Batman, Robin Hood and the Death of Classical Heroism

The myth—or rather, the idea—of Robin Hood has resonated across the world since stories of him first emerged in the mid-17th century. His schtick is sublime in its simplicity: he robs from the rich, gives to the poor and has a lot of fun doing it. He’s a rabble-rouser, a deadly archer, a protector of justice and a smooth-talking ladies’ man. An all-around good dude. His brand of clean-cut heroism has gone out of fashion in recent times, however; these days, stand-up heroes like Robin Hood are treated like a joke. It’s a crying shame.

1938’s terrific, jaunty The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring an improbably chipper Errol Flynn, is playing on July 4th as a part of TIFF’s “Dreaming in Technicolor” film showcase. It’s a treasure that all should see, though it’s the kind of lighthearted hero’s tale mainstream audiences have sadly lost an appetite for.

We’ve grown too cynical and in love with mayhem and revisionism to take seriously a man in green tights swinging on vines and letting out a big “A-HA!” as he pushes his fists into his hips and puffs out his chest. Romantic swashbuckling is difficult, I’m afraid, for the average 2015 moviegoer to take un-ironically. Ridley Scott‘s 2010 Robin Hood ran in the opposite direction of the Flynn version, painting a dreary picture of 13th-century England for Russel Crowe‘s “Robin Longstride” to brood around in because, these days, gloom is all the rage.

Our generation’s Robin Hood, arguably, is the Dark Knight himself. Batman is the perfect example of the kind of hero people crave today: psychologically damaged, shrouded in darkness, defined by tragedy and loss. No superhero, not even the bright and shiny Marvel ones, can contend with his superpower-less, black-on-black hipness. His look has evolved over the years, getting scarier and scarier with each reboot of the movie franchise, to the point where the latest version of the Bat, played by Ben Affleck in the upcoming Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, straight-up looks like evil incarnate. We’ve come a long way from Robin of Loxley and his funny little hat.

In The Adventures of Robin Hood, directed by Michael Curtiz (and, to a lesser extent, William Keighley), we see Flynn’s Robin stride into the malevolent Prince John’s massive banquet hall, plopping down a (very illegally) poached royal deer in front of the interim king. Surrounded by an army of armed men, Robin accuses John of treason and vows to avenge the missing King Richard and fight for the poor. What courage! What honor! For centuries, this was the epitome of heroism.

Batman treats evil-doers a bit differently, to put it mildly. He’s an intimidator who lurks in the shadows and strikes fear in his enemies from behind a mask, a symbol that hides his true identity (as a billionaire, another subversion of the Robin Hood myth). He’ll do anything to gain an advantage (short of killing, of course). In a classic comic book version of the Batman/Superman confrontation (found in Jeph Loeb’s Hush), Bruce Wayne defines his true nature. “If Clark wanted to,” he says internally as Superman pulls his punches, “he could squish me into the cement.” He suddenly smashes Superman in the face with a ring made of kryptonite. But Superman’s got an even bigger weakness than the glowing green stone, as Bruce explains. “Deep down, Clark’s essentially a good person. And deep down, I am not.”

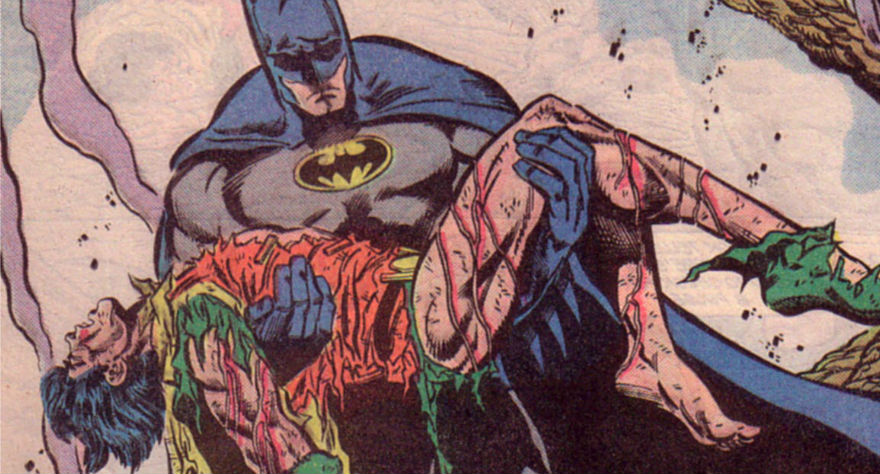

Where’d all the good guys go? A remnant of Robin Hood’s youthful spirit does exist prominently in Batman lore. His famous sidekick, Robin, was clearly inspired by Robin Hood. In fact, “The Boy Wonder” was a direct homage to Errol Flynn. Robin is the last glimmer of innocence in Bruce Wayne’s world, a playful young ally designed to bring a bit of levity to the Batman comic book series.

The character’s gruesome death is a darkly poetic sign of the times, now more than ever.

Jason Todd, the second to take up the “Robin” identity, is brutally beaten with a crowbar in front of his own mother (who’s just sold him out), his medieval yellow cape and green boots soaking in a puddle of his own blood. Mother and son are restrained, a ticking time bomb plunked beside them. Jason throws himself onto the bomb to shield his mom, despite her betrayal, in a final act of heroism. With Robin’s bright light snuffed out, only darkness remains for the mourning “caped crusader.” Written by Jim Starlin, the story was called “A Death in the Family.”

It’s an apt parable for what’s happened, culturally, to exuberant, grinning movie heroes like Flynn’s Robin Hood. Jason Todd was murdered by The Joker, a demented cackler with a sick sense of humor who applauds and giggles at the sight of brutality and pain. Sound like anyone you know? If Robin represents Robin Hood’s chivalric valor, the Joker symbolizes modern audience’s regurgitation of such classical ideals. He’s more interested in Batman; they’re a reflection of one another, both messed-up social outliers with a penchant for violence. “I don’t wanna kill you,” Joker tells Batman in Christopher Nolan‘s The Dark Knight. “What would I do without you?”

As moviegoers, we owe it to ourselves to not let pure, lighthearted heroics fall into extinction at the cinema. The reason Zack Snyder‘s The Man of Steel sucked was that it wasn’t any goddamn fun. It was a de-saturated, over-produced drag obsessed with mining darkness out of a character who should inspire wonder and make kids cheer. Batman v Superman looks to offer more of the same, depressing superhero action.

Get excited about The Adventures of Robin Hood instead. It’s everything The Man of Steel isn’t: fun, full of laughter, bursting with life (in Glorious Technicolor) and punctuated by thrilling, plain-spoken action sequences. If we would just let go of our snarky aversion to unclouded optimism every once in a while, perhaps Robin could live once again.