With her discomforting new psychological thriller Always Shine premiering as part of the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival, filmmaker Sophia Takal has already drawn comparisons to Brian De Palma, David Lynch, and even Ingmar Bergman with her new film. Yet, reviews of Always Shine that point to the film’s central pair of femme fatale-style blondes or the voyeuristic lens it applies to its actresses overlook a significant quality of Takal’s 2nd feature. “I don’t really know that there are a lot of movies about female friendships that ring true to me,” she begins during an early interview one morning in Midtown. “At least none that I’ve seen that I can think of right now.”

The tension in Always Shine is fueled by the mutual envy between its leads Anna (Mackenzie Davis) and Beth (Caitlin FitzGerald) best friends who decide to rebuild their broken bond by spending a weekend together in Big Sur. More than just spending time with one another, the trip is a chance for both actresses to escape how the outside world views them, as well as the roles—both personal and professional—in which they feel trapped. As the two old friends reconnect, their underlying resentment for one another turns their vacation into an anxiety nightmare with dangerous consequences.

In her sit-down interview with Way Too Indie during Tribeca, Always Shine director Sophia Takal discusses the competitive jealousy that inspired her film, the thematic importance of having female characters portray actresses, and how Always Shine helped the filmmaker come to terms with the competing aspects of her own personality.

Always Shine was written by your husband [screenwriter Lawrence Michael Levine, who also plays Jesse in the film], were you part of the initial development of this idea?

Sophia Takal: I came up with a tiny seed of the idea of wanting to make a movie about my own struggles with fitting into a normal idea of femininity. I made a movie called Green, and right after that movie came out something got triggered in me where I felt insanely competitive with all my friends—actor friends, director friends – and I was sabotaging those relationships. I was filled with all this rage and I was so angry.

I was taught that the right way to be a woman was to be shy and deferential—to not take up too much space—but I felt so big and bossy and aggressive and I just felt so bad about myself. It was creating this very violent conflict within me, and Larry was sort of just watching me unravel, go totally crazy and alienate everyone around me. We started talking a little bit about how I was feeling. I always gravitate toward making movies about really personal things.

I started talking to other women about saying “I really don’t feel like a woman, I don’t feel like I’m doing a good job at this,” and they would say “I don’t feel that way either.” I realized that it wasn’t just specific to me, but maybe there was a little bit more of a universal struggle that we were experiencing as women. So I wrote a one-page outline of ideas for how I could make it into a movie.

Larry really connected with these feelings. He had felt [competitive] towards me, [like] I was feeling towards other people. He had similar feelings about not fitting into the typical masculine roles of being really, really rich, and really, really powerful, and not emotional, and not crying. He said, “I felt a similar alienation from the set of expectations of my gender and I think that we could do something really interesting.” He’s an incredible writer, a much better writer than I am. So I just trusted him to create a script based on our shared set of experiences.

We did think it was important to address femininity rather than [make it] about a man. He read a lot of feminist books about female archetypes. There’s this one really great book called “Down From the Pedestal” [by Maxine Harris], which was all about different female archetypes and how women fit into them. He read books about celebrity obsession, “Fame Junkies” [by Jake Halpern] and “Gods Like Us” [by Ty Burr]. A lot about feminism and celebrity.

So that increased attention to your careers was a part of the inspiration, as well?

Definitely. Larry and I both got very career-obsessed. Just striving, grasping, not being satisfied with anything we had. Really feeling that our self-worth was bound up in this idea that we needed to become famous. And I feel like we just fell prey to what our society tells us, where celebrities are the new gods. It’s hard to feel valuable in a society that tells you that the most valuable people are these tall, beautiful men and women. It’s a bummer.

I was talking with Andrew Kevin Walker, who wrote Nerdland, about this desperation from the fringes of the entertainment industry. The tangible aspects of modern fame, I think, makes it seem not so out of grasp, which can drive you insane if you’re in that periphery.

