Invasion of the Indie Snatchers: Hollywood’s Assimilation of Independent Cinema

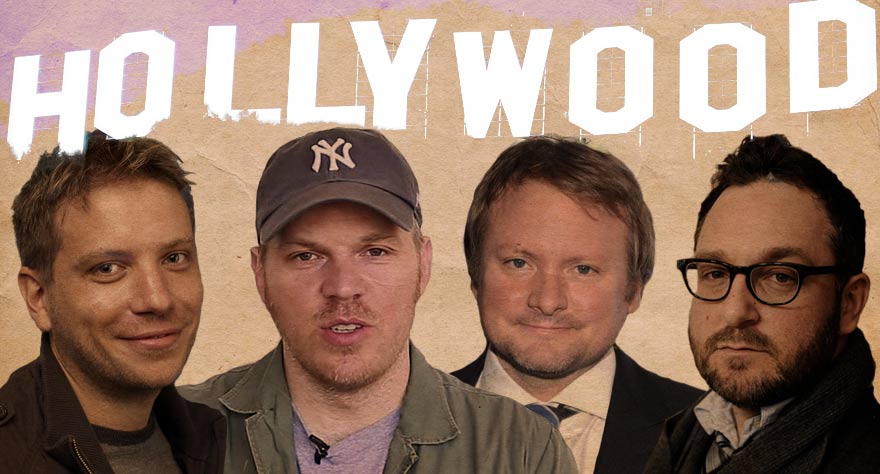

For fans of independent films, now might be the time to feel vindicated. The transition from the realm of indie to the studio system isn’t a new concept by any means, but in the last several years cutting one’s teeth on the festival circuit has become very lucrative for some directors. Gareth Edwards went from making the low-budget Monsters in 2010 to helming the Godzilla reboot 4 years later (and in doing so went from a 6-figure budget to a 9-figure one); Marc Webb leapt from the twee (500) Days of Summer to taking over Sony’s Spider-Man reboot The Amazing Spider-Man; James Gunn went from R-rated genre fare to handling Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy; Rian Johnson, who already made a big leap from Brick to Looper, launched into the stratosphere when he was picked to direct the 8th episode of Star Wars; and most recently, Safety Not Guaranteed’s Colin Trevorrow followed up his début with none other than Jurassic World. The glamour of Hollywood is merging with the not so glamorous world of DIY filmmaking, and it’s clearly working out for both the directors and the studios.

It’s natural to wonder how the influx of relatively new directors from festivals like Sundance or SXSW might change the blandness of Hollywood tentpoles, but it might be better to start asking about the other side of this equation. What does this mean for independent films, and will it change the way we perceive indies? Independent films don’t have an industry as vast or profitable as the studios, which means that the indie “system” is much more malleable and, therefore, easier to change.

And it’s evident that, despite the financial success of films like Jurassic World and Godzilla, artistic success is hard to find in this new trend. The boundaries between mainstream and independent have been slowly merging together, but the entire idea of indie has been about separating from the mainstream, and providing an alternative to films designed by committee. What’s happening now is a slow, disparaging shift in what indie means, and an increase in power and control for Hollywood. Indie directors aren’t infiltrating the system; they’re being devoured by it.

Jurassic World and Godzilla

That hasn’t always been the case. The early ’90s saw the success stories of Quentin Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez and Kevin Smith. For those three filmmakers, their situation was the ideal. Rather than adapt themselves to the status quo, they were able to apply their distinct styles on a bigger scale. But the film industry is a different beast today. Tarantino, Rodriguez and Smith directed their own original stories and didn’t work with a massive budget. Today, directors are getting scooped up to take over other people’s properties, and the budgets go well past 100 million. It’s nice to think that a certain filmmaker’s unique or irreverent style might successfully port over to the sequel/prequel/reboot/adaptation/etc. blockbuster, but it’s not likely. Investors would be insane to hand over that amount of cash to someone who’s only worked with a small fraction of that money.

All someone has to do is watch what’s been released so far to see how much these director’s distinct qualities from their earlier work(s) have been drowned out by the wants and needs of those truly running the show. Watch Godzilla, or James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, and it’s like playing a game of “Where’s Waldo?” with directorial trademarks. Gunn may have been able to cast Michael Rooker in a supporting role—a part that could have gone to anyone and no one would have blinked—but Guardians follows a very clear, familiar and formulaic path, one that also helped Marvel continue building the overall story for their massively successful franchise. It didn’t come as a huge surprise when rumours started that Edgar Wright, one of the best genre filmmakers working today, bailed on Ant-Man because Marvel wanted a Marvel movie, not an Edgar Wright movie.

So this brings me back to the first question I asked: What does this mean for independent films? What this new trend has done is turn film festivals like Sundance and SXSW—places designed to celebrate and promote distinct, independent voices—into training grounds for the next studio workman (with extra emphasis on man, as Jessica Ritchey points out). Now, indie features act as showreels or auditions, with people speculating over which directors will get hurled into the maw of the next big-budget property. And by putting the emphasis on this, it pushes the truly independent American filmmakers working today—the Andrew Bujalskis, the Josephine Deckers, the Rick Alversons, the Alex Ross Perrys, the Sean Bakers, the Nathan Silvers, and the Matthew Porterfields, to name a few—even further into the fringe. People look at the trajectories of people like Trevorrow, Edwards, Johnson, Webb, Gunn and others as a sign of indie taking over the mainstream, but it’s more like the mainstream assimilating the indie universe. The pockets of Hollywood studios may be getting bigger, but the opportunity for discovering and supporting groundbreaking new talents appears to be getting smaller with every year.