve as the strongest sense of vision from the artist, but this vision doesn’t translate into a language most audiences can understand or necessarily want to hear. Yet, on the other side of the spectrum, auteurism bolsters the careers of West and Malick, driving the creativity in both of their recent outputs. The Life of Pablo and Knight of Cups don’t work due to a lack of effort; Malick and West’s visions get lost on a large portion of their intended audience because they are too consumed in their own art.