Yeah. Also, because a lot of people are famous for no reason. The act of getting famous is a focus, rather than the act of creating and fame [coming] as a byproduct of that. It seems to have taken people over more and more. I talked with Mackenzie and Caitlin about that a lot. That when you become an actor you become an actor because you want to create something and enter this secret space where you’re connecting with someone. Then the weird by-product of being successful at that and getting to work is being pigeonholed into these tinier and tinier boxes.

[You] go to fashion shows and wear makeup and it’s not at all to do with why you started wanting to be an artist. A lot of business type people in the industry convince you that that’s essential in order to be an artist. Especially with actors. The less you know about an actor, the better the experience watching them work is going to be because you don’t have all the baggage. This internet age where you know everything about everyone is especially bad for everyone. Who’s someone really famous?

Ben Affleck.

Ben Affleck, yeah!

We spent a whole two years saying, “He doesn’t look like Batman.”

There’s just so much stuff, yeah. Like, “He had an affair with his baby sitter,” or whatever.

The femininity aspects in the film are really interesting, too. Particularly relating to the whole duality of these characters, balancing, “is this who I am?” with, “is this who I want to be?”

Definitely. To me, thematically, those are two sides of one woman. The process that I’ve undergone in my life is to synthesize those two aspects, rather than feeling pulled toward feeling small, getting angry that I wasn’t that way, and getting pulled in two directions. My personal journey has been to merge those two sides to become a more whole, balanced person. To not be mad at myself for not feeling one way, or reacting another way. They are two sides of the same person. And some people may naturally gravitate towards one. But both are kind of a performance.

There is that really interesting moment when you first introducing Mackenzie’s character and it’s made to look like an audition scene. Do you feel like that desire to be a certain type of person forces us to be performative in real life?

Yeah, I can only speak to my experience. But I feel like I’m performing all the time. Interacting with people is a negotiation. And I think as a woman, you’re taught how to perform to get what you need. Like, to seduce, or all these [prompts] that you could give to an actor at any time in a scene.

I think that was true, and that’s something we wanted to hone in on in the movie. And that’s why we used a lot of alienation and breaking of the fourth wall techniques, too, to remind people it’s not just actors who perform. It’s all of us who perform in our everyday lives and are choosing to present something to the world, [something] that’s been fed to us, rather than [present] who we really are.

To literalize some of that conflict by making them both actresses, was that something you debated at any point or was that there from the beginning?

It was always going to be actors in my mind. Mainly, because I started as an actor, so I really related to that. Then, a couple of producers and money people said, “Does it have to be actors? Because that’s not so accessible,” but I disagree. Birdman won an Oscar.

I always said, “No, it has to be actors.” I could never really articulate exactly why. And then this one filmmaker named Elisabeth Subrin has this really awesome blog called “Who Cares About Actresses?” And she articulates it so well, so I’m kind of just copying what she says. But it says that actresses represent to women what women are supposed to be. So when you choose how to portray a woman by picking an actress, you’re just telling women how to behave.

And then they become these archetypal figures.

Yeah, they’re just like tools to pigeonhole. I wanted to play around a lot with how actresses are used, which is why one thing I was excited about when I came onto it was obscuring the nudity. Almost showing them naked so that the audience would feel in their bodies that they wanted to see them naked and have to confront that feeling. Or obscuring the violence was another thing. I don’t know if this is the reaction people had, but it would be so cool if people were like, “Why can’t I see her kill her?!” and then get frustrated and say, “Why do I want to see her kill her?”

It’s that thing where you’re sort of seeking an answer that you already know. I found myself sitting there waiting to see a death scene but also knowing I didn’t need it. That’s a weird impulse.

Yeah, I just thought it might be interesting for people to sit with their desires rather than being given everything.

What were some of your visual influences? The quick splicing of scenes, the unsettling, disorienting style was really engaging and disorienting.

Mark Schwartzbard shot the movie and we watched Three Women like eight or nine times, and Images, the Robert Altman movie. We bought this 1960s zoom lens that was totally unused off of eBay, which was really cool. That was the only one we used for the whole movie.

Then Zach Clark edited it, and I had shown him a couple minutes of something that I had cut myself. I said, “I really want this to be weird and unsettling but I have no idea what to do.” Then he cut the opening credit sequence first and I was like, “Oh yeah, do that always, everywhere in the movie.” He kind of just brought the blinky, splicy stuff to me, and I thought it was amazing. He’s the one kind of responsible for more of the avant-garde elements. Seeing the slates – all those things – he added a whole other layer to the film. He really found visual ways to make it interesting.

A lot of what’s happening on-screen is not that unsettling or strange, but it’s the presentation of it – whether it’s the score or just that interstitching – that makes it so tense. Particularly, the scene where they’re running lines together.

Yeah, it’s so cool, they were really good!

Were you deliberately looking to make seemingly smaller moments play big?

Yes, definitely. My first movie, Green, I was also playing around with elements of genre, but it wasn’t as much of a genre movie. And this I really wanted to make it a psychological thriller, but I still wanted to root it in naturalism and [keep it] performance-driven. So all the choices we made with shooting was to make it as scary as possible

Same with music and editing. And I got really lucky with the actors because I love single-take scenes and they were so talented that we didn’t need to cut a performance. They were just able to do it on set. Not cutting away in certain tense moments built more tension, so I was really glad to be able to have that.

How did Mackenzie and Caitlin get involved? Did you seek them out?

They both came to me through agents and casting directors in the more traditional way. We cast Mackenzie first, and she just really understood Anna, understood the script. I was really excited and I was a huge fan of her work. Caitlin’s agent reached out to me, I was also a huge fan of her work. They were the two women that I spoke to that totally understood the script backwards and forwards, and had clear, specific ideas for their characters.

For me, as the director, casting is essential. Part of the way I decide to cast someone, I choose the person who I think is going to need the least amount of help. For everyone in the cast and crew, I just want everyone who can do their job so I stay out of the way. That’s a big part of what I was looking for. People who really understand this material, people who were willing to come out with me into the woods, work with a really small crew, do the weird hippy new-agey warm-ups I insist on doing and the meditation. People who feel that this is an important movie to make with important themes. Not just people who say “Oh I get to have the lead in an indie.” There was a lot of trust between the three of us that really moved me. It was really exciting and cool. It was the first time I worked with actresses that I didn’t have a relationship with before.

I was wondering if at any point you had considered casting either of them in the opposite role.

No.

It was clear from the start?

It was clear from the start. Yeah.

You’re a multi-hyphenate, actress being one of them. Was there any point where you thought you might be in this film?

At the very beginning when I gave Larry that one page I was like, “let’s just go into Big Sur and improvise a movie.” And he was like, “No, this could be better than that,” And I said, “I’m only going to give up my part if I find someone who I think can do a better job than me.” Then I did. And the role is so intense and aggressive that in order to inhabit that space I would be a terribly mean director.

The process was really important to me. Not knowing what was going to happen to a tiny independent film, I just focused on making sure that making this movie was as fulfilling as possible for everyone involved and that we learn and grow as a group and as individuals through this one month. So I thought that I could facilitate this kind of energetic whatever by being just a director. And it was so much easier than acting and directing. I acted in my first movie. Part of what’s fun about acting is losing yourself in the moment, but if you’re directing too, you can’t.

So you prefer to focus your energy in that way?

I think I do now.

Are you planning any other projects now?

Yeah, I have a script ready, but still not really big. But it’s more of a light dramedy. It will be an interesting shift to move away from these genre elements and focus more on like real life. I definitely don’t want to get pigeonholed as a genre director. Someone talked to me after the movie and said, “There are so few female genre directors, you could really make a big career out of it, do studio stuff,” and I was like, “Uh, I don’t know.”

That to me seems weird, I don’t like genre movies more than any other movies. For me, the through-line with all my ideas is that I’m talking about issues that women have that they’re maybe ashamed to acknowledge publicly. It can spark a dialogue and make them feel less alone, and I don’t think it needs to be any particular genre to do that.

One of the very interesting things about Always Shine is that it does talk about jealousy between friends in a way people tend to not acknowledge or not want to acknowledge, at least. Have you thought about why it’s so difficult to confront?

Do you have that feeling with other male friends?

I think I do. For me, it’s about relative positions in life. And certain people get, like, a nice apartment, or a nice promotion. It’s like a milestone type of thing.

Yeah, I guess I could go deep into an anti-capitalism rant right now. I think it’s the nature of capitalism to have a scarcity mentality and to feel like there’s not enough to go around for everyone. I think that’s particularly true about actresses. That’s another reason I think it’s a cool career to give these two characters. There’s one part and one person can get it.

And it’s not necessarily about talent or anything.

Yeah, I really think that’s true for everyone, I think that that’s a big problem with this society’s obsession with money and power.

It’s an unflattering obsession to have.

Yeah, and then it’s embarrassing. The reason I asked you about men was because with women there’s a huge emphasis on perfection and quietness and not challenging, and so that’s why I was wondering if that was why we don’t like to talk about it, but I don’t know. If everyone feels that way then I don’t know what it is.

Maybe it is just the sense of acknowledging that you don’t feel good enough or you haven’t accomplished enough.

Right. Because everyone’s performing, so you want to create this image of success or having it all together and not being jealous. But then it’s eating away at you inside, making you go crazy, and all of the sudden you’re screaming and crying in the post office. Just like, “Why can’t you give me my package without an ID?!” That didn’t actually happen.

It’s a metaphorical post office.

But I did really shove my boyfriend’s manager because he called me a primadonna. So [the movie’s] based on real life.

Transcription assistance from Jason Gong

]]>

'It's only after we've lost everything that we're free to do anything.'

]]>

'It's only after we've lost everything that we're free to do anything.'

]]>

In large part, what made Joe and Andrew Russo’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier such a successful and somewhat transcendent superhero movie was that its going concern wasn’t a global or even galactic catastrophe, but a personal one. The friendship between Brooklyn bros Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) and James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes (Sebastian Stan) threatened […]]]>

In large part, what made Joe and Andrew Russo’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier such a successful and somewhat transcendent superhero movie was that its going concern wasn’t a global or even galactic catastrophe, but a personal one. The friendship between Brooklyn bros Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) and James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes (Sebastian Stan) threatened […]]]> 'Ukrainian Sheriffs' can't meet the challenge to make its own subject matter interesting.]]>

'Ukrainian Sheriffs' can't meet the challenge to make its own subject matter interesting.]]> This found-footage doc about one family's addiction to materialism is impossible to believe but impossible to resist.]]>

This found-footage doc about one family's addiction to materialism is impossible to believe but impossible to resist.]]> 'Sonita' follows the beats of a traditional success story, but its director's self-interests threaten to overpower the entire film.]]>

'Sonita' follows the beats of a traditional success story, but its director's self-interests threaten to overpower the entire film.]]> Penny Lane's documentary 'NUTS!' is deceitful for all the wrong reasons.]]>

Penny Lane's documentary 'NUTS!' is deceitful for all the wrong reasons.]]> This sluggish documentary about Finnish cheerleaders suffers from a flat presentation.]]>

This sluggish documentary about Finnish cheerleaders suffers from a flat presentation.]]> A pinball wizard tries to overcome personal hurdles in this one-sided documentary. ]]>

A pinball wizard tries to overcome personal hurdles in this one-sided documentary. ]]> If you're looking for something to stream this weekend, in particular four very different documentaries, check out this week's streaming recommendations.]]>

If you're looking for something to stream this weekend, in particular four very different documentaries, check out this week's streaming recommendations.]]>

Fantasy and reality blur on multiple levels in this uneven arthouse film posing as a documentary.]]>

Fantasy and reality blur on multiple levels in this uneven arthouse film posing as a documentary.]]> A serial impersonator of subway workers is documented in this compelling portrait of institutional neglect.]]>

A serial impersonator of subway workers is documented in this compelling portrait of institutional neglect.]]> There's a story to be told about the golden age of burlesque. This film isn't that story.]]>

There's a story to be told about the golden age of burlesque. This film isn't that story.]]> One reporter's curiosity about a strange internet video leads to a series of unbelievable discoveries in this engrossing documentary.]]>

One reporter's curiosity about a strange internet video leads to a series of unbelievable discoveries in this engrossing documentary.]]> A lyrical ode to a First Nations tribe and the land they call home.]]>

A lyrical ode to a First Nations tribe and the land they call home.]]> 'My Blind Brother' is mostly amusing and its performances are strong, however, the tone remains unwavering until the film’s ending: lightly comedic, but unrelentingly self-serious.]]>

'My Blind Brother' is mostly amusing and its performances are strong, however, the tone remains unwavering until the film’s ending: lightly comedic, but unrelentingly self-serious.]]> History, journalism, and storytelling converge in a marvelous doc that heralds the most unappreciated section of the newspaper.]]>

History, journalism, and storytelling converge in a marvelous doc that heralds the most unappreciated section of the newspaper.]]> 30 years ago Crimewave made its disastrous bow at the box office. Has the past three decades been any kinder to Raimi's slapstick stinker featuring a script by the Coen Brothers?

]]>

30 years ago Crimewave made its disastrous bow at the box office. Has the past three decades been any kinder to Raimi's slapstick stinker featuring a script by the Coen Brothers?

]]>

A lo-fi romantic comedy with a New York sense of humor and a tremendous supporting cast.]]>

A lo-fi romantic comedy with a New York sense of humor and a tremendous supporting cast.]]> Jia Zhangke explores the human condition in 'Mountains May Depart' with a masterful performance from Zhao Tao.]]>

Jia Zhangke explores the human condition in 'Mountains May Depart' with a masterful performance from Zhao Tao.]]>

"That's why we used a lot of alienation and breaking of the fourth wall techniques, too, to remind people it's not just actors who perform. It's all of us who perform in our everyday lives and are choosing to present something to the world, [something] that's been fed to us, rather than [present] who we really are."]]>

"That's why we used a lot of alienation and breaking of the fourth wall techniques, too, to remind people it's not just actors who perform. It's all of us who perform in our everyday lives and are choosing to present something to the world, [something] that's been fed to us, rather than [present] who we really are."]]>

Director Justin Webster talks about getting access to world-renowned superstars like David Villa and Frank Lampard and the challenge of vérité-style documentary filmmaking.]]>

Director Justin Webster talks about getting access to world-renowned superstars like David Villa and Frank Lampard and the challenge of vérité-style documentary filmmaking.]]> Sharon Horgan discusses the advantage television has when developing romantic comedies and the importance of making a show that was more than just gags.]]>

Sharon Horgan discusses the advantage television has when developing romantic comedies and the importance of making a show that was more than just gags.]]> Rafael Palacio Illingworth discusses the real-life spat that inspired the movie, what types of questions he peppered the actors with prior to casting, and more.]]>

Rafael Palacio Illingworth discusses the real-life spat that inspired the movie, what types of questions he peppered the actors with prior to casting, and more.]]> Green Room is sure to go down as the most overwhelmingly intense movie of 2016, and unless another filmmaker can match Jeremy Saulnier’s knack for suspense, violence, and pulling the rawest performances out of his actors possible, it’ll reign as genre-movie king for a good long while. Starring Anton Yelchin, Imogen Poots, Alia Shawkat, Blue Ruin‘s Macon Blair, and […]]]>

Green Room is sure to go down as the most overwhelmingly intense movie of 2016, and unless another filmmaker can match Jeremy Saulnier’s knack for suspense, violence, and pulling the rawest performances out of his actors possible, it’ll reign as genre-movie king for a good long while. Starring Anton Yelchin, Imogen Poots, Alia Shawkat, Blue Ruin‘s Macon Blair, and […]]]>

A mockumentary about a world where men no longer have a purpose is entertaining, even when it's uneven.]]>

A mockumentary about a world where men no longer have a purpose is entertaining, even when it's uneven.]]> Andrew Kevin Walker and Chris Prynoski discuss Nerdland's nihilistic vision of modern society and their shared appreciation for improv in moderation.]]>

Andrew Kevin Walker and Chris Prynoski discuss Nerdland's nihilistic vision of modern society and their shared appreciation for improv in moderation.]]> We interview Lindsay Burdge and Arthur Martinez, stars of the experimental film 'Actor Martinez.']]>

We interview Lindsay Burdge and Arthur Martinez, stars of the experimental film 'Actor Martinez.']]>

A strong ensemble cast helps offset the copycat nature of this psychological thriller.]]>

A strong ensemble cast helps offset the copycat nature of this psychological thriller.]]> Patton Oswalt and Paul Rudd voice an inept pair of Hollywood star wannabees that get in over their heads on an all-out quest for fame.]]>

Patton Oswalt and Paul Rudd voice an inept pair of Hollywood star wannabees that get in over their heads on an all-out quest for fame.]]> A spectacular coming-of-age adventure with digital artistry to die for.]]>

A spectacular coming-of-age adventure with digital artistry to die for.]]> Sold, an adaptation of the Patricia McCormick novel of the same name, follows a Nepalese girl named Lakshmi (Niyar Saikia) who falls into a world of sex trafficking and abuse when she travels to India. She’s imprisoned in a brothel called Happiness House with several other children, watched over by their tyrannical brothel madam (Susmita […]]]>

Sold, an adaptation of the Patricia McCormick novel of the same name, follows a Nepalese girl named Lakshmi (Niyar Saikia) who falls into a world of sex trafficking and abuse when she travels to India. She’s imprisoned in a brothel called Happiness House with several other children, watched over by their tyrannical brothel madam (Susmita […]]]>

This doc about people living on society's fringe offers little beyond its gorgeous visuals.]]>

This doc about people living on society's fringe offers little beyond its gorgeous visuals.]]> The Measure Of A Man is one of the most depressing films of the year, featuring a brilliant performance by Vincent Lindon.]]>

The Measure Of A Man is one of the most depressing films of the year, featuring a brilliant performance by Vincent Lindon.]]> An interview with Andrew Cividino on his lauded directorial debut 'Sleeping Giant.']]>

An interview with Andrew Cividino on his lauded directorial debut 'Sleeping Giant.']]> It's a stunning lineup this week on the Way Too Indiecast as Loki himself, Tom Hiddleston, joins the show along with director Marc Abraham to talk about their new movie I Saw the Light, based on the final years of country music icon Hank Williams' life. Mr. Hiddleston also talks about working with Elizabeth Olsen, learning to sing with country legends, and his take on irascible MCU fans.

]]>

It's a stunning lineup this week on the Way Too Indiecast as Loki himself, Tom Hiddleston, joins the show along with director Marc Abraham to talk about their new movie I Saw the Light, based on the final years of country music icon Hank Williams' life. Mr. Hiddleston also talks about working with Elizabeth Olsen, learning to sing with country legends, and his take on irascible MCU fans.

]]> Director Marc Abraham takes a unique approach to the musician biopic with I Saw the Light, a movie spanning the six music-filled, final years of Hank Williams’ life. Intertwining the country icon’s songs with his turbulent life experiences (revolving largely around his wife, Audrey, played by Elizabeth Olsen), the film focuses not on Williams’ artistry, but […]]]>

Director Marc Abraham takes a unique approach to the musician biopic with I Saw the Light, a movie spanning the six music-filled, final years of Hank Williams’ life. Intertwining the country icon’s songs with his turbulent life experiences (revolving largely around his wife, Audrey, played by Elizabeth Olsen), the film focuses not on Williams’ artistry, but […]]]>

A wrenching and intimate tale about the criticality of communication, and the collateral damage of deceit, in the wake of loss.]]>

A wrenching and intimate tale about the criticality of communication, and the collateral damage of deceit, in the wake of loss.]]> A solid studio comedy and star-vehicle for the ever-entertaining McCarthy.]]>

A solid studio comedy and star-vehicle for the ever-entertaining McCarthy.]]> A strong dose of home invasion films are available to stream this weekend!]]>

A strong dose of home invasion films are available to stream this weekend!]]>

A well-oiled machine of a hangout movie from Richard Linklater.]]>

A well-oiled machine of a hangout movie from Richard Linklater.]]> A surprisingly uplifting film considering the harrowing subject matter of children being killed in Ethiopia.]]>

A surprisingly uplifting film considering the harrowing subject matter of children being killed in Ethiopia.]]> We talk to Mike Flanagan and Kate Siegel about their horror film 'Hush.']]>

We talk to Mike Flanagan and Kate Siegel about their horror film 'Hush.']]> Writer/director Gabriel Mascaro talks about his latest feature 'Neon Bull.']]>

Writer/director Gabriel Mascaro talks about his latest feature 'Neon Bull.']]> A man uses a father/daughter road trip to flee his debts and his demons in this uneven but effective drama.]]>

A man uses a father/daughter road trip to flee his debts and his demons in this uneven but effective drama.]]> History is made behind the camera in this detached documentary about the world's first citizen journalists.]]>

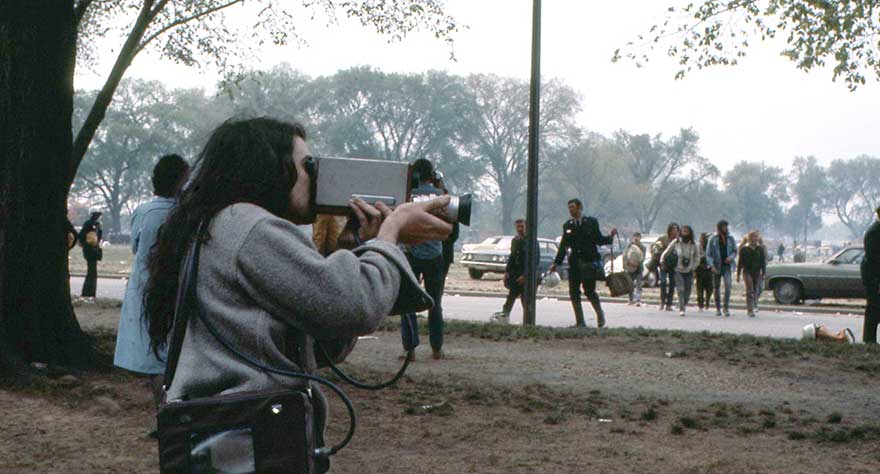

History is made behind the camera in this detached documentary about the world's first citizen journalists.]]> A case study in indulgent and privileged grieving.]]>

A case study in indulgent and privileged grieving.]]> In one of the biggest, baddest episodes of the Way Too Indiecast yet, we welcome two of the best directors in the game as we hear from Richard Linklater about his '80s college hangout movie Everybody Wants Some!! and are joined by Jeff Nichols, whose sci-fi thriller Midnight Special hits theaters this weekend as well.]]>

In one of the biggest, baddest episodes of the Way Too Indiecast yet, we welcome two of the best directors in the game as we hear from Richard Linklater about his '80s college hangout movie Everybody Wants Some!! and are joined by Jeff Nichols, whose sci-fi thriller Midnight Special hits theaters this weekend as well.]]> One of the all-time greatest films, Bicycle Thieves is on-demand this weekend, plus some other classic movies available on various streaming platforms.]]>

One of the all-time greatest films, Bicycle Thieves is on-demand this weekend, plus some other classic movies available on various streaming platforms.]]>

Like his 2011 film Take Shelter, Jeff Nichols‘ Midnight Special was born out of fear, specifically the fear of losing his son. “I think, really, we’re terrified of losing them, so we’re going to try to figure out who they are to try to help them. Help them become the ones who manifest their own destiny,” […]]]>

Like his 2011 film Take Shelter, Jeff Nichols‘ Midnight Special was born out of fear, specifically the fear of losing his son. “I think, really, we’re terrified of losing them, so we’re going to try to figure out who they are to try to help them. Help them become the ones who manifest their own destiny,” […]]]>